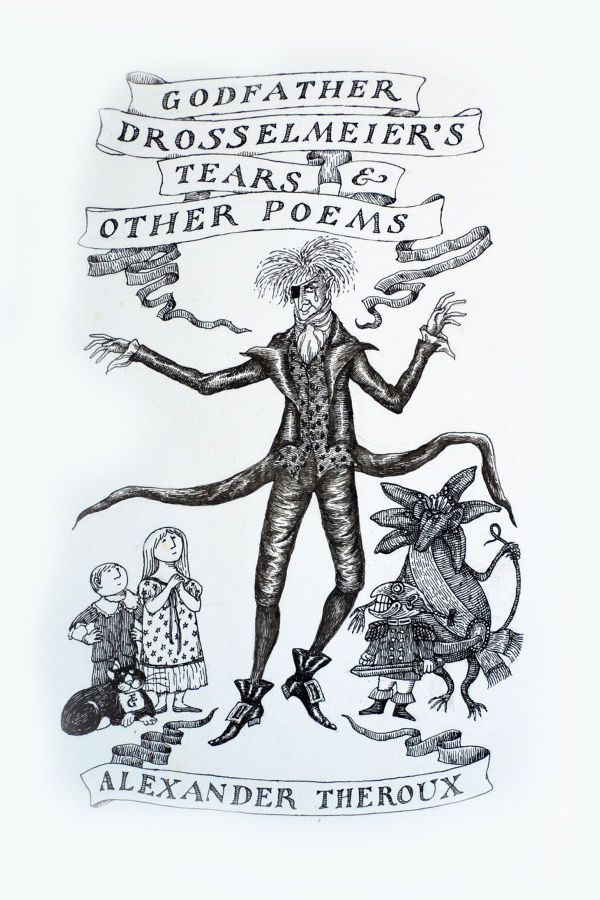

Illustration by Edward Gorey

PREFATORY NOTEConjunctions celebrates the eightieth birthday of one of America’s most distinctive writers with the first complete version of a long poem Alexander Theroux has been developing for decades. Originally intended for his unpublished Godfather Drosselmeier’s Tears and Other Poems, for which his friend Edward Gorey created the striking cover above, this Browningesque meditation is an apologia pro vita sua/ars poetica by way of E. T. A. Hoffmann’s Nutcracker fable, with Theroux in the role of the mysterious Drosselmeier. A considerably shorter version appeared in his Collected Poems in 2015, but since then Theroux has expanded it twofold as he continued to brood on his writing career, his aspirations, and his place in the literary landscape.

—Steven Moore

“But, dear God, please give me some place, no matter how small, but let me know it and keep it.”

—Flannery O’Connor, in prayer

I who knew it badly wrong to quit a venture

when it became routine knew I would do what Noël Coward would,

like any neutral, yawning Laodicean,

and so big God, tall and eye-patched to avoid

having to watch my incorrigible fears and boiseried corruptions,

disordered, corrupt, larboard-leaning,

opened no goatbag of shiny gifts to me,

lest by pride and vanity I falsify the Scriptural pages I thumbed,

no wiser than a blunt-muzzled capybara,

figuring if Absalom was the handsomest

man in the Bible I would settle to be a knave of hearts, anything

remotely blessed, a squire with fox-red hair,

say, some pomeroy in a stiff collar and tie

allowed to arrive at some small certainty, raise an eyebrow or two,

not necessarily invent the wheel,

prove, for all my workaday baseness,

that I merely be not fooled in this life, penalized by commonness,

be no feeble houseguest on this earth,

even if no apostle, a fool but a fool

to make a difference, somehow, to rise above the life I was handed,

some bravo to frivol with a little fire.

Tinfoil-hat alert: I asked God for more,

sharpening my quills and gathering reams of paper to write books

as an antidote to all I was not!

I grew up in the gabby anarchy

of a big family with lots of brothers and sisters. We fishfiddled

into our teens like common beagles,

barking for food, playing out fate,

although for all stages of amazement I fixed predominantly on

my bewildering childhood,

until I could take it no more, seeing

finally by way of my heartless siblings evil was not a problem

to be solved but a fate to be endured.

I hadn’t the privilege of certainty,

that effortless sense of privilege born out of wealth

and what is referred to as high breeding,

but convictions I had, a luminescence close

to genius, my mind no fish-paste factory with a slubbering

floor of dead smelts, cod, red porgies.

I sat in vile beuglants over notebooks,

smoked green pot for the scenic comfort of vegetable television,

and filled pages with nutty screed.

A work of art offers itself to everyone

but belongs finally to no one, according to Baudelaire. It gives

itself away indiscriminately in the way

any two-act ballet belongs to any boob

perched in any seat in any row in any theater he claims, and I

secretly hoped that art and love, partaking

of the same self-surpassing generosity

through which God gives himself to the world, might find me

worthy who would also co-create.

Wasn’t I competent enough to count,

show God I was not just another queer quidnunc in this world

a stupid chew toy, a right prat?

I who in my searches was able to discern

terpsichorean warp in a thunderstorm, scarlet-eyed cvoirths

among angels, maleks, and messengers,

sought God by joining the holy Trappists

where I made jelly, sewed chasubles, fed fat chewing sheep,

chanted under naves many a “Te Deum.”

Had I adequate faith? For St. Augustine

the recovered self is in all matters, a renewed transcended self

which explains how he could recall

his sinning self without sinning again

by his working memory. I worked to recognize the past

for continuity to some future, shining.

A river cut through every duplicity in life

that promised Jesus’s endless substitutionary love for me,

faith I have never lost or relinquished.

Inevitably, I was a recusant, defiant,

objecting to any other authority and its mutt-like face,

a credulous Papist unbudgeable.

No need in me was close to as deep

as my nightmares, making me the bed-wetter I became

who avoided waking up to reality,

diving into the depth of sleep, fleeing

what awaited me awake, accusations of me being me.

So many of the things that I ran to

were explained by the things I ran from,

my fears becoming a kleptopredator who stole my mind

and then proceeded to devour me, too

I regarded any praise as unsaid, inconfident

of my true place in life, my mind a big neep of hesitations

my wishes tall but rare as fields of blewits.

Didn’t Leonardo tell us a man could

fit inside a square and a circle both? I searched to find

where I might connect, attach, unite.

Was it so haughty of me to need

to interpret my own life as other than a formulated creature,

the product of a worthy syndrome,

lest in my own charmless eyes

I become objectionable to the very me parading the black halls

my pedestrian self walked?

I sought to write pages to be loved,

preaching through personae, rare odd multi-voiced puppetry

masks that grinned and groaned

through whatever infamy narratives

that might outlast me lest love be locked out. So was I too odd

to succeed on this scary planet?

Couldn’t others see I had a stage mind,

nearly photographic recall, selves to share? In dreams I anticipated

coming perspectives of development.

I was hurt by life into poetry and crossed

the Clopton Bridge from Medford into my own mysterious London,

the role of looker-on foreordained by fate,

although my scribblings, while never born

of a disinterested rubric, were nothing at all compared to

the acrimonious ravings of my mind, but

God-fearing, the rind of one apple tasted.

“Hang there like fruit, until the tree die!” I cried to myself,

calling from the tincture of my lurid face.

I chased my rude and raw red visions

like the Hebrew prophets did their own (or so I thought)

when the spirit of God took me by the hair

and I felt exiled, baggage on my shoulder,

my face masked, as I dug through a hole like Ezekiel

to watch through my writing no world

but creeping things, abominable beasts,

and idols, fetishes, drawn upon the walls of rooms, more

than seventy selves worshipping my art.

It was as if I had a reflection of myself,

pursuing fame, stumbling over the need but greedily to find

the face I hoped to be heroic but was vile.

Was Marx correct when he said of legal institutions

they cannot stand higher than the society that brought them forth?

I’ve always been a famous version of myself

with a word to the fates not to be a symptom

of the times I wished to transform. I saw I was a law unto myself,

not above nor below, only beyond my peers.

Who cared what kind of shirt or shouting slogan

the murdering party wears, whether it is attacking working slobs

or inbred toffee-nosed silver spoon wankstains.

Life, I saw, left me an anthropophobe,

still I insisted I be saved even if through those sins and sorrows

I abjured in and by desperate repentance

to be worthy of the God that made me

and my face and my vagrant need to expend my talent and tact.

I badly had to matter in my mind.

“Non fui, fui, non sum non curio”

read a cool Epicurean gravestone of the Roman empire,

but that was not my epitaph.

Wash myself with water as I might,

God’s plan allowed for the irrational, the discordant, and

the inexplicable. What is obedience

worth without knowledge? Adam ate

the forbidden fruit and spat out me, my face, my name, my voice

unimprovably all that I had to give.

I needed to signify, not mimic fresh snow

absorbing sound, lowering ambient noise over a landscape.

Non-persons unperson persons!

Anonymity is a kind of failure

is not a saint’s remark, and yet, although I felt ashamed

in my aspirations, ambition bit me,

for as Pelagius said, “If I ought, I can.”

Ought implies can. The free will he preached that we had

filled me with the terrible resolve

to walk through the Forest of Arden,

although I felt more a stranger there than I did at home.

But then travelers must be content,

and if I felt homesick for my real self

when among the phony mask-wearers and meat puppets

who succeeded in this farcical world,

life among the greedy ruin-bibbers

who are never, never friends of Jesus or the Holy Cross

being as sadly secular as it always is,

I prayed to re-create what God created

and tried to be as free as the Purple Martin and its song of

boisterous, throaty chirps and creaky rattles.

I determined that belief was the engine

that made perception operate, that by actively disguising

my own unhappiness I could remedy it

That there is no description of Christ

in the whole of the New Testament bade me feel I myself

may shape-shift a fit semblance,

transcending the impossible illusion

that I had to be what, when looking down at me as bloatware,

people surmised I would be nothing else.

Don what persona you will, be no fanfaroon

to falsify the basic you. Spring travels about the same rate

as a parent pushing a stroller, and I begged

my fate not unnaturally bum-rush the weather

that composed the scenery of my life. I wanted to be loyal

to God’s nature and, so, to my own.

Let no tide, neap or spring, drown me.

John Wesley’s rule was always to look a mad mob in the face,

and as I fumbled though my metaphysics

I sought identity as being, not becoming,

not jiggling pocket change in a doorway like some scarlet pimp,

nor wasting my life like a silly fandangero.

I was a born antinomian, secretly despised

restraints and rules but feared much and, like the Arabian horse,

hated a slap or a blow, regarding most insults

and other’s opinions as left unsaid, mentally

tricing them up in the rigging and taking Fate’s deserved

bitter lashes as I always walked away.

I was a criminal bed-wetter. Imagination

was my only reality, and I drove into sleep for refuge,

refusing to awake for any reason at all,

avoiding the scary parade of hideous facts

that waited to confront me whenever I awoke. Plunging

to the depths of whales into the dark benthic

became my salvation until I woke sopping wet

high tide and low, always to learn again the secret

to art is like an intrepid sailor going too far.

I have milled about with the precariat,

watching fools ambush-market their mediocrity to the world

bowing low and scraping. And me?

Art was my salvation to remake what I

in the world inherited, whether hare-drummer, Fritz, gnome,

mouse-king, or Nutcracker soldier.

I prayed I that I could signify just enough

to make heaven weep for me and my blunders. I would count

myself justified even by God’s pity.

I pled only not to be a donkeystone.

St. Augustine declared, “Love means: I want you to be!” I was—

or, I swear, at least pretended to be—

and so that gets me nothing? I who swore

I need not have been a soldier in full-parade uniform, Nutcracker cute,

expected no Clara or Marie to buss my bum.

Moses boldly killed a man, and so did David,

and the good Godfather, reaching into his grab bag of dolls and dollars,

allowed them solid profiles the world adored,

so why let the poor Gringoire I am, I asked,

be a dry ball of failure? I will play any role you offer, Councilor Grand,

let me only be a nut that cracks!