There were five of us, including me. My failure was a failure of nerve: I had once been in love, but I had been silent, I had suffered and enjoyed my suffering, had thought it somehow ennobling and artistic, and I had lost not only the object of my love, but the capacity for love itself, as if it were a bit of skin shed in a wound. I had wandered, I had rambled, I had learned to stop dreaming. I had stopped beneath the bridge, because I liked the shadows there, and I liked the smell of burning trash, the sharp sting in the nostrils, the grit on the tongue.

A woman with fierce red hair handed me a mask. “You lost this,” she said, and pressed it against my face. I feared for a moment that the mask would never be removed, but she pulled it away and smiled at me and I took the mask in my hand. She told me it had been mine long ago. “I’m young,” I said,

and she laughed. “You are always young,” she said, “that’s your role.” I must have looked perplexed, because she asked me if I remembered meeting the Emperor of the Moon, and I said, “No, of course not, who is he?” and she said he is the Emperor of the Moon, and she said that I visited him quite some time ago when I went out to get geese for my master and I flung a blanket over the geese and the geese flew high into the air, carrying me along with them, up through the top of the sky and to the moon, which caused me so much excitement I forgot to hold on to the blanket and the geese flew free and I fell down, down, down and landed in a lake on the moon, where three fishermen captured me in their net and declared I was the best fish they had ever caught, so they brought me to the Emperor of the Moon, who said I was a strange fish, probably some sort of pelican, and I protested that I was not a pelican, but that I was a man, and he laughed and declared that nothing so strange as I could be a man, but I said, “Of course I’m a man!” and he asked if I ever loved a woman, and I said I once loved Isabella, and he said that did not prove I was a man because after all everyone alive loved Isabella, and he stared in my eyes for a long time, seeing something no-one else could see, and then he tore off my mask and threw it toward the sky and I ran away, evading guards and jesters and courtesans, and I have been looking for my mask ever since.

and she laughed. “You are always young,” she said, “that’s your role.” I must have looked perplexed, because she asked me if I remembered meeting the Emperor of the Moon, and I said, “No, of course not, who is he?” and she said he is the Emperor of the Moon, and she said that I visited him quite some time ago when I went out to get geese for my master and I flung a blanket over the geese and the geese flew high into the air, carrying me along with them, up through the top of the sky and to the moon, which caused me so much excitement I forgot to hold on to the blanket and the geese flew free and I fell down, down, down and landed in a lake on the moon, where three fishermen captured me in their net and declared I was the best fish they had ever caught, so they brought me to the Emperor of the Moon, who said I was a strange fish, probably some sort of pelican, and I protested that I was not a pelican, but that I was a man, and he laughed and declared that nothing so strange as I could be a man, but I said, “Of course I’m a man!” and he asked if I ever loved a woman, and I said I once loved Isabella, and he said that did not prove I was a man because after all everyone alive loved Isabella, and he stared in my eyes for a long time, seeing something no-one else could see, and then he tore off my mask and threw it toward the sky and I ran away, evading guards and jesters and courtesans, and I have been looking for my mask ever since.The story of my encounter with the Emperor of the Moon became our first play. We scavenged for props and set pieces in junkyards on the outskirts of Pittsburgh, and we cobbled a wagon together from cast-off remnants of sunken boats that had washed to shore and jalopies that had jumped the bridge. The wagon was heavy even when it wasn’t laden with boards and planks and beams and tattered costumes and battered puppets. Because it was so heavy we all had to pull it along, yoked together like emaciated oxen, and by the end of a day of traveling we were always exhausted, and we collapsed to the ground with burning muscles and shredded lungs. The difficulties of travel prevented us from performing on the days when we had pulled the wagon any distance, an unfortunate situation, because once we began performing we found it painful to stop. Sometimes we stayed in a town for weeks at a time, performing continuously except for short breaks to empty our bowels or scrounge for food. By the third or fourth day, we had no audience, but we continued our performance, because to stop would have been, we all seemed to agree, to die.

It was in a small town in Ohio that exhaustion finally took its toll. We had been performing for two months at that point, making our slow way across the land, and the nights and days of endless performing interrupted only by tedious, undifferentiated hours of dragging the wagon had made us wan and hollow and listless. Sometimes ours was a play about a man who only got halfway to the moon before he fell out of the sky. Sometimes the songs we sang, which, when we had begun, had had many choruses and marvelous moments for solo kazoo, got chopped down to just a few notes, a quiet word or two, then silence. Audiences booed and hissed and spat at us and demanded their money back.

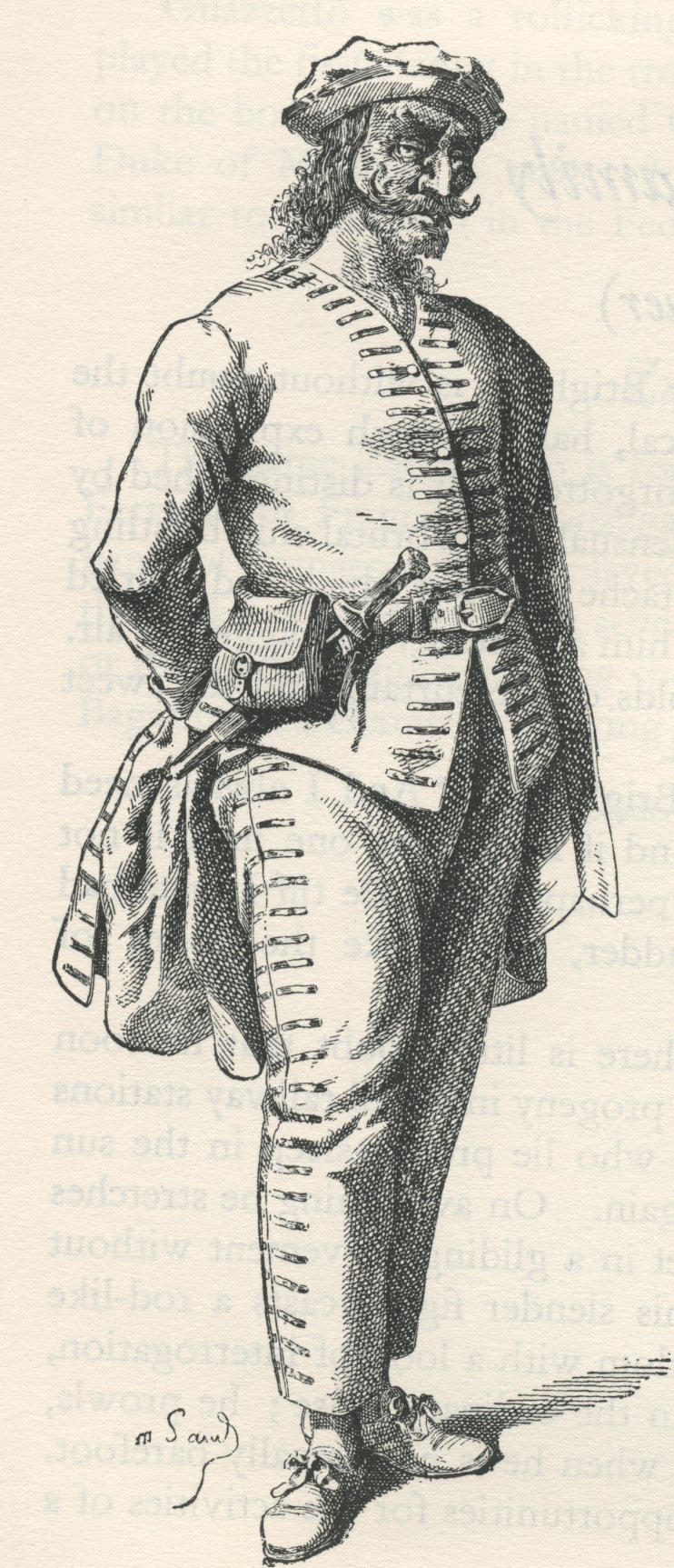

The only person who seemed to be anything other than a ghost of himself was Captain Manducus, whose real name really was Captain, because his father had been a sailor in the navy and hoped the same for his son. (“Shouldn’t he have named you Admiral?” I asked once. He said, “My father was a pragmatic man. He didn’t want to get

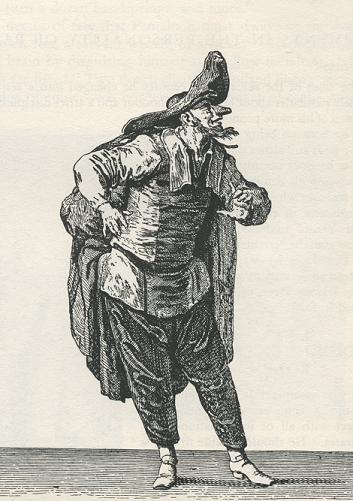

his hopes too high.”) Captain had failed to live up to his father’s most basic expectations, and had developed a severe fear of the sea. He went to business school, and, after graduating, became an expert in bankruptcy, plunging six different companies into it with great aplomb. He was born for the stage. He dressed in our most elaborate costume, one made of garbage bags elegantly rendered into a flowing cape and baggy pants, with a doublet of origamied cardboard and a hat carved from a greasy pizza box. He terrified audiences by vowing to devour their babies whole. Every time we threatened to take a day off, to wander through a town or lie out in the grass of a field, Captain told us we were becoming sorry specimens of humanity, we were letting down our audiences, we were failing once again. He climbed onto the back of the wagon and shouted at the moon: “Tonight we will come to you, tonight, tonight, tonight!”

his hopes too high.”) Captain had failed to live up to his father’s most basic expectations, and had developed a severe fear of the sea. He went to business school, and, after graduating, became an expert in bankruptcy, plunging six different companies into it with great aplomb. He was born for the stage. He dressed in our most elaborate costume, one made of garbage bags elegantly rendered into a flowing cape and baggy pants, with a doublet of origamied cardboard and a hat carved from a greasy pizza box. He terrified audiences by vowing to devour their babies whole. Every time we threatened to take a day off, to wander through a town or lie out in the grass of a field, Captain told us we were becoming sorry specimens of humanity, we were letting down our audiences, we were failing once again. He climbed onto the back of the wagon and shouted at the moon: “Tonight we will come to you, tonight, tonight, tonight!”That was the night Camerani died. We had not found food in nearly a week, and everywhere we traveled, audiences thought our show pathetic, and none of them would pay us money. A few threw rotten vegetables, and we ate them greedily. While we were performing a particularly slow version of our play, trying to conserve our energy without stepping off the stage, Camerani suddenly came to life and ran away as if struck by lightning. None of us followed him immediately, but after a few hours, I wandered in the direction he had run off, and found him lying in a pile of chicken excrement not far from where our play continued in its leisurely way. He had scared the chickens off, and in his hunger had devoured what they left behind. “I’m dying,” he said when I approached. He smiled, then issued the loudest, most horrible fart I’ve ever heard, and expired.

“We could eat him,” Captain said when I told the troupe what had happened.

“No,” said Rosalba. “Whatever killed him is still in his body. It would kill us, too.”

And so we let time and the weather wash him away, though we did not stay around to see how it did so, instead choosing to continue on, hoping we might find some place where we could eat, some audience willing to pay for what we could offer, while Camerani’s decomposition progressed in our imaginations.

“Perhaps we need a new play,” I suggested.

“We don’t know any other stories,” Captain said.

“I know many stories,” said Rosalba.

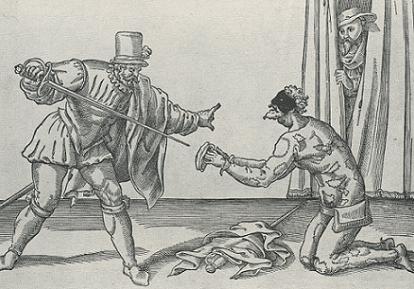

She told us the story of a man who begged for his life because he had seduced a young girl—just as the man was about to proclaim his love and devotion to the girl, the seduction was interrupted by her father, who wanted to talk to the man about a business proposal. Seeing what the young man was about to do to the girl, the father quickly tore his daughter’s clothes off and proceeded to make love to her. The young man, who was honest and honorable despite his attempt at seduction, pulled the father off of the daughter, whereupon the father gathered his clothes, dressed, pulled out his sword, and threatened to kill the young man. The young man pleaded with the father to be kind to the daughter and also to spare his life. The father enjoyed listening to the young man plead, but he was afraid of the sight of blood, and so, much to his own shame, had no intention of killing him. Instead, he handed the young man a mask that he himself had

once worn, and he insisted the young man wear it for the rest of his life. It was a dark mask with sharp eyes and it frightened the young man, but he put it on. When he felt it on his face, he knew it was a terrible mask, one that would make his every glance evil, but he did not want to die, and so he kept the mask on and fled the house. Within a few days, he was captured by police officers who had found him standing atop a pile of dead bodies, all of them men near his own age, all of them with their faces torn off. The police shot the young man, and just before he died, he removed the mask and thanked the police for their kindness. A servant of the father, a maskmaker, had watched the young man go mad, and he reported to the father and daughter what had happened, and the father celebrated while the daughter screamed and screamed and screamed until her voice disappeared and she coughed up blood.

once worn, and he insisted the young man wear it for the rest of his life. It was a dark mask with sharp eyes and it frightened the young man, but he put it on. When he felt it on his face, he knew it was a terrible mask, one that would make his every glance evil, but he did not want to die, and so he kept the mask on and fled the house. Within a few days, he was captured by police officers who had found him standing atop a pile of dead bodies, all of them men near his own age, all of them with their faces torn off. The police shot the young man, and just before he died, he removed the mask and thanked the police for their kindness. A servant of the father, a maskmaker, had watched the young man go mad, and he reported to the father and daughter what had happened, and the father celebrated while the daughter screamed and screamed and screamed until her voice disappeared and she coughed up blood.“That’s a very sad story,” I said.

“Yes,” said Rosalba, “but if Captain plays the daughter, it will be very funny.” Captain did not want to play the daughter, and so we continued to travel, continued to starve, and continued to hope another story would find us while again and again we told the tale of the man who visits the Emperor of the Moon.

Luckily, right around this time, Pulcino fell in love with me. He was the oldest of our troupe, and quite ugly, with bad posture, a big belly, pockmarked skin, and spindly chicken legs. Over the course of our starvation, though, he had become more and more beautiful. His stomach had shrunk down to a normal size, which allowed him to stand up straight, and his legs, we discovered, were muscular, though slightly feminine. His skin became smooth, its duskiness now alluring rather than seeming to be some mark of impending death. He could smile now gently and generously.

I had gone to find some water at the edge of a reservoir, and I had wanted to get away from the other members of our troupe, because Rosalba’s story still hung in my head, making me sad and wistful. The scars of my failure throbbed with each beat of my heart. Pulcino found me sitting on the grass beside the reservoir, and he sat beside me, his arm over my shoulders. He said nothing. We stayed like that for an hour or more, until finally he touched my face, turning my head toward him, and stared into my eyes. I turned away. “Why won’t you look at me?” he said. I told him I knew where this would lead. “Where?” he said. I told him it would lead to failure. “That’s what we know best, isn’t it?” he said. He held me in his arms and rested his head on the back of my neck. The sun settled behind the reservoir, tossing splinters of itself across the water. I turned back to Pulcino. He removed my mask and kissed me.

Two days later, the troupe had created a new play, a love story. We traveled to another town after our first rehearsal. The wagon felt lighter to me, and Pulcino stood beside me while we pulled it. The first audience was small, but after we had performed our love story twice, the audience grew larger, until by the second day of our continuous performances (we did not stop to eat or drink, and we were all afraid to empty our bowels after what had happened to Camerani) it seemed the entire town had come to see our play. Each person had paid five dollars for a ticket, and many people brought food and even grills so they could have a barbecue while watching us. They brought us burgers and wine and beer. They told us that they laughed and cried. Wives said they appreciated their husbands more now, husbands said they would stop hitting their wives, children promised to marry only for love, and the mayor vowed to make it illegal for anyone to kill a man who kissed a man or a woman who kissed a woman, because, he said, love is so rare in this world that we must celebrate it, whatever form it takes, and the audience stood and applauded the mayor, and all the men in the audience kissed each other, and all the women kissed each other, and all the children shouted with joy.

We were perplexed by our sudden success. The audience came back again and again. Of course, we were pleased to be able to afford hotel rooms for ourselves and to be able to replace the wagon with a pickup truck. But we all knew our story was too simple, that it hid the truth of the characters we portrayed, that it reinforced too many prejudices while seeming to be open and affirming. Rosalba played a maiden whose true love had died in a war, Captain played an evil soldier who wanted to take advantage of Rosalba’s mourning to make her marry him, I played a young artist Rosalba hired to paint a portrait of her lost love, and Pulcino played a man who bore a strange resemblance to that lost love and who served as the model for the portrait, then fell in love with my character. Captain, the evil soldier, schemed to make sure Rosalba saw Pulcino kiss me, because, being evil, he was certain it would cure her of her nostalgia and her grief, and that she would be angry with me and destroy the portrait. Instead, Rosalba was furious with Captain, because she saw through his scheming, but it was too late—Pulcino, consumed with shame, jumped off a bridge and drowned. Rosalba felt she had lost her love a second time, and she and I wandered the world together in mourning.

We played this story in town after town. With our pickup truck, we were able to travel across the country much more quickly, and soon we were in Maine, where even the hardiest fishermen broke down in tears at the end, and kissed their wives and kissed their friends. Soon enough, we replaced the pickup truck with a tractor trailer, hired a driver, and bought a bus to carry the actors and crew across the country as if we were rock stars or politicians on campaign.

It was in Boston that we first discovered other troupes trying to play our story. None of them had the success we did, the large audiences and (now) $50 tickets, but some were doing quite well, mostly by rearranging the story so that Rosalba and Pulcino fell in love. As we had become more successful and as the stages we played on had become larger, the set pieces more elaborate, we discovered that we were perfectly comfortable not performing for hours and even days at a time. We could now afford to live well, and we also had time to see some of the troupes that imitated our success.

A troupe in Texas offered something we had heard about, but never seen ourselves before. They told a similar story to all the other troupes, a variation on our story, but they did so more lewdly. Because of local strictures and statutes, none of the performers could remove all their clothes, but they found creative ways around this prohibition, and their performance was tremendously arousing. The play ended happily, with all of the lovers loving each other and the evil Captain now converted to Christianity, but the most remarkable element of the production had just begun, because the audience found the resolution so inspiring that, amidst ecstatic shouts of “Praise the Lord!” and “Hallelujah!,” nearly every member of the audience began groping the people sitting around them. They tore each other’s clothes off, they swooned, suckled, sucked

and sang; they blushed, they blew, they bleated, they blubbered all over each other until the entire theatre was a roiling mass of bliss.

and sang; they blushed, they blew, they bleated, they blubbered all over each other until the entire theatre was a roiling mass of bliss.We did not participate. It was too depressing, because we knew what it meant for us. Sitting in our hotel bar, drinking scotch and beer and vodka and wine, we reminisced about the good old days of starvation and want, the days when we feared life off of the stage, feared the death it would bring. Everything had changed, and the changes would, we knew, continue. The new sorts of plays would become vastly more popular than our play was, and though we would surely be given a theatre of our own in Las Vegas, the joy would soon be gone, and the need, as well. We had been performing once a day, and planned to reduce our performances to three per week, and we all knew we would be happiest with even fewer.

In the morning, Pulcino and I were the only members of the troupe still in the hotel. Everyone else had signed out and walked away, disappearing into the dawn. “We should go, too,” Pulcino said, “before it gets too late and people notice.”

We dressed and each packed one bag. We left the hotel through a back door and walked to a bus station, where we bought tickets to Boston. “We can head north from there,” Pulcino said. “We’ve got enough money that we can buy a house on a lake or on the ocean. It will be beautiful.” He kissed me. “Maybe we can write a book together, our memoirs. We started it all, you know.”

The closer we got to Boston, the slower the bus seemed to travel. Pulcino had gotten fat again, and he found the seats uncomfortable. His skin was thick and baggy, his face jowled, and his posture seemed to get more bent each day. I still enjoyed his jokes, but not much else, and his obsession with checking his bank accounts every few hours wore on me. By the time we got to Boston, simply sitting beside him made me grit my teeth, and the night before, as we had rested in a cheap motel room and got drunk on peach schnapps, I found myself recoiling from his touch, and he told me I didn’t love him anymore, that he was repulsive to me, and I said that was true, but not because he was fat and jowly, not because he wheezed when awake and snored when asleep, all of which I found somehow endearing, but because being loved made me sad (which was true, but just a story, and, like every story, incomplete). He held me tightly; his tears burned like acid on the skin of my back. We fell asleep together, and as I held him I knew I loved him, but only while we were in each other’s arms, and he was too much for me to hold now, and I was too little for him.

The closer we got to Boston, the slower the bus seemed to travel. Pulcino had gotten fat again, and he found the seats uncomfortable. His skin was thick and baggy, his face jowled, and his posture seemed to get more bent each day. I still enjoyed his jokes, but not much else, and his obsession with checking his bank accounts every few hours wore on me. By the time we got to Boston, simply sitting beside him made me grit my teeth, and the night before, as we had rested in a cheap motel room and got drunk on peach schnapps, I found myself recoiling from his touch, and he told me I didn’t love him anymore, that he was repulsive to me, and I said that was true, but not because he was fat and jowly, not because he wheezed when awake and snored when asleep, all of which I found somehow endearing, but because being loved made me sad (which was true, but just a story, and, like every story, incomplete). He held me tightly; his tears burned like acid on the skin of my back. We fell asleep together, and as I held him I knew I loved him, but only while we were in each other’s arms, and he was too much for me to hold now, and I was too little for him.In the bus terminal, I told Pulcino I needed to find a bathroom. I walked outside and hailed a taxi and asked the driver to take me to where I could fly away, which he interpreted as the airport, and that was good enough for me. Six hours later, having landed in Pittsburgh, I got in another taxi, and eventually, after a few wrong turns, we found the bridge I was looking for, and I paid the driver and he drove away, leaving me to stand in the twilight shadows shimmering beneath the bridge. Garbage littered the ground, and I gathered pieces of it in my hands and stuffed them into the metal basket that still stood there, apparently untouched since we had burned trash in it so long ago. I took a match from a book of matches I’d picked up at the airport bar, and I lit the trash on fire and watched it burn. I opened my suitcase, removed my mask, and placed it over my face.

Eventually, other people stood beside me at the fire. They gathered more garbage to keep the flames going, they shared cigarettes and whiskey, they muttered stories to each other, but none of them looked at me for long, and none of them wanted to remove my mask. My failure was complete.