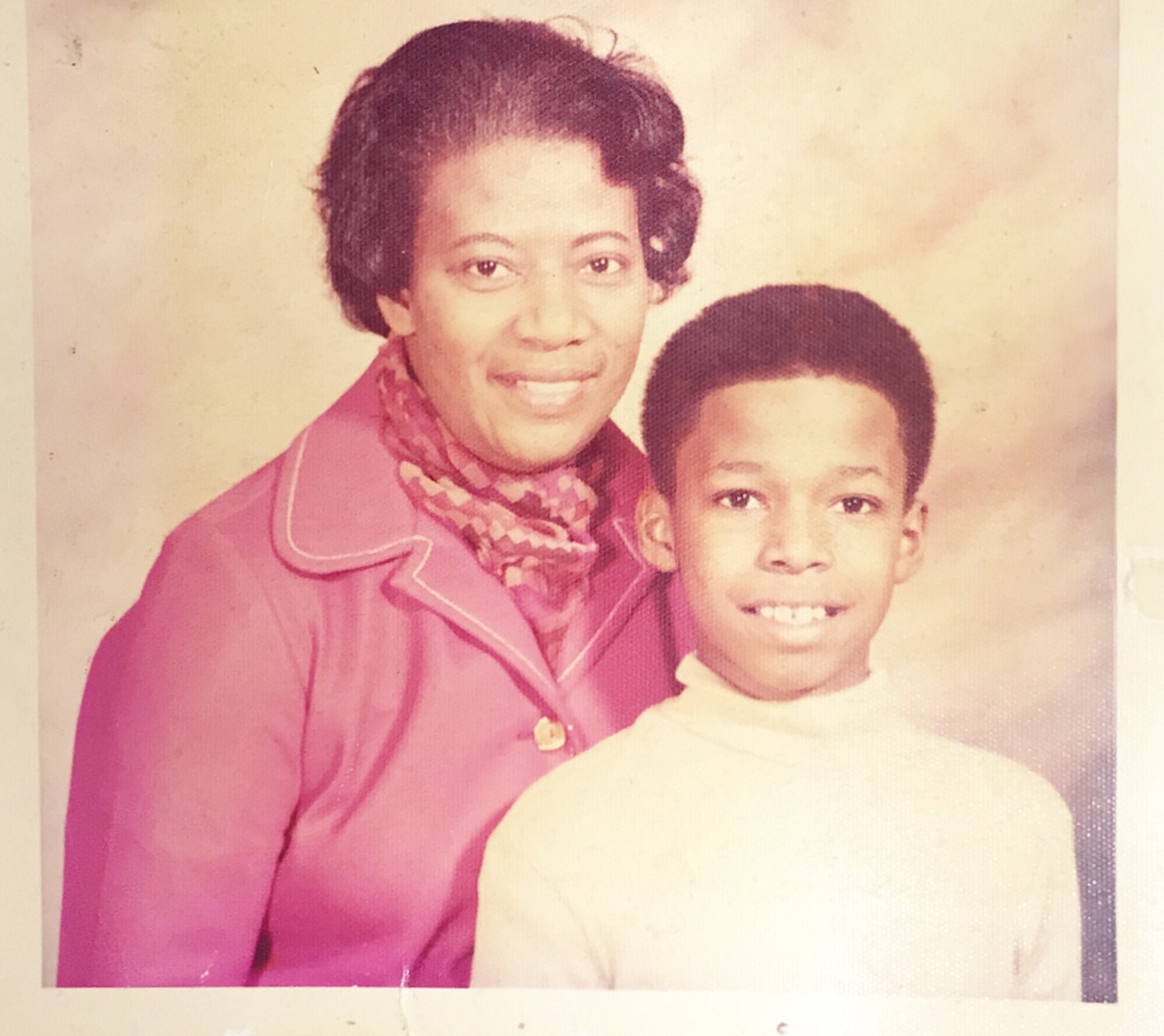

My mother urged me to calm myself—“Jeffery, they’re just insects. They won’t harm you”—for excitement had crept into my voice and face, but unlike my mother who’d grown up in the South, I was a city kid, apart from nature with its exotic inhabitants. I was struck by the clarity with which I could identify my own reflection in the dark center of my mother’s eye; how easily I recognized the fear there. I jerked my head up, blinking in the sunlight, drumming up courage. I could do it. Crouching, I danced a little nearer to the Gluckman’s house, a few steps, then another few, ready for more. Hardly to be heard in the insect uproar came another sound, a low beating that halted my advance.

I stood and watched the cicadas with a child’s rage and hate. I had just turned eleven. I was an adolescent who possessed a certain clear sentience, a boy moved by a depth of passion—for equality, for fairness, for justice—unlikely to be found in the average child of like age. Outraged that we had to withstand this invasion of cicadas that had been underground for seventeen years, biding their time. The audacity. Noticing my dilemma, my mother took my hand and started leading me to the door of the Gluckman’s house. We moved as if through a minefield—tiny explosions, crunches under my feet, feeling their residue under my sneakers.

The great yard that covered three sides of the house always gave me a feeling of vastness. The quiet, green nature-fragrant block was so different from the conglomeration of courtyard buildings where we lived in South Shore. The light seemed to lay about the massive two-story house and washed the street in watercolor tints. I was a city dweller, accustomed to urban bustle, familiar with concrete pavements, but in Winnetka I always thought I could be a lover of the earth: the quiet, the tranquility, the sense of peace that spoke from every room of the house, from the large plot of well-tended grass, and from the tall trees with dozens of branches. The pungent smell of earth. The green of the grass and leaves intensified by the clarity of the clean blue sky and the pristine definition of the white clouds. I felt a pastoral serenity that communicated itself to me through the lazy drone of the bees working the patches of flowers in the enclosed pen next to the garage. Fearless, I would step on and smash the low-flying creatures that moved slow as if in a spell.

Enjoining me to wipe my feet on the mat, my mother unlocked the door that opened into the kitchen. I have no memories of her ever using the front door. Mrs. Gluckman was standing on the far side of the room next to a counter, near the entrance to the basement. A sizeable woman, big-boned, big face, full shoulders, full hips, she presented a handsome figure in a knee-length dress, bare legs showing, her hair hanging free about her shoulders, a quiet professional. Both she and her psychiatrist husband, Dr. Gluckman, had a few years on my mother, their hair already touched with gray. For all the space Mrs. Gluckman took up in the world, she was a woman of gentle bearing, curious about life and herself, taken up with catholic pursuits, given to diving into unexplored realms of study. She held a graduate degree in social work, swam, took art classes and other classes at Northwestern. I still own a watercolor of a seascape that she painted and presented as a gift to my mother.

A smile, both spontaneous and disarming, broke across her face. “Jeffery, how is your summer going?” she asked conversationally. Her voice always sounded weak, as if she were straining. I spoke some quick response. She continued to question me out of, I decided, a sympathetic interest in my life. But I was shy around adults and strangers and felt ill at ease. Lucky for me, she seemed to sense my feeling of awkwardness and kept up an easy line of conversation that was designed to make me less self-conscious.

I made myself inconspicuous and walked discreetly past her. Once in the basement, I flew in excitement to a stack of paperbacks, one of many. An avid consumer of commercial fiction, Mrs. Gluckman placed the perused titles in the basement, an assortment I could choose from and even take home. I felt quite select in the company of books, enjoyed nothing more than reading, being transported to another place, withdrawn into another world, rapt in some kind of reverie. I had a singleness, a quality of being by myself—an only child—and for all my apparent playfulness, I preferred to keep to myself and read as opposed to spending time with other children.

I had plenty of time, did not hurry. Soon had a substantial wedge of paper in my right hand. Luminous pages. Gradually my feelings of fear and rage sank. After an hour or two, I put the book aside then spent some time drawing, making sketches of the cicadas. The activity was more than a whim. I was talented, an artist in the making. This I knew. (It occurred to me that the Chicago Picasso sculpture was neither a woman nor a bird nor a fly, as many thought, but a giant cicada.)

My mother called me upstairs for lunch. Once in the kitchen, I took a seat at the table in the corner. She moved quietly about the room. Only by the careful way in which she did things—laying the table, cutting my sandwich in half, pouring me a glass of pop and putting it in place—could it be told how much she had missed my presence. She sat down. We ate in silence, though I was sensitive to having her opposite me. I watched her face and work-hardened hands, and I wished I could share her troubles to lighten them.

A fast eater, I finished my meal before she completed hers. Popped up from the table ready to engage. Although it was cozy, comfortable, and well used, I avoided the sitting room where Mrs. Gluckman was now watching the Watergate hearings on TV. If the functional character of the sitting room and kitchen said much about the family, the other rooms told more. The dining area featured a distinguished grandfather clock with a delicate chime and a glossy polished table that could seat twelve. The parlor was always bright with sunshine, a warm gaiety and vividness, and full of the objects that bring a room alive, give it its character. I would try riffs and chords on the piano, the notes instilling a forced life in the space, my reflection mirrored in the polished wood. My eyes were attracted to the brickwork on the chimney, carefully executed masonry that spoke to me for some reason, the pattern, the stones set in perfect alignment, the precision, the coloring, the beauty. French doors opened into the sitting room which was adjacent to the sunporch, a place for relaxation outfitted with wrought iron furniture and a glass-topped table that I was particularly fond of.

Where should I go in the house? Wanted to, needed to, avoid the Gluckmans. The desire to be alone had never pulled at me so powerfully. The upper level of the home consisted of four bedrooms and an office. The largest, the master, a crisp off-white space of agreeable proportions boasting a jumbo-sized, un-postered bed with a headboard that had aged to a fine patina and large windows overlooking the front lawn on one side and the sunporch on the other. A second fireplace bespoke a cozy elegance. The room had a serene but modern feel to it, an aesthetic characterized by a sleek dresser on thin legs, a style of furniture I would later associate with Bauhaus.

Dr. Gluckman’s office seemed to be a counterpart to the master bedroom in its clean spare look. I took a seat in the leather chair behind a large comfortable desk, bare but for several pipes lined up in a rack. A faint aroma of smoking tobacco arose from the pages of the books that took up the wall behind the chair. Previously, I had purloined a copy of Sigmund Freud’s The Problem of Anxiety—small, slim, dark covered, no dustjacket—a wasted effort given that I couldn’t make heads or tails of the volume.

Dr. Gluckman never gave any indication that he missed the book. Nevertheless, I feared he could read my guilt on my face. As is, I always found him somewhat intimidating, an odd little tension, and in his presence would comb my mind for a suitable subject of conversation. Small talk. (What’s the difference between a psychiatrist and a psychologist?) He always had a smile in his eyes, a look of amusement, curiosity. Proud bearing, full of assurance, he never gave the impression of being casual, always formal, thought out. Although of average height, because of his slight build, he seemed small for a man—I was already as tall as he was. In my memory, Mrs. Gluckman stood above us both. His presence was quiet, almost like a vacancy. I could imagine him listening to his patients, his egg-shaped head and the bushy mustache placed on his face that seemed to move around on its own, Mr. Potato Head. He was very still, nearly null, in his manner, apart and watchful.

Despite their social standing, Dr. and Mrs. Gluckman were not given to lavish displays of wealth: no luxury items, expensive cars, high-end clothing. My mother had worked as their maid for a decade already and would go on to work for them for another twenty years. Be that as it may, I suspect we did not weigh on their scale. Generous where they intended to be generous, they helped my mother with loans on a few occasions when money was desperate, loans they in time told her she needn’t pay back.

Their gestures of kindness were enough for my mother but not enough for me. Two years earlier, I had stolen a toy from their youngest child, Gordy, who was near me in age. Gordy and I had been playing with Hot Wheels cars on the sunporch, making engine sounds, revving up, accelerating, crashing vehicles, pretending to repair them, the brightness of the sun making us feel adventurous and happy. He was athletic, already an expert swimmer, where I was cerebral. My mother was fond of telling the story about how, when he was barely old enough to walk, he had climbed atop the refrigerator. (“Scared the bejesus out of me,” my mother would say.)

A description not hard to picture that day on the sunporch, a little appliance climber with great bands of brown hair and color in his cheeks. Although I owned an impressive collection of sixty or more cars, I fixated on Gordy’s favorite, a red Super Mustang, my interest telling, too eager, too direct, although Gordy seemed not to notice. At some point he took his leave of me for some new activity. Impulsively, I nabbed the coveted vehicle and placed it inside my portable carrying case, only for him to confront me several hours later. An argument ensued. Our mothers intervened.

Gordy explained how the car was his, provided the facts about its purchase.

“It’s my car,” I said.

His eyes held mine in a level gaze, sizing me up, sizing each other up with malice, forgetting everything save our anger and the battle between us.

“Well,” my mother said, “Jeffery has so many cars, too many, dozens of them. He probably just made a mistake.”

I looked at my mother, saw embarrassment expand on her face, read in her features things I had never seen until that moment, a woebegone expression I found hard to witness. Still, I held my ground, insisted that the car belonged to me.

“Jeffery,” she said, “I think you left your car at home.”

I insisted I had not.

I did not understand her dilemma. She could not defend me before her employer.

“Well, Alice, I’m certain this is the car I bought Gordy,” Mrs. Gluckman said. “Why don’t we let Gordy keep this one, and I’ll give you money to buy Jeffery another car? That will clear up the misunderstanding.”

With that, the bargain was struck. I was forced to take this result. Even now, I can see the gleam of triumph in Gordy’s eyes as he reclaimed his Mustang. I felt hurt and humiliated. As I remember it, my mother shot me the quickest of looks, one that I could not interpret. That day, she made no further mention of the matter, as if nothing untoward had happened. It was perhaps for that reason I remained undeterred as a thief. I required certain things from the world to be happy, to be me. Doing the right thing hovered on the margin of my uncertainties and excuses. Perhaps my mother and I were alike in this respect. From time to time, she took small items from her employers, items that we needed and that she knew they would not miss. No harm was done.

I contrived to linger in the bedrooms of the three children to appraise objects of interest, namely books and comic books. My misfortune, the Gluckman kids only read the funnies—Archie, Jughead, Betty and Veronica, Peanuts, and MAD—which did little for me. Still, the Gluckman home remained rich in possibility. I remained hopeful. My efforts were sure to pay off.

My actions did not stem from ill will, were not directed at them. I realized them as people, liked them well enough. Two years older than me, the middle child, Jolene, was slightly overweight, pudgy, quick to smile, not so fast to frown. There was a lightness in her voice that I found pleasing. She was forever at odds with both Gordy and Jenny, the eldest, seven years my senior, who was even then showing signs of the eating disorder that would cut her life short in her early forties. Her body was against her. Pallid, thin, knobby and angular, bony joints, well-boned face, dark smudges under the eyes, a brittleness to her posture, brittle-looking limbs. No end to my sympathy for her. Take what I may from her siblings, I never had to endure any misgivings about stealing from her since I never did.

The day went by like so many more. My mother deep in her duties, the countless chores that needed seeing to, taking no notice of me, moving from room to room in a planned pattern, no wasted motions, her body deft and economical. Four o’clock came. We would soon be leaving. I heard the sound of an approaching motor and tires moving over gravel in the driveway. Heard a car honk its horn.

Before we stepped out the kitchen door, my mother spoke to me about the cicadas in an effort to prepare me. I took her words in, turned them over, accepted them, and, like so much of the rest of the product of her mind, stored them. (Adults know everything.) I stepped onto the cement walkway, only ten feet or so to the station wagon, but I took in the waves of cicadas, saw the way they tossed the sunshine, and could not venture into that glistening landscape. They mocked me. Coward! Chump! Doofus!

I felt my stomach rise and drop. It came to my mind that they were not of this earth, neither above nor below, but were an alien race, invaders. Although I didn’t believe in God—I even used the term “atheist,” called myself one—I mouthed a little prayer. High overhead something caught my attention. It was a signal to me. Now I felt my feet lifting away from the ground, felt my corporeal self go soaring over the yard, over the house, a floating flying counterpart to the alien race. Something directed me, what I must see, what I must not. From the sky I could view the world below, the cicadas glittering like snow, turning the summer afternoon into winter spectacle. I hastened higher. However, knowing the example of Icarus, I did not fly too close to the sun. I made a slow descent then a soft landing on the gravel driveway.

My mother and I climbed into the station wagon. A feathery murmur swept the car as we were greeted by the other members of The North Shore Car Pool. They might have been versions of my mother, all middle-aged women from Chicago’s Southside, all making a living from what they called “daywork,” serving as maids in Chicago’s northern suburbs. I was offered smiles and admiring glances. Driver Virginia Brown was the ladder-climbing capitalist among the group, her mission in life to buy a new car each year, largely from the transit fees she charged and collected. Short and plump with a pug nose that gave her the stereotypical appearance of a pig, she was the oldest of three sisters who looked nothing alike and who resembled their children even less. The youngest, Martha, my favorite, also operated a car pool, while Mary, the eldest, a non-driver, headed up a family of biblical proportions: fifteen children and seventy-five grand and great grandchildren. If Mary bore a mythical status for her begetting abilities, Virginia withstood a sullied reputation because her oldest daughter Diane was dating a Blackstone Ranger, a big no-no in our universe.

All the women looked up to Vanilla, held her in high esteem, found in her a trusted source of been-there-done-that wisdom—she had a decade or more on them and would live to be a hundred years old—and relied on her ability to administer advice. Short, plump, and light complexioned, her smooth skin was to be envied, a real baby-woman. Small and slight, Vy’s weathered face recorded a map of her hard drinking. She was all angles and dour. Wilma’s gold front tooth lit up her dark skin, which stretched over a Halloween pumpkin-round face. She owned her own car but was nervous about driving. What I remember about Esther is that all the life in her body seemed to be in her eyes and her loud laugh that she displayed liberally for everyone in the car.

The women talked about their days.

“Those are some nasty folk. I really hate workin for them. She just drop her draws anywhere in the house.”

“Not as nasty as these people I work for. Girl, let me tell you what Mrs.— did today.”

“This heifer I work for got both y’all beat.”

Esther lit a cigarette. Blew a question at me. “Is that smoke bothering you, baby?”

I lied: “No.”

“Just let me know.”

“I will.”

They started in on the who shot John, me blotting up whatever gossip they chanced to spill.

“Girl, I had to stop myself from cutting that Negro,” Vy said, serious and matter-of-fact. You could tell she meant every word.

“Cut him if he run. Shoot him if he stand still.”

Deep laughter rumbled through the car.

Vy took a swig from a pint of cloudy liquid. Many times before, I had heard my mother and the women gossip behind her back about how she drank on the job.

The talk got around to their husbands or the men they were dating. Given my presence in the car, they spoke in an odd way, speech full of gaps, colored by metaphor, freighted with innuendo. Though I found the conversation puzzling, I remained attentive, picking up on the clues.

“You don’t mean to say?”

“Hmm huh.”

“Don’t that beat everything. The nerve of some folk.”

Lola said something about how Baby—a woman I didn’t know—was treading on her territory. Then Virginia said she had nothing to worry about because Baby was one of them bull-daggers.

My mother shot me a look to see how I was absorbing this. I pretended to be none the wiser, my gaze focused on some sight outside the car. She lit up a Virginia Slim, blew out a raspy stream of smoke.

“Alice, I think that smoke is bothering him.”

“He’ll be okay,” my mother said. “Just roll down your window,” she said.

And so it went, the women sitting through rush hour traffic talking, listening, smoking, drinking, putting in, arguing.

Once home, observing my mother about our apartment, I could see she was troubled, but when I tried to draw her out, I discovered nothing to solve the mystery of her sadness. I marveled at her hardness, pride. I knew that years of battling (the segregated South, my estranged father, daywork) had taught her to insist so little on her rights. This defined her; this was her measure. She submitted to what she did not like. She felt she must go through with what came. She hoped for the best and would take the worst. Not one to complain about her lot in life, only her tired body dropping into bed at night.

That holiday season, the Gluckmans put up a large tree before the fireplace in the parlor as they did every year, a circumference of wrapped presents at the cloth-wrapped base. They bestowed upon my mother a pricey replica of a Fabergé egg made from china that I still own. Festive, my mother appreciated the gift and presented one of her own. It was not lost on her that the Gluckmans were Jews who celebrated Christmas, a phenomenon perhaps explained by a Jewish psychiatrist having taken a Dane for a wife, a combination she thought rare, if not odd. That season of plenty everything had a religious and intensified meaning, as was to be expected, full of mystical ideas about the brotherhood of man and requirements to brood on, to celebrate the world’s most famous son who had been let to die so cruelly. My mother watched The Greatest Story Ever Told and wept.

Despite my many appeals, my mother refused to take me to see the movie. The Frogs had been too much for her.

The weekend after Christmas, I roamed the halls of the school at the Art Institute of Chicago with some other Saturday students, all of us free of care and anxiety, eager and intense, full of excitement and elation, drawing from each other the strength to be mischievous. Parting doors. Peeping in. One room opened into a dark auditorium where a movie projected on the screen.

We stood close together at the back of the theater and watched. Bits and pieces of the film impinge fractionally on my memory. A scalpel cut into flesh. I could tell by the color of the body that the man prone on a surgical gurney was dead. His glazed features seemed illuminated by some grayish inner glow. An overhead lamp throbbed and pulsed light. I could see a second man’s shoulders lifting and lowering, his hand making small motions over the body. I saw a layer of skin cut away, ugliness overlaid with beauty. A glistening organ was removed and placed on a metal tray. Watching, a feeling of stillness came over me. I carry the memory of a second organ being lifted from the corpse and placed onto the metallic tray. I felt the touch of the blade.

“What are they doing?” one of my classmates asked.

“Cutting up the dead.”

“It’s The Exorcist.”

It wasn’t, but it might as well have been.

The doctor faced the camera. His look seemed to travel down to me. I felt the air being pushed from my lungs. My companions started to backpedal away from the images. When I could govern myself again, I, too, turned and left the theater.

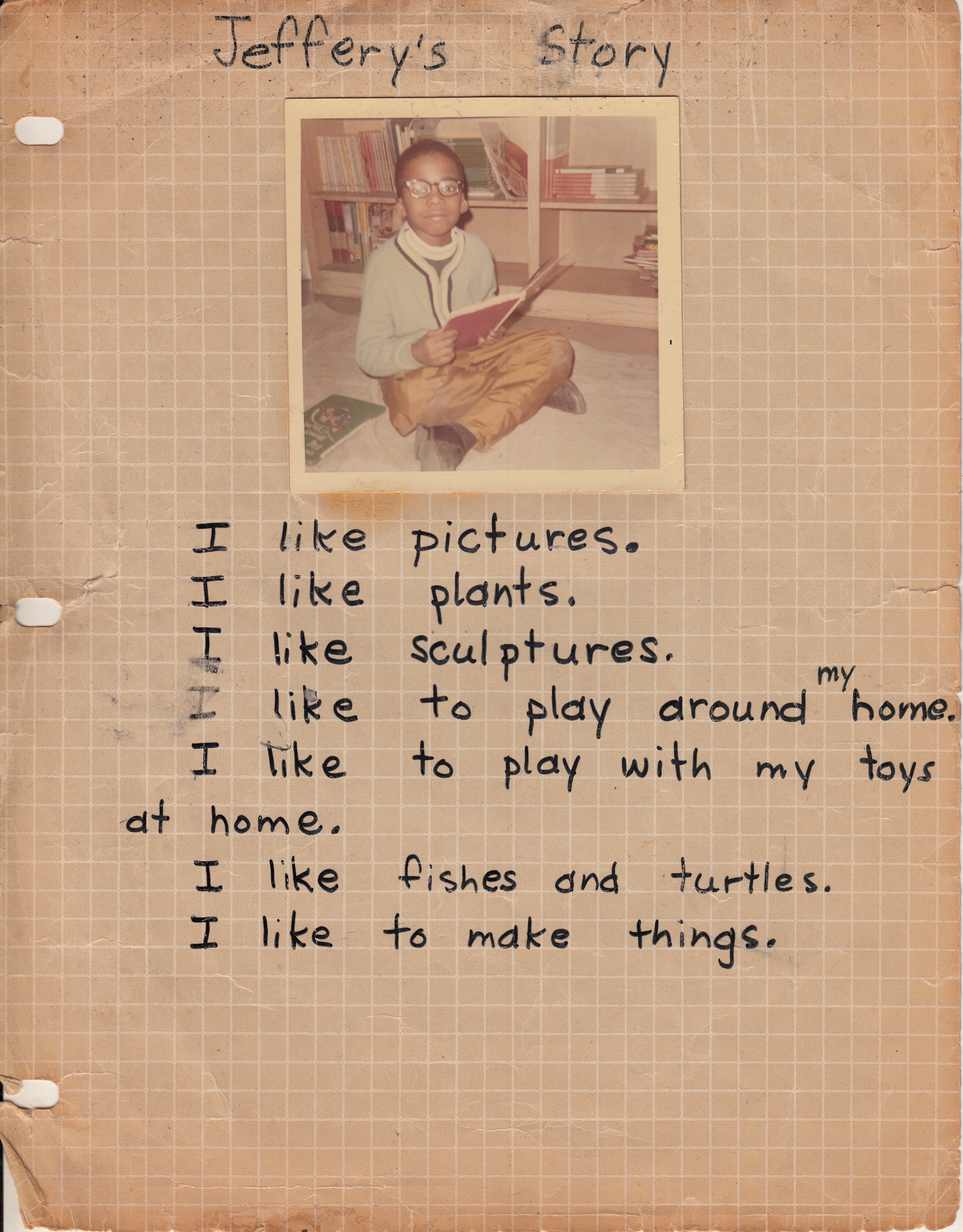

I had been taking Saturday classes at the Art Institute for more than four years. My second-grade teacher at Andrew Carnegie Elementary School in Woodlawn arranged a scholarship for me, although to this day, I remain unsure about why I had been singled out for her notice. I was not particularly good at drawing. In my years to come in elementary school, in high school, I would have one classmate after the next who was better than I was, natural talents. So what had I said or done? What was there in my makeup that she noticed? I suppose I might have had a certain way of putting things even at six or seven years of age. What holds true, I was fated to come into contact with her. She stood with me and for me.

When I received news about the scholarship, I told my mother that I was going to be rich like Picasso. I went about our apartment thinking how perfectly it suited me, this title of artist. I felt strong in myself. Something had been fulfilled in me. Picasso: I felt akin to him. I would be like him.

“We’re going to be rich,” I repeated.

The conviction in my voice produced a long silence in my mother.

We would have our pot of gold. Would have it all just as I had always dreamed of. It was my destiny, our destiny, no more daywork. I was derived from her, I was of her, and my works would also be hers.

To celebrate my acceptance into the program, my mother gave me an art book enlivened by a famous René Magritte painting on the cover, the fiercely bold La durée poignardée, known in English as Time Transfixed. In time, I would see the painting hanging on a wall in a gallery at the Art Institute, would go to view it again and again. Studying the canvas, I could hear the musical motion of the locomotive, the train running by degrees out of the fireplace, panting, gaining speed, the sharp blasts of the chuffing engine striking through me, resounding through me.

Thinking back, I was often not a happy child. Each day brought long moments of melancholia it took hours to recover from. For one thing, I often felt out of sorts when playing with other kids, fearful of evidencing symptoms of asthma. And I was shy, self-conscious about my buck teeth. (Bucky Beaver!) So easy for me to keep to myself. This world, what had it all to do with me? (Did my mother ever wonder when I would come out of my shell?) However, once past the doors of the museum, the tension of daily life was broken. There seemed a magic circle drawn about the place, shutting out the present, the world outside, enclosing another delightful universe, limitless.

I enjoyed watching mobiles churning in the air. In another gallery, a wall-sized painting would come drifting into the light, the most famous work in the museum, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jette, a crowd congregating in knots of conversation before the canvas as I would see many years later with the Mona Lisa at the Louvre. Arrested in wonder and attraction, I would stand alone for a moment, trying to examine the sensation I felt, a fugitive feeling I could scarcely define. Could others in the museum sense the vibration, this strange motion in the air, the way the canvas made the air shake? I stood covered with wonder and interest, suspended. With my mind, I was unable to attend to all the dots that made up the canvas, all the brilliant colors, only the total accumulation. I saw each point hovering in clean-cut isolation, a complete figure, recognized its various characteristics, a finished creation, a tiny radiant thing, a mark of exaltation. A particle of ocean. I seemed to gravitate physically toward the picture, drift. A fine cool subtle touch all over me, saturated. I trusted completely the current that held me, the faint wash of motion in the full space of water.

The museum, a place outside of time, transfixed in time. A place of bygone perfection: how lovely, how formed, how sure all the great works of the past were.

I kept an eye out as I went along the halls and corridors of the school, my attention continually diverted by the various activities I would see in one studio or another: students carving stone, students seated at pottery wheels, young nimble fingers placing pieces of tile into a mosaic or paper into a collage, up-and-coming artists seated before easels sketching a nude woman. With each Saturday, I got more and more into accord with the atmosphere of the place.

Drawing something to myself from the school and the people. Over everything there were great discussions. I would listen and ponder along my own line of thought, feeling of high importance. The same secret seemed to be working inside the others, the same flicker of excitement dancing on all our faces, the same afternoon light falling on us from a studio window, a beam of understanding between us. I was photographed for a pamphlet about the program. I had a showing in Hyde Park, even sold a few of my paintings. A different quality crept into me, or had it always been there?

Once I was in high school, opening out from childhood into manhood, I remained quiet and not noticeable. Too hard for me to catch into connection with the living world. Shy, asthmatic, melancholic, self-conscious, a self-described nonconformist, feeling a want within myself, the whole frame of real life was broken for me, and I discovered an under-space in me that did not care for people. Different from others, art was the only distinction to which I sought to aspire.

While my Saturdays were taken up with the Art Institute, my mother put in work on Chicago’s posh Gold Coast for a widow named Mrs. Abelson, who lived in a two-bedroom condominium on an upper story of a high-rise building overlooking Lake Michigan. You entered a lobby translucent with marble walls and floors and festooned with fresh flowers, a uniformed doorman quick to greet you, attend to you. Boasting all the modern conveniences, circular buttons on the elevator registered the heat from your fingertip. The domicile was an impressive corner unit, the living room wedged with two walls of floor to ceiling windows framing the vast boundless waters of the lake, lake longing to be ocean. (What was the difference? I wondered.)

For the view alone, I welcomed those rare opportunities to visit the condo and stand before glass watching the sun illuminating the blue surface of the water. Flocks of dark waves. Bright boats lifting and drifting in silence. And the ghostly “Hawk” (wind) rising off the lake.

Miss Abelson was to be commended for her good taste. Aesthete that I was, I had every right to occupy space in her universe and brood with joy over the furniture, vases, statuettes, paintings, posters, and prints, and other objects of beauty that she’d taken pains to assemble and arrange. Also to be admired was her rarefied choice in people. Namely, she counted Bette Davis among her close friends. Whenever she had the calling, Davis would escape Hollywood for Miss Abelson’s for a couple of weeks, never leaving the condo. According to my mother, Davis would plant herself on the living room sofa and drink vodka around the clock. Starstruck, this fact did nothing to lower Davis in my estimation.

There came the day when I received a phone call from my mother. “Bette Davis is here,” she said. “Would you like to talk to her?”

“Sure.”

I heard my mother pull the phone away from her mouth and ask, “Will you speak to my son?” Then she was on the phone at the other end, Bette Davis.

She greeted me, using my name. I greeted her in return, an informal hello.

“How are you today?”

“Just fine.”

“Your mother tells me you want to be an artist.”

“Yes.”

I heard her pause, wait for me to say more, but I was not a conversationalist, didn’t know what to say to anyone, let alone a movie star. The best I could come up with: “I like your movies.” Which was true to the extent that I’d seen Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, a film that was released a few months after I was born, easily a dozen times on television, among a handful of flicks—Trilogy of Terror, The Bad Seed (“Give me back my shoes!”), Children of the Damned, Attack of the Giant Leeches, Them!, The Birds—that I never tired of watching. Only later would I become familiar with Bette Davis’s body of work.

She thanked me. Again she waited. I only listened in amazement and bewilderment.

“Well, let me give you back to your mother.”

I was fourteen years old.

The following year, Bette Davis presented a book to me through my mother. It seems that my mother let drop that I was an avid reader, and Davis in turn gave my mother a paperback copy of Thomas Tryon’s novel Harvest Home to pass on to me. My mother didn’t think to have her inscribe it. As I would later discover, Davis had signed on to do the TV miniseries version of the novel. That day, Davis also gave my mother a black-and-white headshot of actor Dorian Harewood. It seems she was advocating in an effort to advance his career, a noble calling. He would later be featured in one of my favorite films, Full Metal Jacket.

I tried to read the book, but for whatever reason, couldn’t get into it. Rather than give up on Tryon, I decided to read his first novel, The Other, and promptly stole a copy from Kroch’s and Brentano’s, Chicago’s largest bookstore. My efforts were rewarded. Pleased to be drawn into a trippy kind of ghost story about Niles, a New England kid in the 1930s, who carries his twin brother’s desiccated finger around in a Prince Albert tobacco tin. Although I had at my disposal only a limited education from Chicago public schools, I was an astute enough reader to recognize that one of the key settings in the narrative, an apple cellar, serves as a stand in for Niles’s mind:

“Shut away from the light, free from intrusion, you felt it was such a place as could be peopled by a boy’s imagination with all the creatures of fancy, with kings, courtiers, and criminals—whatever; stage, temple, prison, down there seeds were sown, to grow magically overnight, like mushrooms. A place whose walls could be made to recede into airy spaciousness, the ceiling and floor into a limitless void, wood and stone and mortar dissolved at will.”

By that time, I possessed a sizeable library, all the volumes either given to me or stolen. The foundation of my collection consisted of a handful of titles I’d commandeered from my mother: a hardback of Sterling Brown’s anthology The Negro Caravan that a boyfriend had given her many years ago back in high school in Memphis, along with paperback copies of Richard Wright’s Eight Men, Thomas Hardy’s Return of the Native, George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion, George Eliot’s Silas Marner, Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, and Bel Kaufman’s Up the Down Staircase. Commandeered but never read since I gravitated toward science fiction, mysteries, and horror.I recall only one occasion where I asked my mother for money to buy a book, Jack Dempsey’s autobiography. Not only did she refuse, she became angry, she became belligerent, she started crying, a reaction that startled me.

“Can’t you see what they have done to us?” she said.

What did she mean? I wasn’t aware that Jack Dempsey had done anything to “us.”

Eventually, she had a change of heart and gave me the money. I needed her; we needed each other. I was dependent on her. Without her, I felt some unidentifiable part of me would be lost. Still, never again would I ask her for money for a book.

She did not raise me to become a thief. Perhaps I thought I was redressing the balance. My motives remain unclear. What is certain, I had come into my own as a thief. I had been at it for many months, a year, two years. Knowing no bounds, without safe limits, I had acquired a few hundred books, including every Agatha Christie and Ellery Queen, Ray Bradbury and Harlan Ellison, all the anthologies edited by Alfred Hitchcock, novels that were based on movies or that had been turned into movies (The Towering Inferno, Jaws, and The Taking of Pelham One Two Three), and a choice selection of philosophy, religion, and biographies of figures I admired (Muhammad Ali, Harry Houdini, Bruce Lee, Hank Aaron).

One day like any other, I went inside Kroch’s and Brentano’s and assumed my rights to take anything I wanted. Through several long minutes I filled up a shopping bag then headed for the exit, confident I was unseen. A man darted past me to the doors, forestalling me. A square-looking white dude of average height and build underneath a Chester the Molester trench coat stood in my path. He drew me in with a look.

“Please open your bag,” he said.

I opened the bag. He looked inside then took it from me.

“Come with me,” he said.

A great astonishment burst upon me, the air broken. A weakness ran over my body, a relaxing, loss of strength. He repeated his command, but I could not move. It was if a sediment had settled in my mind and flesh. He placed his hand along my shoulder, a bit of pressure, a modicum of force. I had one opportunity to break for the door, that or dispatch him with a few well-placed punches and kicks I’d gleaned from several purloined martial arts manuals. Instead, I about-faced then vaguely wandered forward, drifting, his hand still on my shoulder, a current guiding me, directing me. To where?

He ushered me into a tiny office and pointed to a chair next to a desk where I should sit, seating himself behind the desk with a glistening look of seriousness on his face. Now my whole being opened itself up to the awful realization that flooded in on me: I had been caught. I felt an oppression on my breathing. In the terrible tension in the room, I took in his perfectly trimmed hair in contrast to his bushy eyebrows and hairy knuckles.

He took up a clipboard outfitted with pen and a blank form and began speaking to me in a no-nonsense tone. Name? Age? Address? Phone number? There lay between us these two things: his questions, my answers. He had ceased to be a man, only a moving mouth like Clutch Cargo. For whatever reason, I answered his questions truthfully. I could feel our voices, his and mine, ringing in the motionless air of the little office. He wrote down my answers on the form, filling in the blanks.

“Who do you live with?”

“My mother.”

“I’m going to call her now.”

He picked up the receiver and punched the numbers into the dial-box.

“My mother is at work,” I said.

He ignored me and continued to listen on the line. After some time he put the receiver down and looked at me. I was thankful we didn’t own an answering machine.

“She’s at work,” I said.

“What’s the number there?”

“I don’t know it.”

“Are you sure?” He watched me steadily. Looked on with mistrust and wonder.

“I can never remember it.” I felt fear moving around inside me, shifting and growing.

“Where does she work?”

“In Winnetka.”

“Where? Doing what?”

I started to say “daywork.” Instead I said, “In a private home.”

“And you don’t know the number there?”

“No.”

A frown tightened his face. He did not speak for some moments, distances of silence between us.

I didn’t want to cry, but tears were not to be avoided.

He looked at the phone, then he tried my home number again. Disappointed. He asked me why I had taken the books. I was slow in answering.

“What would your mother say?”

“She would be disappointed.”

I saw his pointed interest in my response. The store dick made a visible effort to soften the sternness of his features. I waited for what he would say next.

He took to his feet. “Stay here,” he said and quit the room.

I sat still and let the minutes go by, the room full of the sense of waiting.

After some time, he came back in, retook his seat, picked up another form on the desk, and, reaching from his seated posture in the chair, he placed the form before me. “Read it,” he said.

I read it.

“Do you understand what it says?”

“Yes.”

“I want you to say the words out loud so that I know you understand.”

“I will never come back to the store.”

Now sign the form.

I signed the statement. He informed me that I was free to go. I surged up out of the chair as if a great weight had been lifted from me.

A few weeks later, I was caught trying to steal a magazine from a black-owned record and incense shop in the neighborhood where I lived. Thinking myself unobserved, I left the store with the magazine hidden at my side. I hadn’t gone ten feet when I felt someone come up next to me and hook his arm into my arm, his body imprisoning mine. I struggled, twisted, tried to pull away, free myself, but I did not have enough fight in me to match him, no strength of mine equal to his. He seemed to balance me perfectly in opposition to himself, lifting me nearer and nearer to him in our dual motion of walking, our feet making companionable sounds on the sidewalk.

I dropped the magazine.

Without letting me go, he stopped, stooped down and picked it up with his free hand. Then he was again yanking and pulling and dragging me back toward the store with all the weight and strength of a full-grown mature body.

Once back inside, he pushed me roughly against a wall and stood a few feet away, a short, stocky, stoutly-built, bullish type outfitted in a three-piece suit and tie and platform shoes, at once fashionable and individual. Perhaps my mother’s age or a few years younger. His head shaved bald. His face adorned with a vigorous goatee.

He raised his fist in a swift denunciating gesture. “Do you know how hard I work?” he said, his mouth pulled down in an angry curve.

This was received in silence, a weight in the air. I stood with my shoulders tight, my stomach unsettled, and felt everything go quiet inside me.

“And you want to steal from me. You come to take the hat off my head,” he said. He was returning my look, waiting.

I felt the flush of embarrassment. I had no defenses. What excuse could I make? I apologized although I was scarcely able to speak. And I apologized again and again. I had an impulse to kneel and plead forgiveness. Something inside me would not allow it.

He stared at me heavily for some time, forced his voice and his body into control. I’m not going to call the police.

Instead, he put me to work for two or three hours in the store, placing stock on the shelves, taking out the garbage, sweeping, mopping, and other odds and ends. I was happy to perform the duties he gave me, forgetting my troubles, moving in another concentrated world, until everything was clean, organized, and still. Lesson learned, he made a little gesture of dismissal with his hand. I was free to go home. Part of me was reluctant to leave, for I longed to smooth away any lingering doubts he had about me. After all, I might see him again in the neighborhood. What could I say to him to get on to a new, more ordinary footing, to let him know that I was not a bad person? Rather than give him the wrong impression, I put the thought away and left the shop. Perhaps an unspoken understanding was exchanged. I made a silent promise to myself: I would never steal again.

A few weeks later, I accompanied my mother to the Gluckman’s house. The day came blue and full of sunshine. Blotches of brilliant color around the house. Pure clean light. Wind moving my clothes. I had it in mind to draw the house and had come prepared with my sketchbook and oil pastels. The lawn sloped golden in the morning clarity. Big and splendid, the trees balanced perfect on either side of the house, a brown-gray scaffolding of trunks and boughs with level sprays of green. The morning had a hush of excitement, birds whistling inside the leaves.

I stood suspended on the grass, soft and fine under my sneakers. It filled me with ease to see the house. The sky above it full of traveling light. A white gleam on the roof that held like a blade in the sky. Changeless radiance. I made a few strokes, deliberate delicate carefulness of movement. I drew slowly, concentrating. Soon, the fragments caught together, a resemblance, the house coming into being on the paper. My fingers had the structure under their power. Time passed unheeded and unknown. Alone in a little wild world of my own, complete doing this thing I enjoyed, strong and unquestioned. Surely, I must have taken a break to eat the lunch my mother prepared.

I tried sketch after sketch that day, hitting closer to the mark with each draft. Seemed to catch the roof, the angles of the gable, the way the tiles tucked into one another, but then the house would draw away, reluctant to yield to my paper and colors. As the day wore on, I made no progress, mere mechanical activity, rotary motion. The very air all around me started to feel intangible. Try as I might, the house proved to be beyond my ability to capture it.

Back home in bed that night, I lay in the dark, my body following the usual preparation for sleep: tilted on my left side with my right leg drawn up. Eventually, left leg drawn up, head to right, weight slowly given to the right side. Listening to sounds that came from all directions. As always, the lonely feeling came over me, a longing for something—what, I did not know—my mind filling up with thoughts and questions, puzzling over the misery of existence and the peculiar fact that I was alive. Then something new happened.

I recognized that the darkness had dimensions, so high and so wide and so much across. It seemed to sway in waves, blackness leaping and plunging. With each movement the darkness began to dilute, lessen, lighten, take on brightness, eventually glow out into a clear space that filled with an image of the Gluckman’s yard where I had stood drawing on the grass. The yard spread so wide and far and deep that it seemed unending, stretching away from the driveway in gentle undulations as far as my eye could see. My sight traveled on to the front door of the house and past the threshold inside and into the parlor. A scene began to form. People seated at various points in the room, including a man before the piano, not the Gluckmans but black people like me and my mother. A husband/father, a wife/mother, and two or three offspring. I gave them features, characteristics. Now what? I heard them express words. An argument? No, a discussion, playful, light banter. They began to move about, interact. I saw the passion they had for each other, charged feelings.

Then a new scene began to play out, this time in the basement, between husband and wife. He stood balanced opposite her for some moments, considering what to say to her. There was for him the most intense pleasure in talking about anything to her. I heard a door close. One of the children had scuttled out of the house, a matter that needed attending to. This was life for them. The scene played on until I fell sleep.

The next night the cicadas had once again taken over the property, but to be alone in that insect world was to be at peace. The family did not feel in the least disturbed by them. The man pulled his pack of squares (Cools) from his shirt pocket, struck a match, and inhaled for some time before blowing two streams of smoke from his nostrils. His wife decided to join him, so he obliged her, tapped out one from the pack, placed it in her mouth, and bent forward to light his to hers. She had small beautiful hands.

Another scene began to unfold, this time involving one of the children, yes, the oldest daughter. Her long comic face, her sad eyes. The way she spoke. The thoughts turning over in her mind. Why might she not borrow her father’s car? Why might she not pay her boyfriend a visit? Her breath came short at the idea.

Each night, new scenes, new stories. My own soap opera. Always this family, always the Gluckman’s house, a house that no longer belonged to them, a house taken over by people from my imagination. One morning, it occurred to me that I should preserve these dramas, write them down, fashion them on paper. So I did. And everything changed.