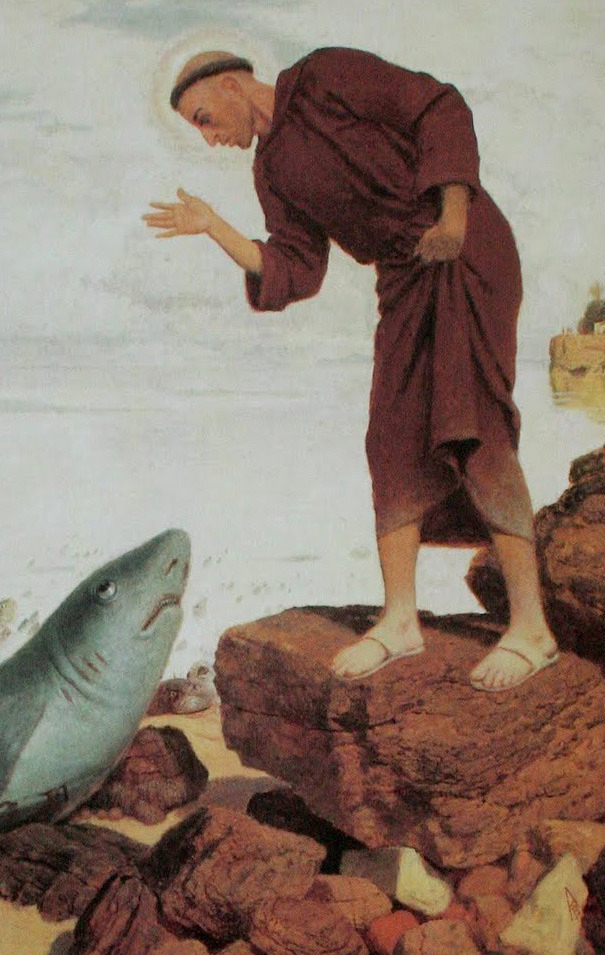

The Miracle of the Fish

The Miracle of the FishANTHONY OF PADUA (c. 1195-1231), Franciscan friar and priest. Venerated as the patron saint of lost and stolen items, he is credited with many miracles. On one occasion, the holy man went to preach in the Italian city of Rimini, which was then a hotbed of heresy. Local leaders had forbade the citizenry to pay him heed, however, and so all his attempts to lead sinners to the light of the veritable faith and the way of truth were met with silence. Frustrated by the obstinacy of the heretics, he decided to pray at a nearby place where the Marecchia River flows into the Adriatic Sea. There, inspired by God, he turned toward the water and called out, “Oh, you fish of the river and sea, hear now the Word of the Lord because the heretics do not desire to listen to it.” At once thousands of fish stuck their heads above the surface and arranged themselves in neat rows, straining to hear each one of his words.

At dawn, as police made plans to arrest Father Marek, a pilot whale washed up on a nearby beach. The priest himself was the first person to come upon the stranded animal, its sleek black skin glistening in the surf, its huge body writhing and flopping, its mouth pressed into what looked like a carefree smile.

Another passerby might have been alarmed by the discovery, but Father Marek’s whole adult life had been a series of sudden arrivals and departures. His name, for instance, was a fabrication, though he had grown to like the sound of it on parishioners’ lips. Nor was the priesthood his actual profession, though he had briefly studied at a seminary many years ago. His only occupation, one that took many forms, was convincing other people to place their trust in him. Standing over the beast while absentmindedly attempting to imitate its smile—an old habit he practiced on almost everyone he met—Father Marek thought about how much he’d enjoyed these past few months on Florida’s Treasure Coast, how he’d miss these early morning strolls on the beach, when night and day were all one thing in the purple sky before sunrise.

Coming to a new place, starting a new life, inventing a new persona—all that was easy. Father Marek just drifted ashore and let people find him, exactly as this whale had done. One day he had shown up at the local parish in his robes, claiming to be a priest who had recently retired to Florida. He carried with him a commendatory letter from the bishop of the Diocese of New Ulm, Minnesota, and a kind of clerical ID card known as a celebret. Both of these documents were forgeries, of course, but the local pastor had barely glanced at them as he welcomed Father Marek into his church. Not only did the newcomer possess an easy knowledge of the particularities of celebrating Mass—how to put on vestments correctly, for instance, or how to flip to the correct pages of the Missal—but with his unassuming manner, paunchy frame, jowly face and sad blue eyes, he had the air of someone you'd met before but couldn’t quite place, someone who was too discreet to mention your lapse. Soon he was working as a substitute, or “supply priest,” in several local parishes, celebrating Mass, hearing confessions, organizing prayer meetings, officiating at weddings and administering other sacraments, as well as selling tickets, at $4,000 per person, for a pilgrimage to the Basilica of St. Anthony in Padua, Italy.

Making people believe his fabrications—Father Marek took no great pride in this talent, which was, after all, a fairly common one. His real genius, he knew, came in recognizing when their belief began to wane. That’s what had always set him apart from other people who lived by their wits, what had kept him ahead of the law and, with the exception of seventeen unfortunate months in the Central Utah Correctional Facility, out of prison. And now, standing over the whale, he knew that unless he wanted to find himself in the same situation as that helpless animal he would once again have to flee. On the previous night, the pastor of the local parish had called to invite him for coffee at the rectory in the morning. Most priests, he’d learned, were passable liars, but on this occasion Father Marek detected too much nonchalance in the other man’s voice. Only a couple sentences into the conversation, he understood that his time here was at an end.

The whale lay on its side, staring up at him with a glassy black eye, ancient and accusatory. What was that passage from Psalms 33—the one Father Marek had used in a recent homily?

Behold, the eye of the Lord is upon those who fear him,

upon those who count on his mercy,

To deliver their soul from death

upon those who count on his mercy,

To deliver their soul from death

The priest was far beyond worrying about his soul, and he feared arrest far more than he feared God. At least $60,000 remained of the money he’d collected for the pilgrimage, more than enough to make a new start. He had spent the night packing up his few worldly possessions, scrubbing down his motel room, throwing away anything that might later be used to tie him to this town and wiping clean the hard drive of his laptop. Everything he owned was neatly packed into his car, a brand-new BMW that waited for him in the beach parking lot. To his own surprise, however, he was finding it hard to leave. It was not God’s eye he felt upon him now, but the gaze of someone who had strolled into the church a few weeks earlier, a woman whose name he had never learned, whose face he could barely remember and whose whereabouts he did not know. Nonetheless, the thought of never seeing her again made him hesitate.

The sun was bursting open, a wound in the blood-colored sky. Leaning over the whale, Father Marek saw his own shadow in its huge dark eye.

“There’s nothing I can do for you,” he said. “Please understand.”

And then he hurried off, making sure, as he always did, to let the waves lap away his footprints as he disappeared down the shore.

The Miracle of the Drowned Child

The Miracle of the Drowned ChildIn Lisbon, where the saint had received his early religious training and joined the Franciscan order, a group of boys pretending to be sailors once climbed into a boat and took it out on the waves. Suddenly, however, a violent storm broke loose, capsizing the vessel and casting the boys into the sea. All of them survived but one—a child who had not yet learned to swim. Upon hearing of the tragedy, the boy’s mother rushed to the waterfront and begged the assistance of local fishermen, who lowered their nets and hauled up the lifeless body. The father of the drowned child wanted to hold a funeral right away, but the mother refused. “Either you leave him to me,” she cried, “or you bury me with him!” Seeking out St. Anthony in tears, the desperate mother promised him that if the child was restored to her she would consecrate the boy to the Franciscan order. On the third day, her unceasing prayers were answered and the boy suddenly awoke as if from a deep sleep. When he grew up and became a Franciscan as promised, the young man took joy in telling his fellow friars how he had once drowned in the depths of the sea—and God had brought him back to life through the intercession of St. Anthony.

It was one of those form-follows-function parish churches that had popped up all over the country in the last decades of the twentieth century—bare-brick interior, fan-shaped seating configuration, no-frills altar with an abstract, bloodless Jesus on the cross. The most notable feature of the place was a series of floor-to-ceiling stained-glass windows, rendered in a cartoonish style that must have seemed very modern when the church was built in 1974. Father Marek liked to think of them as a DC Comics version of The New Testament, with Superman as Jesus and Lex Luthor as Pontius Pilate. Each window came with its own cut-glass caption in vaguely psychedelic lettering—“The Beloved Disciple,” “The Rock” (for St. Peter), “The Betrayer” (for Judas), “The Pharisees”—as if the church was a giant biblical trading-card deck.

The first time he saw her, the woman was standing in front of the window depicting Mary Magdalene. The sun poured through the glass, leaving the stranger in shadows—achromatic, a mere outline beneath the words “The Witness.” The only feature he could make out was a dazzling corona of curly silver hair, unloosed either by humidity or lack of personal care, through which the colors of the window shimmered.

It was a Tuesday afternoon. The two of them were alone in the church, thirty feet apart. The place was silent, save for the steady whisper of air-conditioning vents. Although it was nearly 100 degrees outside, Father Marek suddenly felt cold.

“May I help you?” he asked.

“Are you the priest?” replied the silhouetted figure. Even her voice seemed shadowy, full of absence.

Father Marek gestured to his collar, laughing. “Don’t I look like one?”

The newcomer said nothing. He could feel her gaze upon him.

“Perhaps,” he said, “you were expecting Father Guillermo, who is away for a meeting with the bishop. I’m the supply priest.”

He stepped toward the visitor, trying to make out her face.

“What can I do for you?” he asked.

Father Marek could now see that she was approximately his own age of 55 years. Thick but not plump, with a slumped bearing, a drawn look and that wild cloud of silver hair, she struck him as being exhausted in some deep and fundamental way. Yet her brown eyes blazed, as if backlit like the windows. In her left hand, she cupped a small glass sphere, about the size of a baseball, which also somehow seemed to glow.

“I came here,” she said, then stopped in mid-sentence and stared down at the glass object for a few seconds, before looking up at him once more. “Can you tell me about St. Anthony?”

“You’re not Catholic, I take it.”

“My mother was Jewish. But I’m nothing.”

“Well,” he said, “Anthony of Padua is the patron saint of lost things.”

Her eyes seemed to flare, but for a few seconds she was silent.

“Do you believe in miracles?” she finally asked.

“If I didn’t believe in miracles,” he said, “I guess I wouldn’t be much of a priest.”

He forced a laugh. She eyed him intently. In the cold of that room, the air thick with the smell of incense and new carpeting, he suddenly felt found out, seen.

“How do you know when it happens?” she said. “A miracle.”

He glanced past her at the stained-glass image of a muscular Mary Magdalene, crouched before the Risen Christ like Wonder Woman ready to spring into action. During his Catholic-school upbringing, Father Marek had been taught that Mary Magdalene was a prostitute, but later, when he was studying to be a priest, he discovered that this detail of her life could be found nowhere in the Bible. It was just a story some pope had made up in the Middle Ages. And no one knew better than Father Marek that if you tell a story enough times with enough conviction, people are likely to believe it. Since coming to Florida, for instance, he’d been confiding to certain parishioners that, in addition to his pastoral duties, he was writing a book, The Complete Miracles of St. Anthony: Definitive Edition with Previously Unpublished Material. Such artifacts were important in his line of work. Like relics in the Catholic Church, they made even the most outlandish claims seem credible. That’s why he’d pieced together more than 200 typewritten pages of his nonexistent manuscript, which mostly consisted of stories copied from the internet or lifted from other books but also included miracles Father Marek had fabricated for his own amusement. If someone was on the fence about whether to shell out $4,000 for the pilgrimage, he’d usher that person aside and take out the book, which he would describe in hushed tones as his life’s work. Then, after pledging the person to secrecy, he’d announce that at an obscure church archive in Padua, he had discovered a treasure trove of documents, including a beautifully illuminated manuscript from the 14th Century, containing lost accounts of St. Anthony’s miracles—miracles even more astonishing than any already known.

“Miracles,” he told the woman, “are by their very nature difficult to describe.”

“But isn’t there some way of knowing? A sign?”

Many years of experience had taught Father Marek that the desire for miracles often made people even more vulnerable than the desire for money. But this woman, whose sad eyes studied him so intently, seemed somehow beyond his powers.

“Why do you ask these things?” he said.

She stared at him, then gazed down once more at that little glass object, as if it were a crystal ball in which she was searching for a clue. For an instant, he thought she might turn and leave—a possibility that, to his surprise, made him bristle with regret. But then, with the grim resignation of someone who must leap from the window of a burning house, she threw herself into a story. In a breathless flurry of words, she told him how twenty years ago her son had vanished from a nearby beach while surfing, how no clues had ever been found, how she and her husband had begun returning every year, how they’d spent more than a decade collecting objects from the surf, bringing them back home to Michigan, studying them, arranging them in different configurations, as if those random bits of wreckage were the untranslated hieroglyphs of some secret language that might help them understand their loss. “It was insanity,” she said. “We knew that from the start, but it took years to stop. We finally managed to promise each other that we’d never come back here, that we’d put the place out of our minds.”

“And now?” he said.

“My husband died two months ago,” she replied. “And somehow with him gone, I couldn’t stop myself. I’ve been roaming the beach for these last three days.”

“And you found something, I suppose,” he said. “Something miraculous.”

His sudden contempt for her was comforting—the familiar mix of disgust and disdain that he always felt for those who allow themselves to be deceived. For a moment, it seemed that the strange anxiety he’d been experiencing ever since she arrived was at last lifting. Then she held out the glass ball.

Taking it in his hands, he saw that it was something like a snow globe, only without the snow. On its base were the words “St. Anthony.” Holding the object up to the stained glass, which gave it an oddly bluish glow, Father Marek saw that it held a figurine—a man with tonsure haircut and the brown habit of a Franciscan friar. Striding through the murky fluid inside the globe, as if making his way back to shore, the tiny saint was holding a child.

Taking it in his hands, he saw that it was something like a snow globe, only without the snow. On its base were the words “St. Anthony.” Holding the object up to the stained glass, which gave it an oddly bluish glow, Father Marek saw that it held a figurine—a man with tonsure haircut and the brown habit of a Franciscan friar. Striding through the murky fluid inside the globe, as if making his way back to shore, the tiny saint was holding a child. With a hushed sputter, the air conditioning went silent. Not wanting to meet the woman’s eyes, Father Marek studied the sphere for a long time in that still room. What were the odds that such a fragile antique would survive the ravages of the sea? A pair of unsettling possibilities—that something other than happenstance had brought this object to the beach, and that something other than happenstance had brought this woman to his church— shot through his mind. Then came an even more troubling thought—that the woman had fabricated the story for her own aims, as yet unclear, and that she was now roping in Father Marek, not the other way around.

With a hushed sputter, the air conditioning went silent. Not wanting to meet the woman’s eyes, Father Marek studied the sphere for a long time in that still room. What were the odds that such a fragile antique would survive the ravages of the sea? A pair of unsettling possibilities—that something other than happenstance had brought this object to the beach, and that something other than happenstance had brought this woman to his church— shot through his mind. Then came an even more troubling thought—that the woman had fabricated the story for her own aims, as yet unclear, and that she was now roping in Father Marek, not the other way around.“By a curious coincidence,” he finally said, “I happen to be organizing a pilgrimage to St. Anthony’s holy shrine in Italy.”

She was still staring at him, unblinking, her face intense, indecipherable.

“I have some pamphlets in my office,” he said. “Let me get you one.”

But when he came back, she was gone.

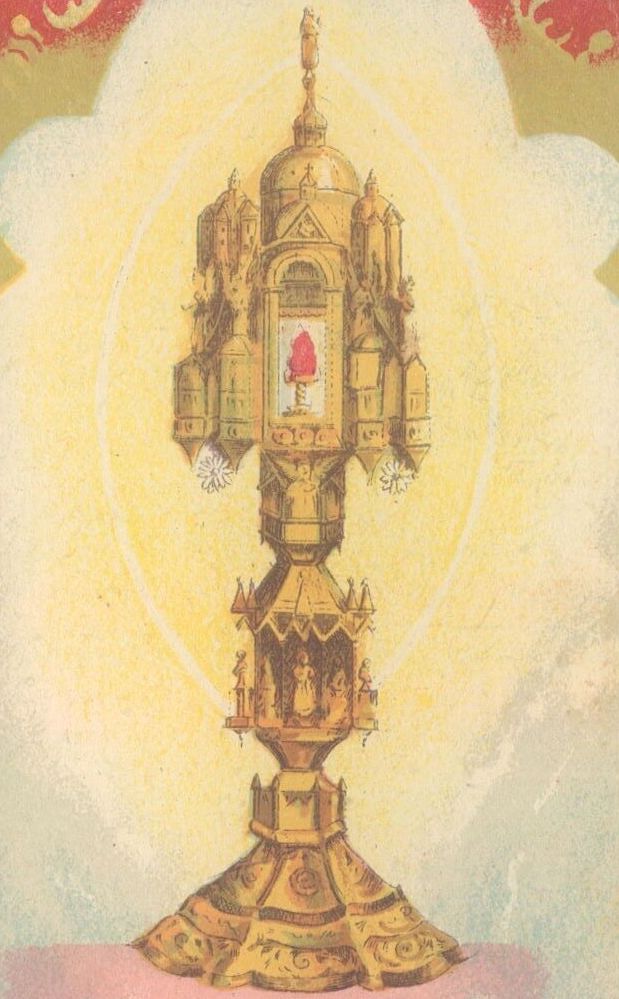

The Miracle of the Tongue

The Miracle of the TongueMoments before he was taken from the world at age thirty-six, St. Anthony was heard to say, “I see the Lord.” It is recorded that at the precise moment of his death on June 13, 1231, children spontaneously ran into the streets weeping and church bells rang of their own accord. When his body was exhumed thirty-two years later, it was found to be entirely decomposed except for the tongue, which was still “beautiful, fresh and ruby red,” according to one eye-witness. This divine favor, it is believed, was a sign from God to let future generations know that St. Anthony never once failed to speak the truth.

After departing from the whale, Father Marek continued down the shore, pants rolled up, wingtip shoes dangling from one hand, bare feet slapping at the surf, thoughts racing. He’d always been as amorphous as the ocean, adapting himself to the peculiar shapes of other people’s dreams, and when the time came he would simply wash away, a wave sliding under the surface, nothing in its wake but a fleeting shimmer. Now it was time to disappear once more—his escape from arrest, he knew, depended on decisive action—yet he couldn’t quite resist a few more minutes by the sea. Glancing back at that stranded beast, he made a bargain with himself. Whenever it disappeared from view, he would rush to his car and drive away forever. But every time he turned around, he could still see its silhouette, not much smaller than the last time he’d looked. Wondering if it was an optical illusion, he cupped both hands around his eyes to block the rising sun and squinted up the waterline. The whale was still in sight, shining like a black glass bead, though it no longer seemed to be moving. Had it died in those few minutes since he left? Father Marek remembered a video he had once seen—the carcass of a sperm whale suddenly exploding due to a buildup of methane gas from the decomposition of its internal organs. The skin ripping open, the guts blasting out, the blood cascading from inside like a crashing wave—even now, the thought of it filled him with revulsion. Ever since he could remember, he’d been disgusted by body parts, blood, entrails—things that should be kept internal and intact, separate from the exterior self.

Back in seminary, he’d traveled with a group of fellow students from Chicago to Italy to see the preserved tongue of St. Anthony—an experience that caused him to abandon plans for the priesthood. February 15, 1981: He recalled the exact date because he was one of thousands of devotees in Padua that day for the Feast of the Translation of the Saint’s Relics, commonly known as the Feast of the Tongue. What he remembered about the chapel all these years later were the dozens of white marble angels, gaudy fantasies of the baroque period, frolicking playfully above the main altar. He remembered the smirks on their faces, as if they were staring down with contempt at the endless line of gullible humans waiting to venerate the tongue. He remembered his own revulsion at being brushed against and breathed upon by his fellow pilgrims, his disgust with the sickly smells of their perfumes and colognes, the cigarette smoke in their clothes, the stink of their unwashed bodies, the desperate hopes and fears that seemed to rise out of them like the bacterial reek of a putrid wound. He remembered their ridiculous carryings-on at the ornate gold case in which the tongue was housed—the tears and prayers and signings of the cross, the kissing and touching of the glass cabinet containing the reliquary, the whispering and moaning and comically exaggerated gesturing. And, of course, he remembered his own encounter with the tongue—how it had seemed like nothing more than a triangular glob of pickled grey flesh, how it had left him empty of emotion, how it had given him no comfort, only a furious surge of nausea, and how, catching the sight of his own reflection in that filthy glass cabinet, he had realized he wore the same sneering grin as those marble angels overhead. And it was then that he knew the truth—not just that he could not be a priest, but that being a priest was the most pathetic and preposterous thing he could ever dream of becoming.

He’d felt dizzy, stomach acid swelling in his throat. Near the altar was a spot where pilgrims could write prayers to St. Anthony and stuff them in a box. Almost instinctively, Father Marek reached into his breast pocket and pulled out something he’d scribbled on a piece of hotel stationary that morning. Then he hesitated. What was the use? Why even bother going through the motions? A line formed behind him, fellow worshippers staring at him and whispering angrily in various languages. Stifling the urge to throw up, he slid the note into the slot.

O Holy St. Anthony gentlest of Saints, your love for God and charity for His creatures, made you worthy, when on earth, to possess miraculous powers. Encouraged by this thought, I implore you to help me find my father, Steven Dabrowski Sr., who abandoned my mother in Chicago when I was seven years old and has never returned or attempted to contact me, his only child.

O gentle and loving St. Anthony, whose heart was ever full of human sympathy, whisper my petition into the ears of the sweet Infant Jesus, who loved to be folded in your arms. The gratitude of my heart will ever be yours. Amen.

O gentle and loving St. Anthony, whose heart was ever full of human sympathy, whisper my petition into the ears of the sweet Infant Jesus, who loved to be folded in your arms. The gratitude of my heart will ever be yours. Amen.

Fifteen years later, Father Marek would solve the mystery of his biological father—not through the intercession of St. Anthony, nor through any of his usual clandestine means, but through one of those new genealogy databases that appeared in the mid-1990s. It was all too easy. Set up an account, type in your name and date of birth, and learn that the man you’ve been seeking your whole life is dead. Search the database some more and discover that after abandoning you and your mom, he moved ninety miles north to Milwaukee, where he got work as a machinist, the same job he’d had in Chicago. Do a few additional internet searches and find out he served three years for forgery in a check-fraud scheme, drifted in and out of at least two other marriages, and had one additional child, a son two years younger than you. Send that half-brother an e-mail, asking him if he wants to meet to talk about the old man. When he doesn’t respond, steal his identity and purchase several expensive suits on his credit card.

Turning anger into opportunity—that was Father Marek’s secret to success. While other people wallowed in unpleasant feelings, he transformed them into hard cash. Take that long-ago debacle in Italy, for example. Disagreeable as it may have been at the time, the experience had nonetheless provided him with the know-how needed to convince more than forty parishioners that he would arrange every small detail of their pilgrimage—roundtrip airfare to Padua, lodging at the Hotel Donatello on Via Del Santo, a private tour of the Basilica with Father Marek’s good friend, the nonexistent Friar Mario Segreti, and, for a select few, a glimpse of that rare illuminated manuscript containing lost miracles of St. Anthony—all in return for an affordable flat-rate fee, payable by cash, check, crypto or direct deposit to the priest’s checking account.

Incarnare: Latin for “to make flesh.” Father Marek had read somewhere that a person’s body contains about 20 different chemical elements, the products of supernova explosions that scattered ancient stars. But the human husk—that wasn’t formed from oxygen, carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, all those meaningless atoms, but from words. That’s how he had reincarnated himself over and over—telling stories that others believed, wanted to believe, needed to believe in order to justify their own stories, make their own flesh. During decades of shifting personas—financial consultant, IRS agent, attorney, dealer of rare coins, cancer researcher, decorated war veteran, English professor, priest—Father Marek had begun to take for granted that his whole being consisted of words, that he was more or less incorporeal. And so, in the days after his encounter with that woman at the church, it was disconcerting to find himself full of weight and sensation, pained by an ache he couldn’t quite name, or perhaps not an ache but a kind of constant rawness, or perhaps not either of those things but a sensation of being exposed.

Yes, exposed, like St. Anthony’s tongue in its glass display case—when Father Marek had stood before the congregation five days after the woman’s sudden appearance, he found himself fumbling for words, forgetting the order of things, feeling at a loss about how to look and act. Glancing up from his homily, he thought he saw her standing at the back of the church, her hair filled with light, her face lost in darkness, but when he blinked she was gone. There and not there—an apparition. The Complete Miracles of St. Anthony was full of such phantoms—a dead man who came back to life to identify his murderer; the Baby Jesus who suddenly appeared in the saint’s arms; the saint himself who more than 400 years after his own death showed up in the little Polish village of Radecznica to request that a shrine be built on a nearby hill. There and not there—hadn’t that always been Father Marek’s own power over everyone else? So why was he suddenly the one haunted by these visions? There and not there in the church, there and not there as he lay sleepless in his empty and silent motel room, there and not there as she slowly turned to him on this beach, her feet ankle-deep in the surf, her face still in shadows—and then she reached out to him and then she vanished once more, just another inexplicable hallucination, the result, perhaps, of the stress and confusion of his unplanned departure. Breathless, he wheeled to look for the whale, half expecting it to be gone, too, but there it was, shimmering in the distance like a phantasm from some dream, some mystical reverie, some confidence trick of the mind.

The Miracle of the Lost Coin

In 1621, a Bavarian nobleman, traveling from Warsaw to Ingolstadt, rested for the evening in the city of Pilsen, where, during a long night of carousing, he misplaced a gift he had just received from Sigismund III Vasa, King of Poland—a gold coin worth the astonishing sum of 100 ducats. The innkeeper urged him to seek the assistance of St. Anthony by having a mass said at the nearby Franciscan church, but the nobleman ignored this plea. For three days and three nights, he searched desperately for the coin, a fantastic rarity minted specially to mark the Catholic victory over the infidel Turks at the Battle of Chocim, where thousands of heretics were slaughtered. At last, the despondent traveler abandoned his efforts and left the city, never to return. As the years wore on, he grew more and more embittered until at last his faith waned entirely. By the time his travels took him to Padua, he was an old man. While touring the town, he heard so much about the miracles of Saint Anthony that he decided to visit the renowned “Basilica del Santo.” Simple curiosity took him through those doors, but once inside he found himself standing in the chapel under which the holy body of the saint lay, which caused him to reflect on the necessity of saving his own soul. Repenting his past apostasy, he left the sanctuary in a kind of trance and began wandering the streets. Many hours passed. At dusk, on a little-traversed passageway near the city wall, he noticed a glimmer at his feet. Wedged between two cobblestones was the same coin he had lost in Pilsen—one of only ten ever minted.

Father Marek had made up “The Miracle of the Lost Coin” as a kind of inside joke that only he and his past selves would understand. He’d learned about King Sigismund’s 100-ducat piece—one of the rarest and most valuable ever minted in history—during his days as a cigar-smoking, Brooks Brothers-wearing numismatic dealer who convinced dozens of collectors across the country to wire him money, promising them an inside line on obtaining gold coins below market value. That particular chapter in his life, alas, had come to an abrupt end just before the completion of an extremely lucrative transaction. And while Father Marek was relieved to have once again slipped away just before the authorities closed in, the thought of leaving so much money on the table had irritated him ever since—thus, the “lost coin” of his parable.

But what came to mind now, as he stumbled up that beach, was not the glistening coin but the man wandering in a trance. Yes, trance. What else to call this confusion, this indecision, this undoing of time? Although he knew better than to be swept up in his own fictions, least of all one he’d made up on a lark after several glasses of scotch, Father Marek couldn’t shake the idea that “The Miracle of the Lost Coin” somehow foretold his own fate. Not that he repented. No, never. To repent would be to look back, and to look back would be to lose his gift for reincarnation. All the same, he couldn’t help feeling a sense of rupture, almost imperceptible, a door opening faintly somewhere, an unfamiliar emotion sweeping in, something like hope but also something like remorse. And standing at that door was the woman with wild silver hair.

There and not there and then there again. At the church two days earlier, she’d suddenly reappeared a few feet from him.

“How,” she asked, “do I go about making a confession?”

They were standing in the vestibule, its walls lined with stained-glass windows depicting the Parables of Jesus. Just over her shoulder was “The Anointer,” a woman crouched next to the seated Jesus as she washed his feet. Father Marek studied his visitor. She looked tired, haggard, a defeated woman on the downside of middle age, yet suddenly he wanted to reach out and caress her face. Such an unfamiliar desire, so different from his hunger for prostitutes or his hunger for people with possessions he might make his own—for an instant, he was tempted to come clean, reveal that he was not what he appeared to be. Instead, he led her to the confessional, showed her how to make the sign of the cross and taught her to say, “Bless me, Father, for I have sinned.”

Kneeling in the booth next to him, she was silent for a long time. Then she leaned over and took something out of her purse.

“To love the child who is gone and feel nothing for the one who is there—surely that must be unforgivable in the eyes of God,” she said.

She was now cupping something in her hands, something that gave off a dull glow—the glass ball she had brought to the church during her last visit. Choosing her words slowly, she seemed to be speaking less to him than to the tiny figure inside the globe.

“I have a daughter,” she said. “She was only nine when my boy vanished. Blameless, perfectly blameless. She wasn’t even there. I haven’t spoken to her in at least a year. She’s in New Orleans; I’m not sure I even have an address. Her 24th birthday was two months back. My fault, the whole thing. This won’t make sense to you, but since the day he disappeared, I’ve been stuck on an endless shore. Out in the water—that’s his world, and it’s like he’s still out there, waiting for me. I can’t abandon him, can’t turn away and go back to the other place.”

Father Marek remembered a story, famous in his line of work, about a psychic who once convinced a grieving mother to turn over $17 million by promising to transfer the soul of her dead son into another boy’s body. Such a stupid woman, so deserving of her fate. He wanted to feel the same contempt for the person kneeling next to him but couldn’t, wanted to console her but didn’t know how, wanted to speak to her but had no words, wanted to have a small fraction of her faith in God, or in the ocean, or in whatever it was that she thought was sending her messages, wanted to want anything on earth as much as she wanted to be with her dead son. She drew a long breath and told him that many years ago she’d wandered into the sea one morning with no intention of turning back. It was a foggy day, she said, the kind when water and land are hard to tell apart, which somehow made it seem easier to finally leave one for the other.

“I kept walking until I was totally, you know, beneath. My husband was in a panic on the shore, shouting my name. But that’s not what stopped me.”

“What was it, then?” Father Marek heard himself saying.

She studied the glass ball.

“Something happened, I don't know. A revelation, I guess you’d call it.”

“Revelation?”

“Yes,” she said, staring into the globe. “I thought that if my son needed me, he’d send me a sign. One that couldn’t be mistaken.”

Father Marek imagined himself running through the surf in a fog, wrapping his arms around her waist, pulling her from the waves.

“What do we do now?” she said.

“Now?”

“In the confession. What comes next?”

His mind raced through the order of the sacrament—penance, contrition, absolution—but he couldn’t remember the words for any of it. He found himself whispering, “Come away with me. Join me on my pilgrimage.”

“What are you saying?”

“We’ll go to Italy,” he said. “Don’t let money be an obstacle. I’ll take care of everything. We’ll visit the Basilica of St. Anthony and pray for the lost.”

“No. Impossible. I don’t understand.”

“But don’t you see? It’s God’s wish. That’s why you found that thing on the beach. That’s the meaning in all this. You’re being called to St. Anthony’s shrine.”

She did not speak, did not move, did not even seem to breathe.

“No,” she replied at last. “That’s not where I’m being called.”

Putting the glass ball back into her purse, she said nothing. Through the latticework of the grille, he watched her leave, a silhouette slowly losing form, a wave folding itself into the sea.

The Miracle of Her

The Miracle of HerDuring his sojourn at the Franciscan monastery at Montpellier, St. Anthony was visited by a man who had led a very bad and profligate life. Throwing himself at Anthony’s feet, the stranger begged to be reunited with a woman whom he had once seen praying in a church. When the saint inquired about why this sinner

He never finished writing that last miracle. Time was running out and he couldn’t find the words. Why had he wasted his last few minutes at the motel trying to figure out how the parable would end? And why was he still on this beach now, knowing that each second of delay lessened his chances of escape? He felt he had been here for hours, the waves lulling him into a stupor. Looking back, he saw that whale was still there, a radiant object in the distance. And then, turning and glancing ahead again, he noticed another radiant object.

A glass ball. Or something that looked like a glass ball—a bottle, maybe, catching the light at an odd angle. He took a couple of steps, stopped, watched it dazzle in the surf, a light so intense it brought to mind that passage from Ezekiel when the prophet sees a ball of fire with “a brilliance like that of amber” before hearing the voice of God. Father Marek scanned the water, half-expecting to spot the woman, waist-deep, glancing back before disappearing beneath the waves. Picturing a corpse on the beach, just around the next curve, he felt a shudder of revulsion or perhaps of fear. But maybe she hadn’t gone through with it. Maybe she was still alive. Maybe he could find her. And then he was running—not toward the shiny thing but in the other direction, tossing off his shoes as he hurried up the shore, already winded, already soaked with sweat. He felt heavy and weightless at once, as if his legs were filled with sand, his feet only touching the ground every few steps. Suddenly, he found himself standing over the whale.

Still on its side, the beast lay still, its eye now shut. “I’m sorry,” Father Marek said, gasping for breath as he leaned over the body. “There was really nothing I could do.” And then he had his hands out to push, not knowing why, but pushing with all his strength. The whale didn’t move, didn’t stir. He felt certain it was dead, but he kept pushing anyway, determined to reunite it with the ocean. Such an absurdity. Such a useless, comical waste of time, but he didn’t stop, couldn’t stop. Tearing off his shirt, he tried to wrap his arms around the whale, lowering his shoulder into its cool skin and pushing furiously, grunting and screaming until his feet slipped in the sand and he fell to his knees, landing face first on the beast’s bulbous head. Suddenly, the eye blinked open, a glassy black globe inside of which blazed a rectangle of golden light. And inside that gleam, Father Marek could barely make out the reflection of a man, stooped like a humble penitent in prayer, the sound of a distant police siren drifting across the beach.

Images used in this story, in order of appearance: The Sermon of Antonius, 1892, Arnold Böcklin; The Drowned Child Restored to Life, c. 1505, Gerard David (Courtesy of the Toledo Museum, Purchased with funds from the Libbey Endowment, Gift of Edward Drummond Libbey); Reliquary of the Incorrupt Tongue of St. Anthony; Polish 50-ducat gold piece, 1621, minted by Sigismund III Vasa; and The Penitent Magdalen, c.1670, Carlo Dolci (Courtesy of the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA). The author would also like to thank Azize Harvey for her image manipulation of the St. Anthony globe photographs and Clare Shearer for her graphic design, not to mention her patience.