J.E.

I knew Juan Emar intimately and yet I never knew him. He had great friends who he never met. Women who never touched more than his skin. A relative they put up with the way they put up with a long chill.

He was a quiet, cunning, singular man. He was a lazy man who worked his entire life. He went from country to country, with neither enthusiasm nor pride nor rebelliousness, exiling himself through his own decrees. Now we will try to give this exile what he never had: the nationality of love.

Our uninhabited country ignored this silent man, taking his silence as a premonition, as a mortal warning. The South American writer of his age was vociferous and solitary. Juan Emar was quiet and eccentric. Now that his contemporaries have ceased to speak and to exist, to vociferate and endure, we must decode him. He will now begin to speak to us and to receive what never mattered to him: the validation and permanence of a hero overlooked by those who were ephemeral. He hid his vanity, if he had any, in the threads of his soul. And for those who search it is a dark world: no one looks into the darkness: we all want to be part of the multitude. Juan Emar was the solitary searcher who lived amongst the multitudes without ever being seen, without ever being loved. He had no home; he was always a transient.

Now that the literary cliques are worshipping Kafka, here we have our own Kafka to take us through underground words, to lead us through labyrinths, to guide us through infinite tunnels of mystery. I was fortunate enough to have respected him in these republics of disrespect and literary treason. Here we look to writers only to give honors and awards to. It is a beehive without dignity and the best bees go elsewhere for their honey. They do good, they do bad.

My comrade Juan Emar will now get what here we are not stingy with: posthumous respect.

For in his calm delirium this man who was always ahead of his time left us as testimony a living world populated by that unreal which is always part of the permanent.

Pablo Neruda

Isla Negra, August 1970

The Green Bird (1937, from Diez)

This is what we should call this sad story. We will return to its origin, if there is anything in this life that has origin.

But this, alas, is a story that began in 1847, when a group of French scholars arrived at the mouth of the Amazon on a schooner by the name of La Gosse. They came to study the flora and fauna of this region so that on returning they could deliver a paper to the Institut des Hautes Sciences Tropicales de Montpellier.

At the end of 1847, La Gosse anchored in Manaos, and the thirty- six scholars—that was their number—in six canoes with six scholars each, went deep into the heart of the river.

Around the middle of 1848 they sailed to the village of Teffe, and by the beginning of 1849 they reached Jurua. Five months later they returned to this village hauling two more canoes filled with an assortment of peculiar zoological and botanical specimens. Immediately afterwards they sailed down the Maranon river, and by January 1st, 1850 they had set up camp in the village of Tabatinga on the shore of the aforementioned river.

Of these thirty-six scholars, I, personally, am only interested in one, which is not to say that I am ignoring the merits and wisdom of the thirty-five others. The one I am interested in is Monsieur Doctor Guy de la Crotale, fifty two years old, chubby and short, with a bushy dark beard, good-natured eyes and a rhythmic voice.

In regards to Doctor de la Crotale, I totally ignore his merits (which, to be certain, is not to deny them) and of his wisdom I don’t have the faintest idea (which is also not to deny it). As to his participation in the famous essay presented in 1857 at the Institut de Montpellier, I am not aware of any bit of it; nor do I have any idea about the work the scholars did during those long years in the jungle. All of which does not nullify the fact that Doctor Guy de la Crotale holds a great interest for me. Here are the reasons why:

Monsieur Doctor Guy de la Crotale was an extremely sentimental man and his sentiments were situated, more than anywhere else, in the birds who inhabit the skies. Of these birds, Monsieur Doctor felt a deep preference for the parrot; thus once they settled in Tabatinga, he obtained permission from his colleagues to capture one, look after it, feed it and even take it back to his country. One night, while all the parrots slept snuggled together, as is their custom, in the heights of the leafy sycamores, the doctor left his tent and walked between the trunks of birch trees, mahogany trees, and bead trees; he stepped on ferns, damiana, and peyote; entangled himself in the stems of periwinkle; smelled the foul odor of the mangachupay fruit and heard the crackling wood of the buckthorn. On a misty night, the doctor arrived at the bottom of the tallest sycamore tree; he quietly climbed it, stretched out a hand, and grabbed a parrot.

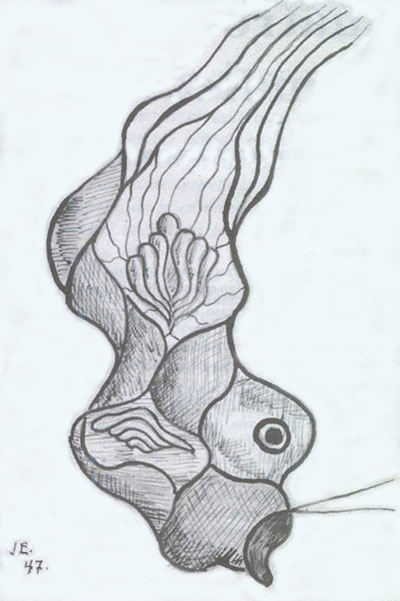

The bird was completely green except under its beak where it had two streaks of blue-black feathers. It was an average-sized parrot, about eighteen centimeters from head to the beginning of the tail, and from there about another twenty centimeters. Since this parrot is at the center of the story I am about to tell, I will give you some dates regarding his life and death.

He was born on May 5, 1821, which is to say that at the precise moment his egg broke and he entered the world, far away, very far away, on the abandoned isle of Santa Elena, the greatest of all Emperors, Napoleon I, was dying.

De la Crotale took him to France and from 1857 to 1872 he lived in Montpellier, where he was painstakingly cared for by his owner. Later in this year the doctor died. The parrot then went on to become the property of one of his nieces, Mademoiselle Marguerite de la Crotale, who two years later married Captain Henri Silure-Portune de Rascasse. This marriage was barren for four years, but on the fifth it was blessed with the birth of Henri-Guy-Hegesippe- Desire-Gaston. From his youngest age this little boy exhibited artistic inclinations, perhaps an inheritance of his grandfather’s fine tastes. This is why when he arrived in Paris at the age of seventeen—after his father was transferred to serve in the capital—Henri Guy enrolled in the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. After graduating with a degree in painting, he dedicated himself almost exclusively to portraits, and later, acutely under the influence of Chardin, he experimented with images of large still lifes with live animals. House cats appeared in his paintings amidst food and kitchen utensils; dogs appeared, chickens and canaries appeared; and on August 1, 1906, Henri-Guy sat in front of a large canvas using as a model a mahogany table atop which sat two flowerpots with mixed bouquets, a little metal box, a violin, and our parrot. But the toxins from the paint and stiffness from posing quickly began to debilitate the health of the little bird, which is why on the sixteenth of that month he cast his last breath at the same instant that the worst of the earthquakes spanked the city of Valparaiso and sternly punished the city of Santiago de Chile where today, on July 12, 1934, I write in the silence of my library.

The noble parrot of Tabatinga, who was caught by the wise professor Monsieur Doctor Guy de la Crotale and who died on the high altar of the arts in front of the painter Henri-Guy Silure-Portune de Rascasse, lived eighty-five years, three months and eleven days.

May he rest in peace.

But he didn’t rest in peace. Henri-Guy sent him to be embalmed.

The parrot stayed embalmed and mounted on a fine ebony pedestal until the end of 1915, the date the painter is thought to have died heroically in the trenches. His mother, a widow of seven years, sailed to the New World; before embarking, she auctioned off most of his furniture and possessions, including the parrot of Tabatinga.

He was acquired by old father Serpentaire who owned a shop at 3 rue Chaptal that sold trinkets, antiques of little value, and embalmed animals. The parrot stayed there until 1924. But that year things changed, and here are the reasons and circumstances:

In April I arrived in Paris and, with various compatriots, we dedicated ourselves, night after night, to the most extraordinary and joyful revelry. Our preferred neighborhood was lower Montmartre. We were the most faithful clientele of every cabaret on the rue Fontaine, the rue Pigalle, the boulevard Clichy or the place Blanche; and our preferred spot was, without a doubt, el Palermo, where, in between the performance of two jazz bands, an Argentinean orchestra played tangos as sticky as caramel.

At the sound of their bandoneones we lost our heads; the champagne flowed into our mouths and when the first voice—a heartbreaking baritone—broke into song, we were on the verge of insanity.

Of all the tangos, one was my absolute favorite. It struck me the first time I heard it—it’s better to say “I noted it,” and yet, I think, I isolated it—a new emotional state passed through me, some new psychic element was born inside me, breaking and dwelling within me—like the parrot breaking out of its egg and dwelling amongst the gigantic sycamores—submerging itself, fortifying itself, and enduring the long notes of this tango. A coincidence, a simultaneity without any doubt. And although this new psychic element never shed light on my consciousness, it so happened that as soon as those chords broke I knew with all my being, from my hairs to my feet, that those chords were filled with deep meaning for me. So I danced, clutching my partner close to me, whomever she happened to be, with longing and tenderness and feeling a vague compassion for all that I myself was not, entangled with her and my tango.

And that baritone from el Palermo sang:

I have seen a green bird

Bathe itself in roses

And in a crystal vase

A carnation’s leafless poses …

“I have seen a green bird …” This was the phrase—in the beginning it was hummed, but later only spoken—which expressed all my emotions. I used it for everything, and for everything it was perfect. Later my friends started using it to describe anything blurry or ambiguous. For it encapsulated a whole range of secret codes and was flexible enough to fulfill an infinite amount of possibilities.

In this way, if any of them had big news to tell, a success, a conquest, a triumph, he would clasp his hands together and say joyfully:

—I have seen a green bird!

And if he were concerned or annoyed, in a low voice, with panicked eyes, pouting lips, he would say:

—I have seen a green bird!

It was used for everything. In reality there was no need to be understood, to express how much you wanted to entrench yourself in the subtlest creases of your soul, it wasn’t necessary, I say, to use any other phrase. And life, expressed with this succinctness, took on a certain peculiar shape; it formed a parallel life which sometimes explained this life, sometimes complicated it, often filled it with an urgency whose depths we could not penetrate.

Later, after we got home from our parties, we would suddenly fall into uncontrollable fits of laughter at the mere thought of the words:

—I have seen a green bird. And if, for example, I looked at my bed, my hat or out the window at the roofs of Paris, that laughter, its tickle, poured a new drop of compassion over humanity, while scorning the unhappiness of those who have not been able, not even once, to reduce their existence to one single phrase which compresses, condenses, and even fructifies every single thing.

In truth, he has seen a green bird.

And in truth, it could be that right now he is laughing at and understanding the desolation of humanity.

One October afternoon he went out to other neighborhoods. Visiting different bars in the afternoon and different boites in the evening, after a succulent meal he went home with a dizzy head, his liver and kidneys pumping energetically.

The next day, when at seven in the evening his friends phoned to meet for their nightly adventure, his nurse said that it would be impossible for him to accompany them.

They went around to their favorite places, and between champagne, dancing, and dinner, the sun rose and the magnificent autumn morning caught them by surprise.

With their arms around each other, singing the songs they had just heard, hats tucked over their eyes or ears, they walked down the rue Blanche and winded their way onto the rue Chaptal in search of the rue Notre Dame de Lorette, where two of them lived. And as they passed number three of the second street cited, pere Serpentaire was opening his little shop and appeared in the window confronted by the astonished looks on the faces of my friends, who saw before them, on its ebony pedestal, the bird of Tabatinga.

One cried:

—The green bird!

And the rest of them, more than amazed, fearing that they were in the throes of an alcoholic vision or a hallucination, repeated in a hypnotic voice:

—The green bird ….

A moment later, after they recovered their senses, they rushed into the store and immediately asked for the little bird. Pere Serpentaire wanted eleven francs for the bird and my good friends, thrilled to tears with their discovery, doubled the price and deposited into the hands of the stunned old man twenty-two francs.

They remembered their sick friend and went straight to his house. They ran up the stairs, much to the disturbance of the concierge, knocked on the door, and gave him the bird. And in one voice they sang:

I have seen a green bird

Bathe itself in roses

And in a crystal vase

A carnation’s leafless poses. …

The parrot of Tabatinga was placed on the work table, where he gazed out the window onto a portrait of Baudelaire on a mural outside, and there he accompanied me the remaining four years I stayed in Paris.

At the end of 1928 I returned to Chile. Safely packed in my suitcase, the green bird once again sailed across the Atlantic; he passed through Buenos Aires and the pampas, trekked through the mountains, arrived at Mapocho station; and on January 7, 1929, his glass eyes, accustomed to the image of the poet, curiously contemplated the dusty porch of my house and, later, in my study, a bust of our national hero Arturo Prat.

The next year was spent in peace. The next in the same manner, bringing us to 1931, which entered with a terrifying bang.

And here begins a new story.

January 1st of this same year—which is to say (perhaps this date is superfluous, but as I write it comes to my pen) eighty-one years after the arrival of Doctor Guy de la Crotale in Tabatinga—my uncle Jose Pedro arrived in Santiago from the saltpeter mines of Antafogasta, and when he saw that there was an empty room in my house he asked if he could stay in it.

My uncle Jose Pedro was a scholarly man, who believed that his most sacred duty in life was to give long didactic speeches to the youth, and he was especially fond of preaching to one youth in particular. His stay in my house provided precious opportunities. Every day during lunch, each evening after dinner, my uncle spoke in a soft voice about how horrible it was that I preferred the Parisian nightlife to the more dignified Paris of La Sorbonne.

On the night of February 9th, sipping coffee in my study, my uncle suddenly pointed his finger and asked about the green bird:

—And that parrot?

In simple terms I told him how it made its way into my hands after my best friends spent a night drinking and how I was not able to join them because the night before I drank and ate too much. My uncle Jose Pedro flashed me a stern look and then, perched over the bird, he exlaimed:

—Damned beast!

That was it.

This was the unraveling, the cataclysm, the catastrophe. This was the end of his destiny and the beginning of a total change in my life. This—I happened to notice the exact time on my wall clock—took place at two minutes and forty-eight seconds after ten on the fatal night of February 9, 1931.

—Damned beast!

As the last echo of the “t” reverberated, the parrot spread its wings, fluttered them with a dizzying quickness, and took flight with the ebony pedestal still stuck to his feet, he crossed the room and, like a missile, landed on the skull of poor uncle Jose Pedro.

I remember perfectly how the pedestal, on landing, spun like a pendulum and struck with its base—it must have been pretty dirty—as it left a great stain on my uncle’s elegant white tie. The parrot attacked his bald head. His forehead cracked, and out poured something like a stream of volcanic lava. It flowed out, bubbled, and a lumpy gray mass spilled out of his brain as trickles of blood ran down his face and left temple. Thus the silence that erupted when the bird took flight was interrupted by the most horrible scream. I was paralyzed, frozen, petrified. I did not know any man could scream in this way, let alone my kind uncle who always spoke so softly.

Intent on destroying the evil bird with one blow, I picked up the brass pestle from an old mortar and lunged towards the two of them.

Three lunges and I raised my weapon right as the bird was about to launch a second attack. But the beast restrained itself, turned its eyes towards me and with a swift jolt of his head, promptly asked:

—Senor Juan Emar, would you be so kind as to do me a favor?

Naturally, I responded:

—At your service.

During my sudden paralysis, he launched his second attack. A new gash, new gray matter, new trickles of blood, and a new scream, but this time more stifled, more debilitated.

Once more my senses returned and with that came a clearer notion of my duty. I raised my weapon. But the parrot fixed his eyes on me again and again he began to speak.

—Senor Juan Em ….

Praying this would end quickly, I said:

—At your serv …

Third attack. My uncle lost an eye. The way one uses a spoon, the parrot used his beak to scoop out his eyeball, which he spat at my feet.

My uncle’s eye was a perfect sphere except at the point opposite the pupil, where a little tail stuck out, immediately reminding me of the agile tadpoles that live in swamps. From this tail grew a thin scarlet thread connecting up to the cavity formerly occupied by my uncle’s eye; and this thread, with each desperate movement my uncle made, extended, shortened, quivered, but never ripped, and the actual eye stayed motionless as if stuck to the floor. The eye was, I repeat—with the exception of the deviations I have already mentioned—perfectly spherical. It was white, like a little ball of ivory. I always imagined that the back of the eye ball—and especially in the elderly—would be lightly toasted. But no: white, white like a little ball of ivory.

Over this whiteness, with grace and subtlety, ran a streak of thin pink veins which, when mixed with other cobalt colored veins, formed a beautiful filigree, so beautiful that when it seemed to move it slipped over the white moistness, propelling itself into the air like a flying illuminated spider web.

But no. Nothing moved. It was an illusion born out of the desire—a fairly legitimate one, to be sure—that so much beauty and grace could exist, could come to life, levitate, and captivate the viewer with its multiple forms.

A third scream sent me back to my duty. A scream? Not exactly. A weak moan; that is, a weak moan but sufficient enough, like I’ve said, to send me back to my duty.

A lunge, a whistle, and in my hand appeared the brass pestle. The parrot turned to look at me.

—El senor Ju …?

And I quickly:

—At your serv …

A moment. Frozen. Fourth attack.

This one came down at the top of my uncle’s nose and ended by its base. That is to say, the bird ripped the nose from his face.

My uncle was an extraordinary spectacle. Bubbling at the top of his skull, in two craters, was the lava of his mind; the scarlet thread quivered from the hollow of his eye; and in the triangle left by the absence of his nose, from the pulsation of his heavy breathing, a dense clot of blood appeared and disappeared, swelled and sucked.

Now there were neither screams nor moans. Somehow his other eye, from between its fallen eyelids, managed to shoot me an anguished glance. I felt it stab into my heart, filling it with all of the tenderness and all of the memories which I attached to my uncle. I turned frantic and blind. As my arms fell, my ears heard the sound of a whisper:

—El sen …?

And I heard my lips respond:

—At your ….

Fifth attack. He wrenched off his chin. It rolled down my uncle’s chest and, as it rubbed against his elegant white tie, it cleaned off some of the dust left by the pedestal and in its place left a detached yellow tooth which shined like topaz. Up above the bubbling stopped, the dense gushing no longer appeared and disappeared around the nasal triangle, the thread from the eye ripped, and the chin, on falling to the floor, sounded like the beat of a drum. Then his two shriveled hands fell together and from his sharp finger nails, pointing inertly towards the ground, dripped ten tears of perspiration.

A soft whisper sounded. A death rattle. Silence.

My uncle Jose Pedro died.

The clock on the wall read three minutes and fifty-six seconds after ten. The whole scene lasted one minute and eight seconds.

Afterwards, the green bird froze for a moment, then extended his wings, fluttered them violently, and took flight. Like a hawk above its prey, it stayed suspended in the middle of the room, its trembling wings like raindrops on ice. And with all of this the pedestal balanced itself to the rhythm of the clock on the wall.

Soon the beast circled the room and finally settled, or, better said, settled its ebony foot on the table and fixed his glass eyes on the bust of Arturo Prat.

It was four minutes and nineteen seconds after ten.

My uncle’s funeral took place on the morning of February 11th.

As we carried the coffin to the carriage, we passed the window of my study. My family did not notice when I looked inside. There my parrot sat motionless with its back turned to me.

The enormous amount of hatred emitted from my eyes should have weighed heavily on his feathers, even more so if we add to its weight the weight of the words whispered by my lips.

—I’ll get you back, you filthy bird.

At that moment his head quickly spun around and he winked an eye and opened up his beak to speak. And since I knew perfectly well what question he was going to ask me, I winked back and, with a slight gesture, I gave him an affirmation which, if translated into words, would sound something like:

—At your service.

I returned to my house at lunch time. Sitting alone at the table, I missed my dear uncle’s lectures on morality; I think of them every day and send loving thoughts to his grave.

Today, July 12, 1934, it has been three years, four months and three days since my kind uncle passed away. For those who know me my life during this time has been the same as always, but in truth there has been a radical change.

Around my companions I have fallen into a complacency; whenever they want something from me, I bow and say:

—At your service.

And I myself have become so much more affable; before doing any kind of task, I imagine that task as a giant woman standing in front of me, to whom I bow and say:

—At your service.

And I see that this smiling woman slowly turns from me and walks away. There is nothing I am able to do.

But most everything else, as I have said, has stayed the same: I sleep well, I have a strong appetite, I walk happily through the streets, I talk enthusiastically to my friends, I go out drinking some nights, and I have, or so I am told, a woman who loves me dearly.

As far as the green bird goes, he is here, frozen in silence. Every now and then, I offer him a token of friendship and in a soft voice I sing:

I have seen a green bird

Bathe itself in roses

And in a crystal vase

A carnation’s leafless poses …

He never moves and he never says a word.

“The Green Bird” is from Diez by Juan Emar, copyright 1972 (originally published in 1937), Editorial Universitaria, Santiago, Chile. Published here with the permission of Editorial Universitaria.