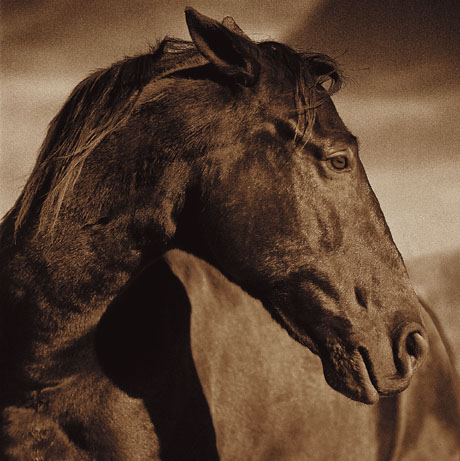

Everything swims up into its eyes. Its agility, its strength, its swiftness: These qualities soften though they do not lessen as they rise. The horse is the most important animal in history, longest and most faithful in its service to man. To be a tamer of horses was once one of the noblest of callings. Time and time again, the horse has faced extinction, but as man’s companion it has survived. It has ploughed our fields and carried us to war; it has furnished us our sport or been a cheaper, more reliable, much safer, less invasive motorcar. It has never been a pet. Though sometimes mistreated, it has never been a slave.

Curious, intense, warm, wary, sad, their eyes seem to see simultaneously straight ahead and to the side, past us, through us, right to our weaknesses, which they forgive. These photographs do not deny the horse’s history or our gratitude, and they certainly display the inherent grace that has been so long admired. But they bring out the sculptural character of the head; they liquidize the eyes; they celebrate the horse’s mottled, subtle hide. Whatever its position, the horse is looking at us. They know how to draw a line. Or turn their mane into a shower of light. And the ears, like a bat or a bird that has just lit on a little hill, stand, swivel, listen. The nostrils are the most mysterious, the way entrances to caves are, where the horses, in quiet, examine our odor as if it were a resume, and we, not they, were for hire.

We shall never see them this way while we ride, or while they graze, or merely exercise. Only this lens lets us see them in terms of their colors, their sinews, their veins, their strength, their poise: lets us look into the other meadow of their lives.

—William H. Gass

No. 1

No. 3

No. 7

No. 9

No. 12

No. 13

No. 14

No. 16

No. 17

No. 18

No. 19

No. 22

No. 22

No. 22