Roving packs of five-year olds roam the overgrown lots by the abandoned steel mills. Baxter sees them when driving home through Buffalo at night, the sun setting pretty red in the pink sky. Regulations require that residents padlock their trashcans, but there are loopholes in the law, or perhaps citizens who do not abide by these laws because there seems no shortage of kids upending trashcans, kids crawling inside dumpsters, kids puncturing the industrial strength green plastic trash bags in search of chicken carcasses and potato peelings. Baxter has seen the children, dressed in tee shirts and cotton shorts, suck out the marrow from drumsticks and scoop out the pulpy remains of grapefruit halves that some health-crazed citizens have been squeezing for their juices. He is amazed at kids’ resourcefulness, how they crack open acorns to chew on the nuts, how efficient they are in plucking the yellow dandelion flowers and eating them before they go to seed, for there are vast sections of town where one never sees the dandelion’s white puffs in the grassy seas, where one never spies their seeds floating in the breeze.

On Tuesday night, Baxter selects two dozen cookies from the bakery across his office. The cookies are heart-shaped, decorated with red glazes and sprinkled with nonpareils and powdered sugar. At a buck fifty a pop, the bill with tax is just under forty dollars. He and Chapelle have been having problems lately, arguing really, about whether to have another child. Things with their first children, fraternal twins, didn’t turn out as Baxter had wanted and he is reluctant to put himself through that kind of agony again, though it tears him apart to come home most nights to hear his wife tell him what a good mother she was to the boys. Driving home with the cookies resting in a ribbon-tied box in the passenger seat, the car is warmed with the competing aromas of chocolate chip, peanut butter, and anise. The first frost of the season is expected in the evening. Baxter is tempted to break into the box himself.

He’s listening to the classic rock station, humming along to CSN&Y’s “Teach Your Children Well,” when one of the homeless kids chases a soccer ball into the intersection. The lights are changing. Baxter clutches his steering wheel and swerves hard left to avoid the child. The car screeches. His tires, which he has been meaning to replace with a set of Perrellis, are nearly threadbare and with the slick road conditions, he’s unable to steer the car out of a skid. The cookies topple off the seat and smash against the gearshift. The car slams into a curb. An airbag explodes out of the steering wheel, the scalding force of which knocks his head against the padded leather headrest at the back of his seat. Air curtains inflate at either side.

As his car’s horn goes off seemingly of its own accord, he’s thinking of Chapelle, his wife. He sees her as she was on the morning that she gave birth to their twin sons, drugged out in a pink cotton maternal gown that fastened with drawstrings, happy with a glazed look on her face, her face flushed with exhaustion, sweat on her brow, her red hair tied in pigtails to keep it out of her eyes. Until that moment when the second of the boys crowned, he had not realized precisely how much effort was involved in childbirth. He remembers the frantic urgency in which she squeezed his hand and feels remorse for his refusal to allow her another stab at motherhood.

The airbags deflate with a sudden slurp like the sound a child makes when eating spaghetti. Baxter is dazed and, though the car rests on an incline under a fizzling sodium arc lamp, the night seems immensely darker than he remembers. Dark birds, crows or ravens—Baxter could never tell the difference—are perching on the chain-link fence on the opposite side of the street. He rolls down the window and feels the cold air against his face and smells burnt rubber, which he recognizes as coming from his tires during the skid. The cookie box sits, upended, at his feet. Ripping open the box confirms what he fears: not a single one of the wafer-thin cookies survives intact. It is the law of finery: the more expensive an object, the more likely it is to fall apart under stress. A cheap bag of Keebler Grasshoppers could survive a head-on collision with a semi-trailer; of course, mere supermarket cookies (Look! They’re made by elves!) would not make much of an impression on Chapelle.

Baxter flings one of the broken cookies, the pointy end of a heart, out the window. The cookies are worthless. If he wasn’t allergic to roses, he’d stop off at a grocery store to buy flowers.

And then he hears it: the sharp thwap thwap thwap of a soccer ball being dribbled on the asphalt street. Looking into the rearview mirror, Baxter’s breath fogs the glass. His heart is still racing from the near accident. He cannot see whomever might be kicking the ball.

An errant touch sends the ball crashing into the fence and a blanket of black birds, cawing, takes off in flight directly over Baxter’s car.

The kid appears, the same dark-haired boy whom he had swerved to avoid. His black hair is a matted tangle, a leaf of some kind lodged just above his ear. He is so scrawny, the tails of his tee shirt blowing in the wind, that he barely would have left a scratch on the bumper. Something that looks like axle grease stains his forearm. A car alarm goes off in the distance, momentarily startling him.

The boy scoops up the cookie piece and is about to eat it when he sees Baxter looking at him. He holds the piece up, trembling, extending it as if to return it, but when Baxter nods, he tucks it into his mouth. Baxter throws out another cookie piece, a frosted ginger snap that cracks apart when it lands on the pavement and the boy gets on all fours and crawls on the streets, picking up the pieces that land in potholes and puddles.

Other children stealthily appear from behind bushes and the crevices between down-and-out brick apartment buildings. Baxter steps out of the car and is surrounded by a small crowd, the children mewing like kittens, some of them on all fours rubbing up against him, their backs arching against his knees.

The original boy bursts through this crowd. A light rain, sprinkles really, begins to fall, and when he breathes, Baxter can see his breath. He’s holding out his soccer ball, his mouth open, the baby teeth inside like fattened grains of rice, and Baxter’s first thought is that he’s being drafted into a game but then the boy nods at the cookie box in Baxter’s hands, which Baxter immediately sets on the street.

With so many kids, it is hard to imagine any one of them getting more than a couple of bites yet there is an orderliness to how the children approach the box. A line forms. One girl picks up a cookie that is as large as her hand and breaks it in three, eating the smallest piece, and returns the others to the box. Baxter worries that people, fellow citizens, may be watching from the surrounding apartment buildings, training binoculars upon him, but there is nothing he can do to prevent them from seeing what is happening. A boy takes his cookie across the street, where Baxter sees him feeding it to a smaller boy whose denim overalls bulge from a distended belly.

Afterwards, when the children are licking their fingertips with slender pink tongues, cleansing themselves, the original boy places the soccer ball at Baxter’s feet. There’s a smile on his face, a rosiness in his cheeks that even in the pale anorexic light of the street lamp appears healthy. Although the white insides of the box are picked bare of crumbs, the box itself is undamaged save for the tear on its lid that Baxter made himself.

“No,” Baxter says, picking up the ball. He tries to give it back to the boy but the boy does not take it despite repeated attempts. The ball is in a sorry state of semi-inflation, in need of a good hand pump and maybe a towel to remove the grime gathered between its stitched panels. Water-logged, it weighs more than expected and Baxter could not imagine kicking the thing around, at least not in his black wingtips that were polished that morning.

The boy jerks his head up. His nostrils flare, giving the impression of smelling something foul, though the only thing odd that Baxter smells is the wet ball in his hands, which oozes a scent not unlike the worms he gathered when he was younger from the puddles the morning after a hard rain.

The boy takes off running, his bare feet slapping the pavement. The other children follow him down the side street to where the old grain mills run along Lake Erie. A century ago, before President McKinley was assassinated, Buffalo billed itself as “The Biscuit Capital of the World”; even now, you can find the faded logos of American Wheat and the National Biscuit Co. on the brick exteriors of the vacant warehouses.

Seconds after they leave, Baxter hears a police siren. The soccer ball feels like some kind of criminal evidence in his hands. He feels frozen in place. The squad car turns the corner, its flashing red and blue lights descending upon him. Baxter tosses the ball into the car and wipes his hands on his pant legs, instantly regretting the dirt he tracks into the worsted wool fabric of his khaki slacks. The squad car, a rusting Ford Crown Victoria with what looks like a bullet hole in the passenger side window, pulls up beside him.

A lanky officer steps out of the car, clipboard in hand, and adjusts the brim of his uniform hat in a way that obscures his eyes. A dab of marshmallow-like fluff—shaving cream, Baxter guesses—touches the corner of his ear. This officer-presence hovers over Baxter for a moment. A pair of handcuffs is clipped to one of his belt loops, a .44 service revolver holstered to his hip. Opening his mouth, his teeth shine with the phosphorescent white brilliance that can only be achieved through cosmetic dentistry. “You’ve been feeding the children, right?”

The charge of feeding children carries a fine not to exceed ten thousand dollars and a minimum three-week prison sentence, an obligation that can be filled on successive weekends. Newspapers print the names and addresses of repeat offenders.

Baxter shakes his head. The empty cookie box is still on the street, inches from his foot. If he makes an attempt to kick it under his car, he risks calling attention to the evidence. He gulps. “Whatever makes you say that, officer?”

“Sergeant,” the officer says, grunting. He touches the brass nameplate pinned to his uniform. Sgt. O’Callahan. “We’ve had three reports in the last fifteen minutes of someone fitting your description feeding cookies to children.”

O’Callahan reads off the descriptions—each has physical discrepancies that can lead to a plausible deniability: in one, Baxter’s blue blazer is described as a trench coat, his black hair given as “rust.” Another places him two blocks further south on the street, to a point near where a railroad-crossing signal hasn’t worked in years. These are the inconsistencies that can cause someone to lose faith in their fellow citizens. Baxter wonders if it is ever possible in this world for two people to look at the same thing and come back with identical impressions. O’Callahan smiles. “All three of them, however, gave the same license plate number: yours.”

Baxter closes his eyes. He thinks about the weekends he’ll spend in the clink, unable to watch football games, the disappointment in Chapelle’s face when he is forced to admit that he is a child-feeder. “I won’t let it happen again, sir.”

O’Callahan writes up a citation, getting from Baxter his vital statistics, address, and cell phone number. With each piece of information he divulges, Baxter feels his shame lifting. It is true what the public service announcements say: confessing your crimes is the first step to rehabilitation; with truth there is freedom.

“It’s funny,” Baxter says. He is overcome with a giddiness erupting inside him, a deep diuretic urge to expel every detail of his crime from his system.

“No it’s not,” O’Callahan says.

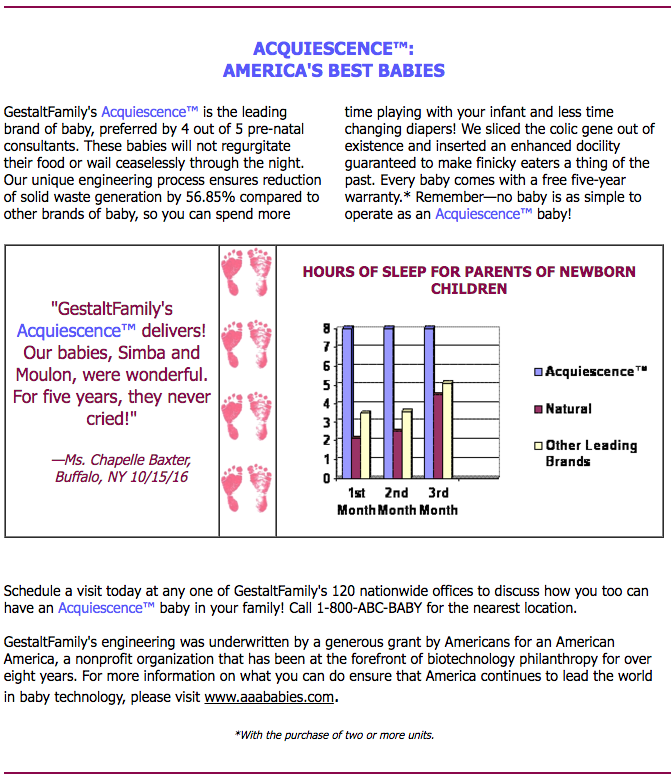

“I started feeding them by accident.” Baxter picks up the cookie box and tells O’Callahan how he bought the cookies as a peace offering for his wife, how they had been arguing about whether to have more Acquiescence children and how the roads glistened with a moist slickness when he saw a soccer ball and then one of the boys suddenly darted into the intersection, how there was something heroic wasn’t there about how he was able to steer into the skid avoiding both boy and serious damage to his car when traffic fatalities are one of the leading causes of death still and how pissed off—PISSED OFF—he was when despite everything the cookies still broke apart in such a way that he could never give them to his wife and how, when he tossed them out into the street, he was startled at how quickly the children swooped upon them and how honest injun he never thought before about feeding the children, but there you have it: an empty box of cookies.

O’Callahan tucks his pen behind his ear, displacing the dab of shaving cream. “It’s cute the way they meow nowadays, isn’t it? The children.”

“Yeah, I guess it is.”

A motorcyclist on a blue Harley zips through the street, slowing down as it passes the squad car, which still has its Christmas lights flashing. Disturbances, even one as non-confrontational as this, provoke curiosity. Across the street, people are opening their fogged second- and third-floor apartment windows, pointing at Baxter and the officer, no doubt reveling in the misdeed of their fellow citizen as proof that they themselves are clear of offense.

“Yesterday I arrested a retired grammar school teacher. She had gray hair down to here,” O’Callahan says, laying his gloved hand on his hip. He shakes his head. “She could have been my grandmother, except my grandmother’s dead. She had this cock-and-bull story that she was only scattering breadcrumbs in the park and expressed shock when I pointed out that children had been following her for a half-hour, eating everything.”

“Wow.”

“Wow is right. And they weren’t breadcrumbs. They were croutons.”

Baxter thinks about the salads that Chapelle makes from fresh mozzarella cheese, paper-thin slices of Bermuda onions, and a basil-flavored vinaigrette. She has been reading European cookbooks and experimenting with weird greens: maché, arugula, endives and an especially bitter radicchio. “I like croutons.”

“So does everyone else. Listen,” O’Callahan says. He kicks the pavement with the rubber heel of his boot. “You seem like a good guy. You ain’t going to feed the children anymore, are you?”

“No.” Baxter places his hand over his heart as if pledging allegiance to the flag. “Never more.”

O’Callahan holds the citation inches from Baxter’s nose and tears it in two, then four, then eight, taking some of the torn pieces and stripping them into ever smaller pieces. Baxter’s unclear what to make of this, the shreds blowing in his face. O’Callahan continues tearing apart what is left of the document until it is nothing more than fine white flakes disbursed by the wind.

“I’m not going to be arrested?”

“Today’s your lucky day.”

The mist, which had been falling, turns heavier. Baxter thinks he feels ice pellets plinking his cold cheeks. Getting back into his car, O’Callahan shuts off the flashing red and blue police lights and cranks the engine, filling the air with a sulfurous exhaust. There is something otherworldly about the corona of light that hovers around the street lamps.

Winter is the quietest season of the year, everyone bunkered in against the snowfall, their pantries stocked with canned stews, retorted foil pouches of tuna fish, coffee, and boxes and boxes of oatmeal and powdered soup mixes. Many of the children do not survive the first snow; those that do rarely make it to the final April thaw, engineered as they are with limited life spans and a profound aversion to the cold. Already, with the freezing rain clicking on the sidewalk, Baxter wonders if he stockpiled enough propane for the camping stove that he and his wife keep for when the electricity gives out.

Inside his car, hot air blasting out the heater vents, Baxter rubs his hands together to recover some sense of feeling. He still can’t pinpoint exactly what he might have said or done to deserve O’Callahan’s kindness. By all means, he should be looking at a jail term but instead he is free to roam the streets, free to go home and build a fire in his fireplace.

Before he drives away, Baxter picks up the soccer ball sitting in the back seat and goes outside. It’s been a long time since he last played the game and he’s tempted to give it a kick but, crossing the street, he slips on the ice and the ball careens out of his hands. The ball rolls down the hill and it takes Baxter several minutes to find it. His wingtips are not the best footwear to navigate the icy streets. Walking back up, he clutches the parking meters to avoid falling. He sets the ball on a bench set between two trees at the side of the road, in a place where he hopes it can be easily found.

II.

III.

The babies, Simba and Moulon, slept in cardboard boxes in the basement. They were the perfect babies. Sometimes Baxter and Chapelle wouldn’t see them for days but when the urge struck, they’d run down the basement stairs and play peek-a-boo and go off to the playground. Moulon climbed the ladders to the tallest slides, bounding up the steps two at a time, but refused to go down the slides when he got to the top. Instead, he’d sit on that toppermost step, helpless, his tangle of black hair swarming around him when the wind gusted, and stare down upon Baxter and Chapelle until one of them ran to fetch him. Simba loved sandboxes and would sit in them for hours, transfixed by the feel of sand slipping through his fingers.

Baxter drove his family afterwards to The Dutch Haus, an ice-cream parlour of antiquated design where teenage soda jerks still used chrome-plated machines to mix milkshakes. Waitresses wore their hair in complicated French braids and jotted down customer orders on little pink notepads that were shaped like ice cream cones. The place smelled of a wholesome goodness that only hot fudge sundaes could provide. Chapelle, a redhead whose dark green eyes Baxter still enjoyed staring into, only ever ordered lemonade because she was afraid of melted ice cream dripping down onto her cashmere sweaters. It was at moments like these, giggling at the way their boys lapped ice cream from their dishes, that Baxter felt closest to his wife.

The Acquiescence™ process was as easy as Chapelle claimed. The GestaltFamily offices were between a discount fine china outlet and a convenience store in a strip mall not far from where the last remaining drive-in movie theater in the region used to be. On the morning that they went there, Baxter saw that the first crocuses of the season, purple with a ribbon of yellow on each petal, had sprung up in the melting snows on either side of the cobblestone walk that led to their brick colonial. Spring was in the air and he was eager to see how the lilac bushes that he planted the previous fall in the back yard had survived the winter.

At GestaltFamily, a receptionist ushered Baxter into an EnhancementSuite, a dimly lit room with maroon wallpaper where some kind of sound system played environmental recordings—tweeting songbirds against the soft gestational rumbles of ocean surf. The principle feature of this room, a queen-sized bed, looked with its scrollwork of Arabesque symbols on the headboard, swirling hand-carved wooden posts, and opulent damask sheets and pillow coverings as if it had been airlifted from some fantastical Turkish palace. A hammered silver tray on the nightstand displayed a selection of suggestive magazines.

“Would you like soft jazz instead?” the receptionist asked, motioning to a bank of recessed audio speakers in the back wall. She was young, perhaps college age, and she twirled a strand of her hair as she spoke. Her attire was tasteful: olive culottes, a white knit top, leather sandals with intricately woven straps, and an ankle bracelet fashioned out of gold wire. “We could change it.”

“No, that’s all right.”

“Good,” she said. A new sound entered the seaside mix, eerie, perhaps the whistle of humpback whales but Baxter wasn’t sure, never having spent much time at sea. She handed him a shallow, thin-lipped glass plate. “Ejaculate into the Petri dish.”

She spoke in a disarming way, again twirling her auburn hair, her diction accenting the consonants with a directness that wavered between a command and a suggestion. Baxter considered the hundreds of men she must have helped in this situation, which, after all, was nothing more than a medical necessity.

Looking away, he unfastened his belt.

She shrieked. “Not in front of me!”

“I thought—”

“I know what you must have thought.” She crossed her arms and glared at Baxter, making him feel even stupider. The receptionist huffed. “Wait until I’m gone before you start messing with yourself.”

Baxter sat himself on the bed, which was so high that his feet dangled an inch from the floor. Chapelle was in the next room being sedated so that Copulation Technicians could extract an egg. The receptionist had slammed the door upon leaving, a crash that still reverberated in Baxter’s head. He feared that she would rush off and tell everyone, Chapelle included, about his faux pas.

It took him a long time to accomplish his task. He flipped through a couple of the magazines but it was no use. He thought of her—the receptionist—instead of his wife but each time he was close, each time he imagined unraveling her auburn chignon, he saw her crossing her arms again and frowning at his pathetic attempts. The bed was the softest, most luxurious he had ever sank into and he wondered what kind of man he was, unable to partake in the simple act of procreation.

Ten minutes later, there was a knock on the door. “Are you done in there yet?”

Baxter looked at himself, embarrassed at his semi-flaccid state. In a misguided attempt to create a sense of physical immediacy, the sheets were tangled around his knees. As if the sheets, as plush as they might be, could take the place of a lover’s thighs. “Nope.”

The door creaked open an inch. “Listen, I’m sorry I was rude to you. Please don’t tell my boss.”

Baxter shifted on the bed, trying to hide himself. “Okay.”

“Thank you,” she said. “I really need this job.”

An interminably long interval followed. Baxter wasn’t sure whether she was observing him or maybe had even walked away forgetting to close the door. He wasn’t about to get off the bed to close the door himself. “Could you shut the door? Please?”

“Thank you,” she said again as the door closed.

Later, holding hands with Chapelle, Baxter was ushered into the gallery of a glass-enclosed laboratory. Chapelle was still groggy from the sedatives and laid her head on his shoulder. They watched the technicians whip semen and egg together in high-speed centrifuges.

“I feel all warm inside,” Chapelle said.

They put on cardboard glasses with flimsy plastic lenses, the same kind that they might be given for a 3-D movie at an IMAX theater. Nothing could have prepared them for the entertainment aspect of the event. Chapelle brought her hand close to her face and wriggled her fingers, giggling, and Baxter had to admit the whole thing was kind of neat. Then the laboratory lights suddenly went dark and a series of lasers and infrared beams were shot at the mixture and, because she opted for natural childbirth, Chapelle was gently eased into a wheelchair, re-sedated, and rolled back into the CopulationChamber so that the mixture could be injected into her.

For nine months Chapelle and Baxter purchased baby toys and boasted to friends about due dates, ultrasound tests, and morning sickness. The idea was to enjoy five years of uncomplicated parenthood, dressing infants up in navy blue sailor suits and fetching compliments about their cute, well-behaved children while conspicuously strolling through shopping malls in the never-ending quest to find the perfect Teddy bear. It would still be possible in those golden years to live a carefree life without having to radically restructure social schedules to accommodate soccer practices, piano lessons, and grade-school sleepovers. As soon as her belly began to protrude, Chapelle took to wearing maternity outfits in Day-Glo variations on the color green. Declining cocktails at dinner parties, she tapped her belly. “I’m preggy. Can’t you tell from the healthy glow on my face?”

Simba and Moulon, as promised, had the identical manageable birth weight of seven pounds three ounces. Baxter and Chapelle cradled the twins in their arms as if they were precious footballs, the babies’ heads still pointy from their passage through the birth canal. Despite all the books they read, nothing could have prepared the new parents for the softness of a baby’s skin, their fresh talcum warmth, the glassiness of their eyes. The newborns’ sense of suckle was great, amazing Baxter each time they latched their lips around his pinkie finger, the ridged upper plate of their mouth soft and seemingly malleable.

They began walking at thirteen weeks and were potty trained by six months. Simba had a tiny pink sore on his chin that never healed from the day he was born. Baxter rubbed A&D Ointment on it from time to time. Whenever it was close to healing completely, Simba picked at the scab, causing a fresh trickle of blood to pulse from the sore.

“βeta versions,” GestaltFamily said when Baxter got them on the phone. “You can expect such things. It said so in the contract.”

One day, Baxter checked out a Dr. Seuss book from the library. It was a week before the boys’ fifth birthday and he and Chapelle were trying to figure out what to do about the boys’ future. Baxter stepped down into the basement with the book. The light bulb had burnt out, so he lit a candle. The boys were playing with a ball of yarn, swatting it with their hands, rolling it back and forth between themselves. He showed them the book and flipped through the pages, expecting if nothing else that the whimsical illustrations would hold their interest. They kept playing with the yarn. He pointed to the walls, where the candle cast shadows over the cinderblocks. Potato bugs, dead, rolled up like pellets, lay along the base of the wall and he made a mental note that he ought to sweep the floor.

“Look,” Baxter said. He moved his hands near the flickering flame and manipulated his fingers so that a figure similar to a unicorn appeared on the wall. Then he made an elephant and the Playboy bunny.

Simba screamed. Baxter looked down and he saw Moulon with two fingers in Simba’s mouth, trying to pry it open and force-feed him a potato bug.

“It’s time for bed,” Baxter said.

The boys scurried into their boxes, which Chapelle had re-filled the day before with absorbent pine shavings. Simba picked at a festering scab on his chin. He yowled. Moulon knelt on his knees and scratched behind his ear with his elbow. Baxter started to read but they showed no interest in the story, which was about a mischievous cat who wore a remarkable hat. Each time he re-read the first page, Simba yowled. Finally, Baxter put down the book, blew out the candle, and went upstairs.

The next morning, Baxter went downstairs to check on his sons. The boys were sitting together on the beat-up sofa. Sunlight cascaded down upon them from the casement windows, the Dr. Seuss balancing on their knees. Baxter sat on the stairs. Normally adroit at sensing the presence of others, the boys took turns flipping the pages, laughing and pointing at The Cat in the Hat and his two helpers, Thing One and Thing Two.

Moulon turned one of the pages but Simba turned it back, emphatically placing his index finger on a line of text. He dragged his finger slowly over the words, then pointed to Thing Two, who was running about flying a kite in a very messy house. Moulon mewed, prompting Simba to flip the page.

Baxter ran upstairs. The boys’ language skills had not progressed beyond baby talk and rarely had their intellectual curiosity extended beyond the desire to watch the same purple dinosaur DVD over and over and over.

Chapelle was in the kitchen, which smelled of grapefruit. She had been using the juicer, the one expensive gadget in their home that was used with any regularity. Grapefruit halves were stacked in the sink, pulped. She had once tried to run them through the garbage disposal, clogging the sink; because of the fuss he made, it was now understood that he would personally dump them in the trash outside to avoid further mishaps.

The quick steps up from the basement made Baxter feel more winded than he thought possible. He put his hand on his chest and felt his heart thump. “I think they’re learning how to read.”

Chapelle put down a Spanish travel book. Her red hair framed the corners of her face like drapery, hiding the corners of her eyes. Her pale skin always reminded him of peeled garlic cloves. She had been lobbying for a European vacation for many months, something of a reward to herself for being such a good mother. “Improbable.”

“I’m serious.” Baxter pulled up a chair next to Chapelle and patted the knee of her houndstooth skirt. Against her black cashmere sweater, the strand of freshwater pearls he had given her for her birthday looked like lustrous molten drops. He told her about the book, how Simba was scanning the words. Across the border in Fort Erie, an Ontario town otherwise known for its many Chinese restaurants, experimental clinics were trying to reverse the effects of GestaltFamily engineering with a variety of intravenous isotopic therapies and gluten-free diets, crazy really and nothing was guaranteed, Baxter admitted. One of the K–5 academies for the autistic now enrolled Acquiescence children. “They’ve had some luck—some of those children are actually talking.”

“Baxter, what are you saying? Have you any idea how much private schools cost nowadays?”

Baxter shrugged. The answer seemed superfluous. He pictured having conversations with his boys and the eventual joy of teaching them how to rebuild car engines in their teenage years, all of them with grease on their hands and the smell of auto oil in their hair after a long afternoon in the garage tinkering with crankshafts and fuel injectors.

“Sixteen thousand dollars a year. For kindergarten. Times two. Times every year for however long they might live.” The numbers struck Baxter like an algorithmic bomblet. Chapelle knew people who knew people who knew people who were in the same boat. Simba and Moulon had the potential to bankrupt them. Health insurance policies didn’t normally cover experimental treatments or pick up the costs for the additional speech and occupational therapies that were needed if their children were to be successfully reconditioned. The costs were enormous. “And that’s not even counting what inflation will do.”

Outside the kitchen window, on the other side of their redwood deck, Baxter watched a bluebird fly out of his lilac bushes. In the spring, when their flowers were most fragrant, he liked to sleep with the windows open. Winters, as harsh as they had been in recent years with the ice storms and week-long blizzards, had yet to claim a single bush. “I had no idea of the costs.”

“I figured you didn’t.” Chapelle smiled weakly. She put her hands over Baxter’s, which were still on her knees. “It’s been lots of fun having them around though, hasn’t it?”

“You need to see this,” Baxter said. He wanted to show her what he saw—two children with so much potential. The jade bangles at her wrist rattled together when he pulled her to her feet. As he followed his wife down into the basement, her heels clicking on the stairs, he heard the boys laughing.

“They’re darling,” Chapelle said, giggling. “Really.”

When he reached the landing, Baxter saw what Chapelle saw. The boys had shredded the book into confetti, which they were balling up and throwing at each other. Moulon sprang to his feet and leapt across the floor, causing Simba’s throw to miss. The confetti ball whopped into the wall, exploding into dozens of fine paper strips that lingered airborne for a moment before drifting to the carpet.

Chapelle ran her hand through Moulon’s hair. “They really are cute, aren’t they?”

Baxter drove Simba and Moulon to the overgrown fields downtown by the abandoned factories. Chapelle didn’t have the heart to come along. They had been fighting for days. She wanted to go to Europe in October and there was no way they could afford it. The $35 bill from the library to replace the shredded Cat in the Hat book was the final straw.

Sitting in the back seat, the boys were sullen. They did not point at the bulldozers and construction cranes along the way. A fire truck, lights flashing, pulled out in front of the car at an intersection. Neither boy shouted with glee. They must have known what was happening.

The sun had set by the time that Baxter found a suitable place to stop the car. He unbuckled the boys from their safety seats. Moulon would not let go of his teddy bear. Simba had been picking at his scab, causing blood to pulse from his chin. Baxter opened the glove compartment and pulled out the first aid kit.

“Come here,” he said, bending down.

He rubbed an antiseptic towelette over Simba’s chin. Touching Baxter’s hand, Simba looked at him. Baxter tore open a package of Band-Aids and pressed one over his wound.

Moulon pointed at his own chin. Even though he had no cuts, he wanted a Band-Aid too.

“Okay,” Baxter said, opening up another Band-Aid. He stuck it exactly where Moulon wanted. And he was glad, watching the boys wander into the fields, each with a fresh Band-Aid on his chin.