If you stand too close you only see disconnected lines, the splatters, the idiosyncratic blots, Rorschachs of indeterminate personality.

If you stand too far you just see a mass of paint squared on the wall among other masses of paint from the other paintings in the gallery.

But if you stand just far enough away the lines move, the painting engulfs and absorbs you in its patterns, in its rhythms, so that there isn’t anything else but the paint, the lines, the motion. One moment it flies apart, you are scattered in an exploding universe; the next it contracts, falling back into itself, you shrink, back into yourself, nowhere, into nothing, you are lost. When you close your eyes, an afterimage of chaos.

Madness.

Yet the large painting has presence and looks to point to something still larger, as if it stands at the threshold of some kind of meaning within us, without, within and without and beyond.

Assumed is that art has anything to do with life.

And it’s the painting that most engages my brother among the other abstract paintings, after all the other galleries, after all the centuries when painters painted pictures that looked like something, that represented whatever they thought worth representing—fruit, flowers, and skulls; landscapes and cities and interiors, and battlefields and ruins; peasants and rural folk set in genres and allegories; royalty, nobles, statesmen, and generals, their outer lives, epic scenes of their triumphs and defeats; the inner strain, the quiet joys, the vague room of unknown people; soft, fleshy nudes and hard-edged gilded saints; gods and demons and monsters and heroes of varying alignments, from around the world, from above and beyond and beneath it; and Christ and his followers, their trials and blood, and his unscathed mother, sitting; and Socrates, also sitting, taking the drink, pointing the finger up; and Buddha, not pointing, squatting, taking the break: the faces, the places, the objects of longing and despair; people, nature, the culture contained in perspective boxes or turned loose in flights into infinity or flattened on the picture plane, space disrupted, perspective collapsed—it’s the Pollock that makes him stop and look.

With the image of his standing there, a possible connection, an identification of my brother with the painter: my brother looking, motionless and absorbed; Pollock moving when he paints, absorbed—I have seen the Namuth footage and photographs—Pollock stepping over and around and in and on the canvas he spreads on the floor before he nails it on a stretcher, dancing with a halting yet certain grace.

—Hey Vito.

Seven years later I am looking at my brother propped up in a hospital bed in the oncology ward at Duke, his voice weak and hoarse.

—Sheesh, all this stuff they do to youse here, he says. It makes you sound like a gangstah.

Forty pounds gone, his hair thinned to baldness, his cheeks limp, their flesh yellow and blotched, his hollowed face nearly a skull.

—Hey Vito. Come and kiss my hand.

A sense of humor, my brother.

A few months later he was dead.

That was thirty-five years ago. I have never been closer to anyone else since or yet closed the breach.

I think I might yet discover a way to join the moments and trace a plot, gain a perspective that aligns and explains, that I might reach some understanding, might yet discover my place in the world, make a connection of life past with life present and whatever lies ahead—

Or at least, at last, find a way to put the last memory behind me.

But fear I will fall into another descent from which there may be no escape.

Every glance, every essay, risks a small death that flits above the greater.

In the thirty-five years since I only know I do not know how I fit in a world I do not understand or where I belong in a country I no longer recognize, a country that eternally renews itself in unrecognizable ways.

But my brother, before the Pollock, looks composed and engaged, all there.

Maybe from the depths, de profundis, release, a revelation—

Of what?

What is needed is a chart, a plan, a set of rules. Or at least a dance chart to tell us where to put one foot after the other …

Plot:

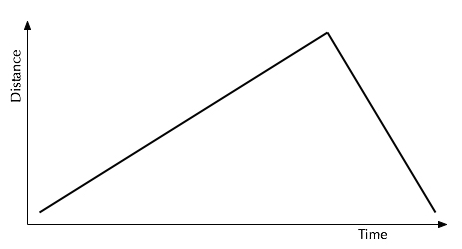

We all want to believe that a light shines on us individually and makes us each protagonists in life’s contests. Plot restores our faith in action and makes our lives seem real. It is a way to order events and give them direction in the stories we tell about ourselves, to take us from beginnings to endings, to chart our paths in the world. A mistake, a flaw, a motive separates us from the baseline of the world, causing tension that rises over time and propels the plot and increases our distance from the world until a point is reached beyond which the strain can go no further, the climax, which is followed by an unwinding that returns us to the world, a falling into one kind of resolution or another.

Plot depends not just on our understanding of who we are and what makes us tick, but also on the way the world works, or the way we think it works, and what moves it. But more than that. Plot can also be built on an idea, an understanding, a projection of who we can be, should be, what matters, how our lives should begin and end, what is beyond us. Plot implies perspective.

Perspective:

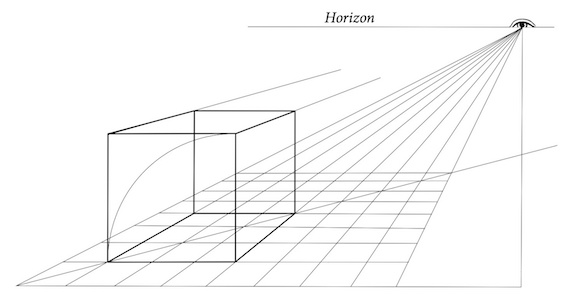

A horizon is set towards which lines that define space converge, theoretically at infinity. A central point on the horizon, the eye point, marks the spot and determines the overall cast. It’s a device for creating the appearance of depth in two-dimensional pictures that look like something, a way of establishing relationships, consistent and proportional, between up and down, here and there, anywhere in the frame.

But more than an appearance, a metaphor. There’s a figure in the figure. Not just a way of relating parts, of ordering space consistently and proportionally, but also a vehicle for notions of consistency and proportion. Not just an orderly picture, but a picture of order. Not just deep space, but a schema for the concept of depth. Since the eye point lies at an infinite distance, we are given a container for all the world. And since we can see that point and all it determines, we have the means to comprehend it. Perspective implies perspective, a framework that holds the world we see, a world where we see each other and are seen, where we have a place, where everything fits, a world governed by whatever it is that exists between and beyond us and holds all things together.

In his fresco The School of Athens, Raphael set the Greek philosophers in a volume of Renaissance architecture. At the center stand Plato and Aristotle, representatives of ideal forms beyond and their particular manifestations here on earth, these two surrounded by the others in animated talk and gestures, their disputation contained by and aligned within the receding vaults determined by lines of perspective, those lines leading in the distance to soft clouds and open blue sky, their focal point placed behind the two commanding figures. In Leonardo’s The Last Supper, the vanishing point, God’s eye, is directly behind Christ’s head, which sets the perspective that frames the chamber and aligns what he lays before his agitated disciples. In the distance, mysterious blue hills and the fading light. In both a box is constructed that proposes, contains, and opens up, each holding and balancing turmoil and reason, spirit and the body, each setting a trajectory that tells a story about disorder and resolution, fall and redemption, each plotting a course for our life on earth and a life everlasting.

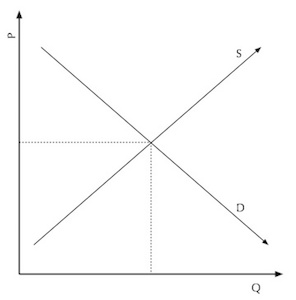

Supply and demand:

A graph that tells a story and paints a picture, where desire and assertion find happy intersection in the world.

On the face of things, they could not have been more different. Pollock came out black, strangled by the cord, and grew up in a poor family, out West. His father split. His education was spotty, and he only had brief, fragmented training in his field. Rough in manner and reticent to the point of pain, he was given to periods of total withdrawal and sporadic bursts of violence, usually harmless but senseless, or could break into tears over nothing. Professionals and amateurs alike diagnosed him with a bouquet of psychological disorders. We never would have heard of him had he not become an artist. Friends and family, however, remained closely attached. And he did become an artist, the leading figure of the Abstract Expressionist movement. Left behind all those paintings.

A poster baby, my brother grew up in a stable middle-class family down South, and his life was a straight line to success. Valedictorian in high school, he received a full scholarship through college, Chapel Hill, and went to Harvard for his MBA. After graduating he worked in investment banking, first with a small outfit in New York, followed by a few years with American General in Houston—his exile, he called it—then back in New York with First Boston, in its day the firm where Ivy Leaguers would have sold their soul to land a job, if souls are what we have. Articulate and charming, even courtly, he had a strong, flexible mind and a quick wit. He could put on the mask of sobriety and order one moment, then, with a quick grin, a sudden wide-eyed glance, and an open-handed gesture, throw everything up for grabs. Perhaps that is not a difference, but he stayed in control and by all current standards was considered sane. Didn’t leave anything behind.

He did write reports for First Boston, though the exec above him put his name on top, a sore point. I still have them, but, as they are impenetrable in dense, arcane financial language, I don’t know what to make of them or how they might relate to anything outside the world of finance. Also the Wall Street Journal called for his opinion. He analyzed banks, his angle on the economy, and created a computer model for doing so that the firm praised.

Reputation cannot be the point, however, as it doesn’t matter, or doesn’t matter to me now. What matters is who they were, how they lived, a way of being, a way to keep oneself whole—

Or keep oneself from going under—

What matters most is finding out what matters.

Surface differences, however, can cover essential similarities. Both were ambitious and driven, both made their splash in New York, and both hit their stride in the postwar boom, Pollock in the lead. Both drank a lot. Both had a way of holding a cigarette as if defining a point around which the world might gather. Neither was political or believed in anything specific, though both had a sense of something Out There towards which they directed their gaze. Both acted in such a way that their own lives didn’t matter. I don’t know if that is faith or self-destruction. And both went out early, Pollock at forty-four, a car crash while drunk with two others on board; my brother, thirty-four, from an illness for which his doctors could not pin down a cause. But both showed signs of strain well before, prematurely receding hairlines and loss of definition in their faces. Pollock’s death was preceded by years of inactivity and depression, while my brother was starting to lose control. A year before he died I got an urgent phone call, incoherent and desperate. I flew over to try to help and saw he had smashed every mirror in his apartment.

What is essential here, what is noise?

But a plot is suggested, a familiar story with a point. Insecurity can propel leaps as much as certainty and drive ambition. Pollock broke the rules of convention and flung paint, projecting himself as the artist in the act of painting, leaving the traces on huge canvases to distinguish himself from the crowd and become the great painter. My brother, ever sure of himself, took the route of money, endless in how much it can inflate. Pollock increased his output for the annual shows, fifty paintings one year, making paintings that didn’t look like anything, that didn’t look like anything in different ways, ever pushing the ceiling of what we thought we were supposed to see. My brother put in eighty-hour weeks, looking to extend his grip on the upward flow of cash. Either way, both followed a course that returned nothing but the demand to keep pushing and provided no image of themselves other than the face of what they sought, the demand feeding the image in endless reflection.

We have often been told such stories before, though do not hear them much now. Their purpose, I suppose, is to restore balance in the world, though it is not always clear what is being weighed or what value there is in balance. Not considered in those stories, however, is the world in which they tried to find a place, above which they tried to soar.

Pollock came of age between the wars that leveled assumptions western civilization rested on, during the Depression, which leveled still more. He lived off scant WPA checks for artists at a time when there was not much support or interest in the visual arts other than the regional mannerisms of Thomas Hart Benton, under whom he briefly studied, Grant Wood, John Steuart Curry, and others, who painted pictures of basic folk in fabled rural settings at a time when the Dust Bowl and farm foreclosures forced mass migrations, when Hoovervilles spread in urban fields and bread lines stretched for blocks and factories lay empty, even though Americans had the desire and ability to make and buy and plow and reap. As Pollock’s work developed there still was little recognition outside Manhattan of much art that strayed from the familiar. When his reputation took hold, the early 1950s, he was a few years from his death, my brother grew up, and I was born, a time of fabled materialism, conformity, and suspicion, when faith in the invisible hand was ascendent. Really, though, it was a era of its own wildness and excess. Joe McCarthy after all, a hard drinking and freewheeling player, was a beat in his own way, who cut loose in the hearings, staging happenings that gave us a spectacle we could not find elsewhere.

In my brother’s time, when I was growing up, before the lights went back up in Times Square, New York’s extravagant palaces of spectacle had been sectioned off into small screening rooms and portaled cubicles that smelled of Lysol, Times Square now both the locus and symbol of urban pathology, represented in many films. The city was in debt and talked of default, its infrastructure was in disrepair, and the murder rate soared, over fifty one week. Off the streets, dark recesses not entered; on them, the habit of keeping to oneself and avoiding glances. As for the nation, riots and assassinations and another war that divided us down the middle, while on the horizon, beyond and above us, the vanishing point of nuclear annihilation. Then, as I went out into the world, a period of economic stagnation and decades without focus that I have trouble accounting for. Yet still we we kept our faith in the market and our native ways.

How can our course be plotted when the ground beneath is slipping? Or pathologies of the self be separated from those in the world? Or a complete picture made when our ways of looking are narrow and insubstantial?

Perspective, concerns:

The place we have in the order of things may not be the place we want. Perspective space was also used to sound the depths of hell or, in the works of Piranesi, set ruins of antiquity in deserted landscapes or create vast, dark prisons, intricate and seemingly endless.

It is hard to stare down the throat of infinity very long.

There are no absolutes.

Corot, Cézanne, cubism, etc.

Dizziness …

I suppose there is indulgence in analyzing bank stocks and making paintings that don’t look like anything. Then again we have to do something with ourselves and express it and give it some kind of value. But Pollock’s sales and recognition came late, not long before his death, and his larger exposure in the country stirred only curiosity and derision. My brother invested little and didn’t do much with what he had. Neither had much of a life outside their work. Both, however, were once engaged by much that lay beyond.

Banks represent the agency that manages value and negotiates the possibilities that underwrite the world, which must have been the attraction. Lately I have gone through my files of the papers he left to see what I can glean. His model to assess banks, adopted by the firm and passed on to the industry, looks, as he states, beyond the volatility of surface transactions to an understanding of how bank management and bank functions work together and translate into performance, using levels of assumptions built in to assess the data, assumptions that could be adjusted to meet changes in the financial world, at the time uncertain. I have also given his First Boston reports another shot, one on refinancing New York’s debt with some hope for the short term but doubts about long-term financing, others on Morgan Stanley, J. P. Morgan, Chase, and Citicorp, where he looks ahead critically and cautiously. Between the lines the light of hope—or is the glare of recognition?

Pollock was a serious artist, for which he was later mocked. Formal and expressive demands mattered to him, and he insisted he always had an image in mind, but that he veiled it. He was sensitive to the motions of nature, within, without. The vast, open spaces of the West and its subdued colors left an impression. While his exposure to art was not extensive, he held close the artists who moved him, past and present, touching in them the essential. As a boy he was taken by Orozco’s Prometheus, Prometheus the Titan who gave us fire and inspiration, whose muscular figure pushes up and strains against the gothic arch that frames the mural while surrounded by bowed or lifted heads of us around him, troubled and diminished. Under Benton, at the Art Students League, he copied Rubens, Michelangelo, Rembrandt, and El Greco, from whom he learned the possibilities of size and the energy of rhythms and the subtleties of tonal contrasts. Along with Orozco, the other Mexican muralists Siqueiros and Rivera, who projected size and message into the world. From Europe, the surrealists Miró and Masson, what they turned loose from from what they thought lay within, the cryptic messages of desire, but also Mondrian, his strict forms of geometry, his precise compositions. At home he was moved by the dark, brooding landscapes of Ryder as well as Native American masks and totems, faces of tribal identity, emblems of collective restraint, that externalized common fears and contained communal desires and displaced the desire for violence. And, like the other artists of his time, by Picasso, who changed the landscape.

Everything my brother touched came to life, and looking at what he discovered as I grew up opened up the world. It wasn’t so much the things themselves but what he invested in them and what they returned, a quickness of the spirit, a fullness of understanding, precise and robust, those and still something else. First it was science and science fiction, their possibilities. He read Asimov and Scientific American, experimented and made things—a simple computer, a model of the moon circling the earth—and excelled in math, broaching its more abstruse operations. He was also accepted at MIT undergrad, though I don’t know what his plan was. Then he branched out into the stuff of life and its contradictions, reaching for other insights and the larger view. At UNC he double-majored in English and economics, complements perhaps in his thinking or a division to maintain a complex self in a complex world. He also took courses in political science and psychology, while extramurally his study was sex. And he kept reading by himself, for himself, outside the classroom and after he left school. The standard works from the past, and Hemingway and Roth, models of the male stance and of edge and detachment, but also Joyce, Beckett, Barth, and Pynchon, their long, difficult novels of systems and meanings, or nonmeanings, of large schemes and larger doubts, of assertion and comic undercutting. There wasn’t anything he closed out or would not entertain.

Reading means nothing unless you become absorbed in the details, unless it charges the blood, breaks thought, expands it, and takes you someplace else. It was seeing that in my brother that got me started reading myself, and he encouraged me and passed on recommendations. I still have his copies of Moby-Dick, books by and on Marx and Freud, and Norman O. Brown’s Life against Death, extensively underlined. These became part of a growing conversation between us that went on for years. While in college I studied art, literature, and philosophy, moving further out on my own and adding to our exploration. When I visited him in New York I found the museums and galleries and theaters off and off-off-Broadway—Long Day’s Journey into Night, Buried Child, American Buffalo—those visits followed by more talk in bars or back at his apartment or months later over the phone, where we spent hours deep into the night, finding threads or cutting them, extending the conversation, further out, further in, getting lost yet still returning.

To be engaged, however, is not the same as being located or whole. Guernica was the Picasso that most struck Pollock, the monumental tableau of twentieth-century slaughter and mutilation under the light of a single, naked bulb, painted at a time when tribal violence had been unleashed throughout the world. My brother also read closely Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead and Heller’s Catch-22, novels looking at that war to view present corruption, and Gaddis’s JR, his dissection of capitalism and the American dream.

Pollock went to a Jungian therapist to treat his mental disorder and was asked to bring sketches to the sessions, the therapist’s idea being that by tapping universal images of the cycles of life and death he could find balance and restoration within. Really he was working out images he took from Picasso—a wounded horse, painfully involuted, a mesmeric bull in heavy outline—and other figures that found their way into his work—monsters impacted and convoluted, impossible to identify, groups of them compressed into inseparable mass—and frenetic linear drawings without clear suggested image—angular or sinuous, dense and taut or openly released across the paper—that anticipated the allover paintings. What part of Picasso’s world, still his, did Pollock try to tap, what did he internalize to express what was going on inside his head? How can it be decided if the images moved towards resolution or away from it, exacerbating his conflicts? Or that he didn’t find balance in compromises with what could not be taken head on or resolved?

What is flight, what is garbling, what is obsession, what is vision, what is seeing closely what most of us manage to avoid? The critical interpretations are no help. His work invites as much as it deflects.

The time of our talk also marked the beginning of a period of deepening stress and isolation for us both. I got an ulcer at twenty-five; my brother could not sleep. Still we talked, but found no causes or solutions, or too many, and our conversations often collapsed into silence.

I have another file of notes on legal pads my brother made in his last years, where in lists and charts he reviews his performance, his place, his role in the firm, and First Boston’s performance, its position in the financial world, his objective being to set for himself one-, five-, and ten-to-fifteen-year plans—not completed. On other pages he reviews himself as a person in more lists, critical, introspective, and comprehensive, with bullet points of his strengths and doubts and fears and uncertainties—inconclusive.

Many saw the Pollock drip paintings as the high point of his work, a culmination, as progress and an influence on later artists. Progress towards what, with what influence? Missed is the variety and formal invention and expressive power and originality in all his work, start to end, how much he looked back at what he had done before, how much he did not follow trends or match expectations, how much he left unresolved. Direct figuration reappeared in his late work, which caused a stir. In one of his last paintings, Portrait and a Dream, another large, wide canvas, he painted on the right a face—self-portrait, he tells us—drawn in heavy outline and partly filled in with black forms and colored shadings. On the right side of the face there is a large bulge that covers the eye and cheek, that swells towards and looks at the other side of the canvas, at a large, black linear mass of disturbingly suggestive but unidentifiable shapes—the dream. Between the portrait and the dream and surrounding them, a field of blank space.

Perspective, concerns:

Modern artists rejected perspective space as a trick, an illusion, that could not capture fleeting light, the transience of surfaces. Or its balance and hierarchy of scale could not express the disproportions artists felt within and saw without. Or it forced design and constrained the possibilities of composition. Or it violated the integrity of the picture plane, of the materiality of paint, of the point of art itself.

Our spiritual aspirations, we have realized, can oppress, and our orderly schemes can mask cultural imposition or project inverted desires and disorders into the appearance of depth and resolution. Those discoveries were a source of marvel for a while, though they fizzle now.

Nor have we found a way to connect a subject with an object or even make sense of those terms. Our logical propositions we now concede cannot see outside themselves.

We flounder with ethics because we cannot anchor such thought. We don’t tell stories with a moral because we have suspicions about that term as well, or do not understand it, or have replaced it with others.

We have information that we accumulate in prodigious amounts, ever increasing prodigiously, its size and the process of accumulation themselves sources of wonder, yet we have nothing to bring facts together other than the terms we input to guide the gathering, those determined by our shifting whims and needs.

The world, we have discovered, is flat after all.

What is sober realization, what is our own exalted deflation?

It would take long catalogs to plot the movements in painting after Pollock, and this has been done. If a chart were made of them, it would show dispersion. If a demographic survey taken, diaspora. The argument between form and content was taken to its limits, by some in disjunctive juxtaposition, or to the realization there were never grounds for the debate. Artists reduced forms to their simplest expression in hard-edge shapes or diaphanous fields of color, or sharpened them for optical effect. They sounded the quiet mysteries of chance and subtle patterns, or turned themselves loose in formal chaos. Words appeared, and concepts without words or image. Or they denied the rectangular canvas was a window on anything, and they reshaped or attacked or abandoned it; brush strokes were erased or reemerged in excrescent globs. Or they returned to representation in paintings that reproduced the world exactly, without comment, or, one step removed, represented photographs of the world, revealing it to be nothing other than what it was. Or they attacked the world in sharp social comment, or they embraced all the world threw at it, its detritus and camp and kitsch and guileless self-promotion, breaking down the distinction between high and low, taking the world straight or giving it a comic side glance or setting themselves apart at a distance too rarefied to be called irony. Distinctions were made, the divisions of gender and orientation and skin color asserted. The body and its parts were reproduced in lassitude or brought to the point of excitation. Faces and questions of identity fractured into states of self-consciousness, self-absorption, self-denial, self-anesthetization, and self-annihilation.

Taken together, all the work provides a complete, accurate picture of the world and how we stand in it. There is a point that defines the dispersion and sets the tension that sustains our engagement with this art, but if you blink it is gone, you are left nowhere. I have followed a parallel course on my own in my thoughts and readings and work, and have been influenced by art’s reflections, deflections, and retreats, by its moods and arguments, becoming maddened, exhilarated, and critically refracted by turns. The temptation is to say we exhausted all the possibilities. Then again I don’t know that exhaustion wasn’t the goal. I don’t know where we are now or why we exist or what is left to create.

First Boston, in my brother’s last years, made its mark handling mergers and acquisitions, for which it received hefty fees, part of a trend at the time, the leveraging of debt with junk bonds to consolidate and restructure the corporate scene or feed corporate predatory instincts. After my brother died the rules loosened and the financial landscape changed, creating a world where neither I nor anything I have done has any value, that world moved by a spirit Alan Greenspan called irrational exuberance. There have been four major market corrections since, notably the dot-com bust, its bubble fed both by the power of and our wonder in our devices and systems. Money and art even met in mutual exchange as the rich bought art to make themselves inviolable and hip or use it as a precious tangible for speculation, of which the world is running short, and there was a boom and bust in the modern-art market as well.

First Boston also took the lead in securitizing home mortgages, and it is the housing bubble years later that most takes one’s breath for its size and complexity and rarefied thought, a creation that topped anything artists showed us. Huge pools of subprime—doubtful—home loans were bundled by the investment houses and sliced into layers, then sold off in bonds whose returns varied according to their quality and risks. Complex mathematical formulas were brought into play, but at at the core lay the assumption that housing prices would never fall. Then the loans in the lowest tranches were bundled and sliced and sold again in CDOs, collateralized debt obligations. Both passed through the rating firms with triple-A grades, those firms caught themselves in the euphoria and the pressure to show growth and profit. An instrument was also created for investors to hedge their bets, CDSs, credit-default swaps, and these were bundled too, into synthetic CDOs, bonds comprised of CDSs layered and rated like the others. The language of the terms refers to nothing any of us can recognize; trillions were invested in the devices whose value, by one casual guess, was a hundred times over the value of the loans beneath them. No one knew what lay at the bottom—all the bad loans—because there were so many and they had become obscured in the vast construction no one understood.

Dominance, the gambler’s urge, an opening for corruption—the standard accusations don’t fully explain. The creators did follow a logic of risk in their devices, which, after all, were derivatives of competition and the free spirit. But also Wall Street invested heavily itself. Major firms were leveraged out thirty times and more. My brother, in his notes, talked about the need for positioning in the financial world, and this is a powerful motive that can lead to substitutes and diversions. Maybe, as with the artists, there was the desire to see how far things could be pushed. Or maybe, like the artists, they got pushed by the world they saw before them, which they helped make, where they got caught in an endless loop. Yet there was a faith and sacrifice invested in their architecture that resembled the sacred as they built a towering glass cathedral to debt beyond imagination.

The bubble burst and the stock market collapsed, taking the economy with it. The banking system reeled. AIG, who absorbed American General, my brother’s second firm, was badly exposed to the subprime market and had to be bailed out by our government, as were the banks he studied, or the corporations who absorbed them, one to the point of insolvency, who had to be bailed out as well. Millions lost their homes.

Everything we once thought solid melted into air.

We elected a congenial man who made us feel good about ourselves and promised us a shining city on a hill, who preached the gospel of the supply side and defeated the Evil Empire.

Yet new faces have emerged with fresh menace, and wars continue to be fought on shifting sands. The market has rebounded; vast wealth remains, anxious to move again.

Perspective, concerns:

The Lord commanded us not to make unto ourselves graven images.

Andy Warhol told us we would all be world famous for fifteen minutes.

Martin Luther saw the hand of Satan, prince of the world, God of his age, in the rise of capitalism.

Gordon Gekko thrilled us when he told us greed was good.

Marx believed capitalism contained within itself the seeds of its own destruction.

Schumpeter, taking his cues from Marx, found that destruction creative, part of the cycle of economic regeneration.

Norman O. Brown, taking his cues from Freud, saw in capitalism neurosis, the indefinite deferral of our essential desires.

Freud, however, late in his career, had doubts we were going to make it anyway. Our instinct to assert ourselves—and self-destruct—he feared was greater than any reactions we might form to divert the urge, than any concessions civilization might toss us in its desperate attempts to keep us all together.

But we no longer create pictures and tell stories about what we think lies inside our individual and collective minds. Instead we make chemical adjustments, using marvelous and complex pills to enhance performance and restore balance.

For what?

Dizziness …

Perspective:

Still there is a desire for the spirit, though it comes out in odd places, out of any proportion.

Still there is the dream of political communion, though, like the City of God, it has vanished from visible form on earth.

And desire has taken wing, on its own.

Maybe we are uneasy and sense we have indulged ourselves, but just as much we have lost ourselves in the things that absorb us.

Everywhere the sense our lives are wonderful and wonderfully moving forward; everywhere our delight we are on the threshold of collapse.

Dizziness:

Dizziness is a psychophysiological state tied to confusion and the mental processes of understanding, with a possible ontological component, if it makes sense to talk about ontology. There are many variations. You have just come to grasp a basic principle, a unity that breaks down barriers between the disparate things before you, and can see it, in the totality of its relevance, racing endlessly to comprehend them. Or you see the unity, but it careens off the walls of all the things it does not comprehend and scatters everywhere beyond them, while the things it does pervade dissolve into endless nothing. Or you only see the principle but sense no walls at all, only the outlines of what you think is there, the boundless extension of their empty possibilities. Or see the mesh of possibilities in things, but not the principle that might align them, only the chance of a principle, ever endless in its evasion. Or see neither the principle nor possible connections, only endless endlessness.

In each there is the same feeling, similar to that of physical dizziness, like an irritation in the ears, a tickling of equilibrium, and it is difficult to tell whether the sensation is one of rising or falling. In each also come feelings of doubt and confidence, of anxiety and elation, but it is not clear that the dread doesn’t belong to the confidence, the transport to the doubt. With these feelings, another emotion impossible to name, diffuse yet more intense, and with its movement, a stillness, a white mist spreading in a blinding sun—

Revelation:

And lo, in heaven an open door!

Before an iridescent sky a celestial-like Being appears who is half man and half woman, whose face is kindly and open and accepting, in whose look all discord disappears. And around the Being there are seven screens, and each screen shows the Being and the seven screens, and the seven screens on the seven screens show the Being and the seven screens, and the reproduction continues as far as the eye can see, endlessly. And the face is a voice and the voice is a face, and the voice says come hither and I will show you what must take place after this.

And the Being holds in her/his left hand a scroll sealed with seven seals, and asks in a loud voice who is worthy to break the seals. A large beast who is half lion and half man, greatly maned, steps forward and roars the seven encrypted words that no one can recognize, and the scroll opens but then disappears and the screens go blank. The Lion roars again, and seven angels, young and sharp and clear, each with seven eyes and seven corporate bodies, appear and are given seven horns, and each in turn sounds her or his horn in wrathful scorn, and the screens turn on again. One shows darkness in the skies above the earth. In the next fire and cosmic rays ravage the land. In the next leaves fall from trees, in the next the land is torn by tornadoes, in the next the land is scraped clean by hurricanes. In the next social diseases infect our bodies, in the last diseases infect our systems.

Then the seven angels blow their horns together in blaring judgment and the screens dissolve into the iridescent sky, and the sky then fills with final battle. Legions of demons and the stressed and the foul in spirit, with strange faces and strange tongues, take the field, the wastelands of the world from wars past and present, to do battle against legions of angels called to duty, bright and clean, whose words are pure, and both turn loose the machines of war against the other. Great is the battle, and great is the loss of life and limb, and the field turns red with blood. And there is great respawning at points across the field as the angels and demons and foul in spirit reappear, larger, more powerful, and stranger, wielding stranger, more marvelous machines, and the two sides start to resemble each other in their fury, and they come now from beneath the world and beyond it. And the battle lasts a thousand times a thousand years, and the respawning multiplies a thousand times that, and the pile of carnage a thousand times that, and the noise of battle rises louder a thousand times that, and the two sides cannot be told apart and no words can be distinguished.

And then the sky turns to gray static and nothing can be heard.

Then the Lion appears again, standing on a rock, and proclaims the circle of life has been restored. And behind him, behind the rock, the New City appears in which glass towers in fantastic, angelic shapes soar, and beneath them there are golden arches, and the Sacred Ghost of the Brothers L, and the Virgin, and the Toys That Will Be Us. And through the city runs a river of light, an endless flow of changing colors and images and faces and words and numbers and signs. And great is the rejoicing from the multitude who have passed judgment and been saved, and their rejoicing becomes the river. And alongside the river strolls the Cowboy Who Is Naked, playing a guitar trimmed in red and white and blue, singing hakuna matata, don’t worry, be happy—

My brother spent many of his long hours fronting for First Boston with the institutional accounts, traveling widely, a source of frustration and wear. He made yearly swings out to San Francisco, and while I was at Berkeley I caught him for a few hours after the meetings, each time seeing his building exhaustion. On his last trip it seemed total, so I talked him into taking a break and driving down to Big Sur just to get away, which I needed to do myself. We went on a hike, exercise we often took in the Appalachians before he started his career, a ritual of retreat, challenge, and renewal, of ascent and a view from the top. The trail we took was fairly steep but not that long, yet, with both of us at odds with life, it taxed us. We rose from the shade of redwoods and balm of ferns alongside a creek up into hills shadeless, but for a scattering of forest oaks, and hot and windless and brown and dry, months past the renewal of winter rains. We didn’t take water. When we reached the top we were spent and sweated out, still without breeze to cool us, the smell of dried grass and scrub scratching our noses, the heat parching our dry skin and resolve. We could see for miles, but only saw the Pacific, extending out and diminishing into a glare at the horizon beneath an indifferently colored sky, that and a seemingly endless expanse of rolling hills without contrast or momentum. It is the image of California that often returns to me when its mist lifts.

The hike and view comprise another memory I want to keep now, alongside the one of our trip to the Metropolitan, both of which sustain me and remind me who and where I am. To use my brother’s death as a focus, a point of theme and exploration, would only leave me with varied stories about angles on health and life that would not tell me anything about who he was or what he would have had to have given up to survive and where that would have left him, or even if survival were possible. There is never an otherwise in such stories and they never tell me what I need to understand. Nor can I think of any stories told now where I can or want to place him. A great many of all stories told end with death. It is a way to heighten tension and give direction towards a pinnacle, the climax, but as much it is a concession that we don’t know what we are doing and can’t think of another end.

Death, of course, is an abstraction. About the thing itself we know nothing.

It is not possible to explain the void in my life left when he died and there is no point in trying. I can only attempt to get some sense of its size and maintain it. What I also remember now and want to preserve are memories of the late nights we’d spend talking about all we had seen and read, drinking, smoking, filling his apartment with a haze, adding to and trying to see through it. There are few times in my life I have felt more alive.

Autumn Rhythm:

It is not quite a web that the mesh of lines suggests, as the lines don’t always cross or connect and in places trail off by themselves. Nor a mass, though there is massing. Inasmuch as it is a web, it is not one that is attached to anything but exists in a state of suspension, by itself, separated from the edges of the painting by a rough but fairly even border of empty space, canvas without paint or primer. Inasmuch as it is a mass, if one can speak of gravity in a painting it might be said that the mass defies it. Then again, it could as easily be said that the webbing itself generates the force that gives the massing its weight and presence.

The massing, or webbing, is squarish, having about the same proportions as the rectangular frame that holds and defines the painting. Within the massing, three large areas of activity might be discerned, left, right, and center, almost equal, as if the painting is laid out in triptych form, though there is no sense of clear moments or purpose or progression among the three and none is distinct enough to imply it belongs to the large massing, or webbing, nor is the large massing definite or discrete enough itself that it might be divided, that it might posit a sense of wholeness and parts related. Within the three areas, perhaps a dozen or so smaller clusters, which, once seen, pull away from them and do not seem parts of anything but which, together, comprise the largest part of the massing, or the webbing.

Against the predominant mesh of black lines, over, sometimes under, a pattern of white lines. Thicker than the black, they contribute to the massing, but because there are fewer of them and they are spread apart and scarcely connect, they contradict the sense of webbing and clustering. Or they suggest another webbing countering the black but less complete, which, because white, seems at the front, as if caught in and trying to escape it. But it is the black that appears foremost to the eye, as if frontality is not a matter determined by light and dark. Neither mesh, however, appears to come forward or recede very far: Distance has been denied, or held in check. Yet the space seems endless.

Against the black and white lines, still contradicting the webbing but not the massing, again frontal yet receding and too close to the shade of brown of the unprimed canvas to allow an independence of hue, a scattering of thick, tan shapes like checks, largely separate from each other and in places isolated from the black and white, in others buried in them. Much fainter, fewer still, and again isolated and scattered or embedded in the white and black, a few runs, a few patches, a few specks of a grayish blue, which as much hint at color in the painting as they accentuate its monochromatic cast.

Each color—black, white, tan, gray—might suggest four different webbings, each less massive, each less complete according to the degree of its presence. Then again, the four might all be part of a larger mesh, or mass, that comprises them all and lies beyond them, if the painting encourages us to look elsewhere. But it would be difficult to decide whether that larger mesh itself moves towards some larger whole or away to a larger incompleteness. Either way, distance is still denied, or held, yet still seems endless. Depth remains suspended in endless debate.

The black lines, and to a lesser extent the white, cross the painting in broad, subtle sweeps that might be described as graceful and even approach beauty, if grace is a state than can be broad and is what a sweep of lines might carry. But they also make quick turns, coming sharply back on themselves in circular reversals that anxiously disturb the grace and the beauty. And the lines themselves sometimes lose the sense of lines, trailing off into a splay of streaks or a spray of points of accident or indecision. Or they congeal into odd-shaped blots, like nodes of swelling, which could move one to thoughts of ugliness and despair, if there is an issue of beauty and grace at stake for contrast. Which prevails, grace or anxiety, changes with every glance. Then again, grace or beauty, or both together if the two are related, may be what the painting—in its reversals, in its indecision, in its streaking, in its splattering, in its blotching—attempts most to avoid, and in doing so has been decisive. Or there may be another state involved, which has nothing to do with grace and beauty, or anxiety and despair, and the appearance of ugliness—or beauty—is only an illusion projected by the eye, unsupported.

There is a sense of movement, urgent and quick, yet light, a racing, a swirling into, through, and across largeness. But also there is congestion and collision. And to the extent each turn and each thrust counteract, there is just as much a sense of stasis, or of canceling out, or decay.

There is a sense of presence and of containment, but it’s difficult to say which contains which, the mass of the lines and shapes, the empty space of the raw canvas, and impossible to know what presence is revealed.

There is distribution and some evenness, and with the evenness and distribution a sense of patterns and patterning, of order. Yet if the patterning has any regularity, it is in the constant difference, the constant irregularity of the parts—of the length and bend of each curve and of the curving within a curve, of the size of the blots and their varied contours, of the various angles of the checks, of the varying density of each spray of dots—and in the consistently different ways the parts come together and disperse.

And there is almost a sense, in the definite existence of lines and shapes and in their definition, of figuration and of types, and of variation within types, a comprehensiveness, a comprehension. But, as with the patterning, their overall differences and total irregularity defy any figure or understanding.

The closer one looks at the whole massing, or webbing, the more one sees three areas of activity. The closer one looks at those three areas, the more one sees the clusters. The closer one looks at the clusters, the more one sees the splats, the lines, the sprays, the spots, the more one becomes aware of an unrelated gathering of unattached parts, each of which speaks with a separate, individual insistence.

The painting as much gives rise to hope—or despair—as removes the props that might support either.

We destroy ourselves when we reach beyond ourselves. We languish if we do not try.