The first subject matter for painting was animal. Probably the first paint was animal blood.

—John Berger, Why Look at Animals?

WITHERS

On Valentine’s Day, Milo strings a horse-shaped piñata from the ceiling light in our living room, and I walk by twice before noticing it sways there. The light is off and the horse is dark, but I am not unobservant. Part of me accepts a horse swinging in my periphery. Milo makes up a real reason for me to go back down the hall and, when I look for the space heater, I find the horse hanging. He dangles from a yellow jump rope, and I am so happy to see him in my house. Milo hands me the stick. “You need,” he says, “to kill a horse.”

This horse is not strawberry scented or shedding glitter. He’s the brownest brown I’ve always reached for. “God’s favorite color,” I heard an auctioneer say last week about three brown horses in a row. “Must be why he made so many of them.” Somewhere there is a piñata factory. Take me there to see the assembly line of hollow wonders, the conveyor belt of cardboard joys built to be stuffed and smashed. I want to shake the hand of whoever made this horse look so Horse that I approach it as I’ve learned to, with my open palm slow and flat. The piñata has a black mane of thinnest paper fighting to fall right. I know it isn’t breathing. The long tail flicks. His muzzle curves soft, his ears point like they should, and this is what matters most. I don’t quite believe this empty horse has no spine.

The stick is small. “No spinning, no blindfold,” says Milo. We both know I need to see what I’m doing, not to be cruel, but because the gift is the taboo, and candy on the floor the only consequence. No animals will be harmed in the making of this thought experiment. I bring my elbows up to hold the stick over my shoulder, and the horse sways in anticipation. He cannot run. I hit him on the back, and he doesn’t break, not even a dent. I’m not hitting this horse like I believe there’s a prize inside. He swings away from me, then comes back again. I’ve said if I can kill the horse, I’ll finally know it, but I lose the point I’m trying to make as soon as I go from thinking to holding a weapon. I can’t take this paper game seriously. I take it way too seriously. This is a love story.

I narrow the distance between each strike, landing quick at the horse’s hip, then his neck, and now the light is wobbling. I turn the stick into a spear and stab the horse’s side. His perforated stomach bends into itself until treats tumble out: tamarind candy, peppermint tea, chocolate-dipped cherries, and a wrapped wedge of cheese. Tonight for dinner, Milo and I will eat the horse’s insides, so I sweep the candy in one pile and pieces of tail into another. I fold the horse’s four legs in half for recycling. I pick up the rest of his creased and broken body and pet his nose. I never hit the head; I rip it from his shoulders, finger comb his mane back to the right side, and sit the horse, bodiless, on my reading chair. “We’re keeping him,” I say, then slice some bread and peel open a tin of sardines. Their heads are cut off too, their bodies packed in oil. Milo and I put the meat on the bread with our dripping fingers. I cannot feel the spines when I eat one and then another.

PASTERN

A poem I love by Larry Levis begins, “Perhaps the ankle of a horse is holy.” Horses don’t have ankles, but they do have elbows and forearms and knees. They also have cannons and hocks, gaskins and coronets. The horse is a whole chorus of bones stacked and slim. Horse hooves absorb twice the animal’s weight at a gallop. Underneath more than one thousand pounds, the hoof’s keratin walls expand on impact. Each step sends blood back up the leg, and the horse’s body recirculates itself in motion. When people say the horse has five hearts, they mean one organ and four feet. “If the ankle of a horse is holy,” wonders Levis,

& if it fails

In the stretch & the horse goes down, &

The jockey in the bright shouts of his silks

Is pitched headlong onto

The track, & maimed, & if later, the horse is

Destroyed, & all that is holy

The jockey in the bright shouts of his silks

Is pitched headlong onto

The track, & maimed, & if later, the horse is

Destroyed, & all that is holy

Is also destroyed, hundreds of bones & muscles that

Tried their best to be pure flight, a lyric

Made flesh, then

I would like to go home, please.

Tried their best to be pure flight, a lyric

Made flesh, then

I would like to go home, please.

Levis is the one poet I’ve read who can kill a horse—or come close to trying. Even here, with the maiming, Levis only snaps a conditional ankle, and he can hardly stand the hypothetical. Horse, rider, writer, and reader are temporarily safe in the if of it all. I’m still relieved by the shadow of this mortal, fallible horse because I can’t find its shape anywhere else. All the horses in all the horse poems are so good. Even in death, if they’re allowed death, they are beautiful and blazing, ready to rot with majesty. These are half horses, all essence, no bones.

The horse is a beast of actual and abstract burden. It offers an extension of the human body—height, strength, and speed—and lends itself to the weight of our fantasies on and off the page with unique duality. Saddle a horse with a typically opposed pair, and the animal carries them each with ease. The equine body represents both strength and softness, masculine and feminine, domestication and wildness; whatever is repressed or inaccessible in the person can become fully realized as a disparate aspect of the animal. When I’m with a horse, and when I write one, I assign it autonomy in one breath and resignation in another. I prefer the symbol for the body it allows me to express and reject.

HOCK

Just north of the imported green of each golf course in Reno, I pull to the side of the highway and watch a roaming band ignore me as they sniff the dry ground for grass. These are not racehorses, but wild ones. Wild is the legal name for horses born or abandoned on federal, public land. These horses are down from the hills again looking for food. Horses graze in selective circles, returning to the same ground to keep mowing it. This little group nibbles sparse and browned brush and does not look up at the sound of trucks grinding past them. They are unbothered by wheels and planes and me. They are the kind of wild that recognizes all the shapes of a tamed world, the kind of wild that people wake up to find on their front lawns, but I’ve never seen them painted this way on football jerseys and classic cars. As a logo, the mustang is always running, forever rearing around the sunset, freedom branded as unrestricted motion, the liberty to pump their own blood with every stride, and for me to do the same. I resent these mascots for what they don’t say, and I invoke them, leaning hardest on the horse when I want it to speak for me. The symbol says themes I’m afraid to spell out because they’re huge and hackneyed and I want them: Independence and Redemption, the shadow I call Country, and my faithful complicities. The paper horse sags with the weight of my ideals and anxieties. What a relief to be carried down the page by something else.

The band is across the street from the Wild Horse and Burro Center at Palomino Valley. The horses are grazing, untouched, in plain sight of dirt paddocks filled with one thousand rounded-up others. Palomino Valley is open to visitors nine to five, five days a week, except on national holidays. They keep the American flag raised high and the porta-potties spotless in the manner of a place used to scrutiny. Since the Wild and Free Roaming Horse and Burro Act of 1971 placed those animals under the immediate jurisdiction of the Bureau of Land Management, that management has been criticized. The BLM is responsible for the “health, diversity, and productivity of public lands,” which includes the competing agendas of that public: recreation, conservation, production, and extraction. Their data reflects the discordance. The horse population is disputed and a distraction within a larger debate about the fate of public land. By the time you read this, the numbers will have already changed, but I want a record of the dissonance, the difference between what’s on the ground and what’s in our heads. Population estimates gathered by the BLM as of March 2024 report at least 73,000 horses and burros roaming Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, and Wyoming. This does not include the additional hundreds, possibly thousands, on state-run and tribal land. While the government estimates these Western states can healthily support 26,000 horses total, more than 28,000 live in Nevada alone.

Nevada is the battle-born Great Basin. No water that falls or flows there ever reaches the sea, every drop absorbed or evaporated in the dry and dramatic libertarian stronghold where lake beds crack into death valleys. Aridity breeds both defiance and fragility. Nevada is the driest state in the Union and getting drier. A healthy horse drinks at least five gallons of water a day. Most mares foal once a year; the herds double in size every four. This growth rate is more characteristic of an invasive species than a native one. The mustang is the icon of a landscape that cannot sustain it and will not recover while trying. In the United States, the only animal with more federal protection is the bald eagle.

An emblem earns unique status. Free-roaming horses are categorized like no other species; they’re not game, they’re not livestock, not endangered, not considered a resource. Wild is not the kind of word that will respond to a claim like feral. Slaughtering wild horses is illegal and so is exporting them. Fewer than five percent are adopted domestically each year. The government remains legally obligated to remove them from the land and does so with the aid of helicopters. Most of the 73,000 horses already taken off the range will spend the rest of their lives standing separated by age and sex in long-term holding. The vast majority of the BLM’s wild horse and burro budget goes to feeding these animals, leaving little money leftover for alternative management strategies, like fertility control or habitat conservation. The projected cost for this year is more than $154 million taxpayer dollars. By the time all the removed horses are fed from now until they die, the bill will reach one billion. Meanwhile, ecosystems crumble, less symbolic animals suffer, and wild horses walk toward the interstate looking for the food people leave them. Tell me it’s not in all our natures to save something to death.

STIFLE

Peter Shaffer’s 1973 play Equus starts with six horses stabbed offstage. The character Alan is young and confused, possibly ill. He has to be sick, having claimed, as he does, to see God in the horse. Alan creates an amalgam of all that is holy in the body of the animal, and he trembles before his most exalted, Equus. Then he blinds his beloved with a shit-scraping hoof pick rather than let the divine watch him in sin. Only crazy and cruel people kill horses, and the play is powered by those consequences. Alan is tried, detained, and ordered psychiatric treatment. Convention says the boy will be healed and the public safe if he’s cured of his violence. He’ll be at peace, finally, once he’s no longer ruled by the compulsions of his distorted passion. The court-assigned psychologist is more curious than judgmental. In tracing the origins of Alan’s obsession, Dr. Dysart begins to doubt his own therapeutic aims. He wants the boy safe, he wants animals unharmed, and he fears the cost of that peace. “Can you think,” asks Dr. Dysart, “of anything worse one can do to anybody than take away their worship?”

Sometimes I’m disconcerted with how quick I am to imagine violence as the solution to the wild horse numbers. I’m not worried I’m callous; I’m disappointed in my lack of imagination, naming a problem only to suggest disappearing it. I know I cannot split the body of the horse from its meaning, but I keep pulling them apart. I keep trying to kill one in order to hold the other, as if the symbol must die for the flesh to be real, as if real can be severed from its own representation. I’m jabbing at the symbol, poking a hole in its side hoping the power will leak out when the body goes limp, but it doesn’t. No fact is sharp enough.

BARREL

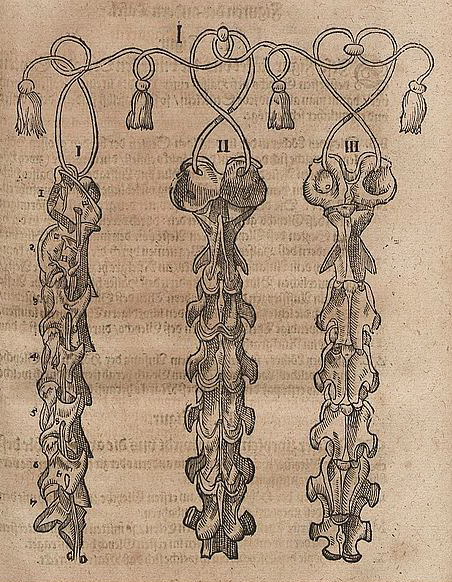

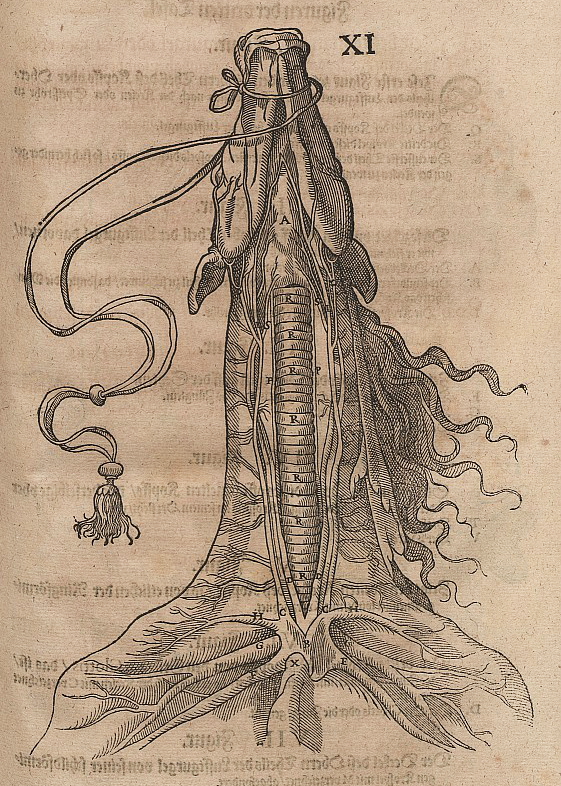

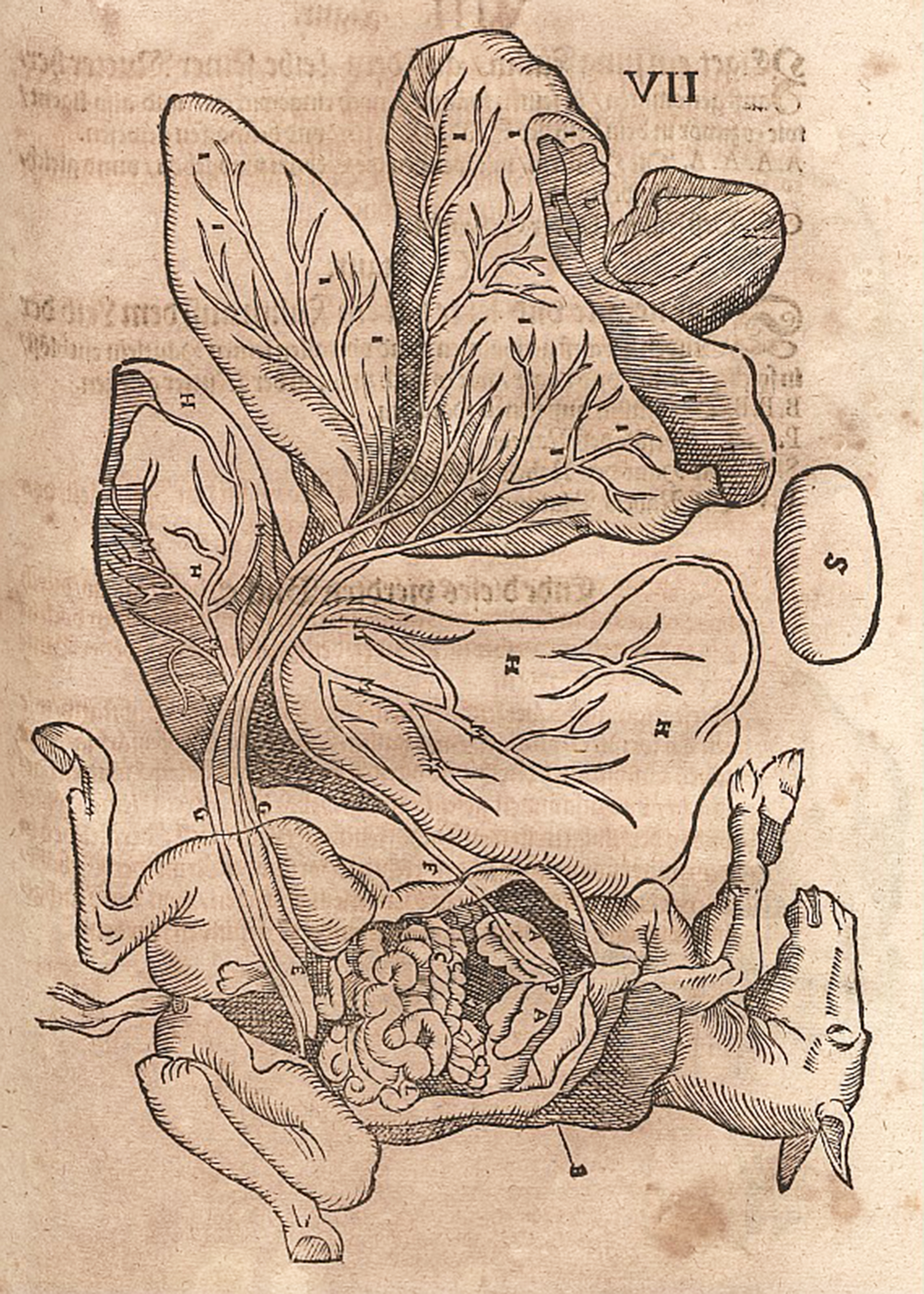

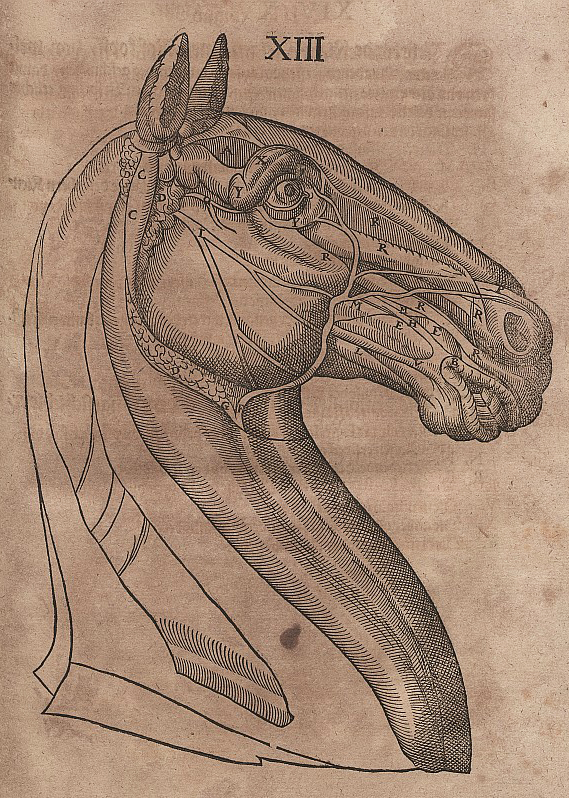

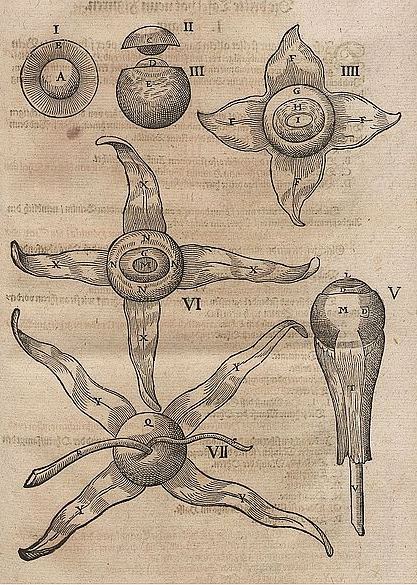

The first formulation of blood as something that flows inside us came from a sixteenth-century Spanish ferrier’s manual. In 1547, while describing how best to nail a shoe to the hoof, Francisco de la Reyna wrote, “la sangre anda en torno y ruedo por todo los miembros y venas.” The blood travels around and rolls through all the limbs and veins. By the sixteenth century, so much of the Western world depended on the health of horses that veterinary and human medicine developed as almost parallel sciences. In 1598, Italian anatomist Carlo Ruini wrote the first monograph of a species besides man. Dell’anatomia et dell’infirmita del cavallo is seven hundred fifty-nine pages of equine anatomy detailing a body I think I recognize in a language I cannot read. The pictures are so fine that da Vinci is rumored to have drawn them. Masterpieces, a piece of some master, dozens of crosshatched cross sections of the horse split into lines so thin there are shadows in the crease of each muscle. I turn the page. I crawl in.

I find the spine shown from three angles. Each column is a tessellation of bones strung like flowers to dry. They are linked by a tasseled rope that must have, by the pride of it, been golden thread. The flesh is splendid, each diagram adorned. In another drawing, the same tassels threaded through the spine are now wrapped around the mouth of the horse whose throat is splayed to show its esophagus. The horse has been split by a scalpel down the middle, but his hair still blows in the wind. Ribbons of mane are curled just like the rope, both reins and tendrils drawn in ringlets. Veins and tendons frame the organs in symmetrical branches. I have no other word for them but ardent. In table I of book III, two human hands have been drawn pulling back the skin to reveal the heart. The cut spans the entire length of the horse’s stomach. No bones. The heart is twice the size of the hands revealing it. The horse’s eyes are drawn blank.

The prints are woodcuts, each line is a knife, and there’s no stench to these pictures the way there must have been in making them. The hands pulling back the skin are clean. In this flattened way, I can say there’s reverence in opening something up. From the gallery of the operating theater of my mind, I can call dissection an irrevocable intimacy. The knowledge comes from never being able to put the body back together.

I print the diagrams and spread muscles and tendons around me. I tape the ribs to our kitchen walls, sit down inside the cavity, and build back the round cage from within. The light comes through the hole I’ve cut, and I lie down, my spine over the animal’s. The air is dripping. To my right a noisy small intestine is busy with digestion. The organ itself is seventy feet long, which is exactly the kind of marvel slicing something open yields and not what I was looking for. I came in for a word, number, or nucleus, some churning engine or absence. I’d be lying if I said I wouldn’t carry that piece of the animal out with me if I could. I’ve pocketed rocks off a beach I was supposed to leave the way I found it. But now I want empty hands. I want what I’ll never find dissecting, and I want never to find it, to get closer like this. I crawl out.

Table II of book I shows the horse’s eyes six ways. From above, from below, from the side, and peeled open three more times to bloom. Milo comes home to me in the middle of a flowering cornea with four petals. Like the California poppy, whose orange faces unfurl down our street, these ancient eyeballs unfold on our counter. I offer him the retina like I’ve picked it. Milo takes my bouquet and fills a tall jar with water. He sets it all on our kitchen table and we eat dinner while the eyes roll left and right. Horses have the biggest eyes of any mammal on land, evolved to scan for threats they no longer know are extinct. I’ve studied the horse so much I don’t see it anymore, or I see it everywhere and can no longer tell the difference.

DOCK

The horse evolved in North America with the other massive mammals of the Pleistocene: the wooly mammoth and the saber-toothed tiger, the giant sloth and an enormous armadillo. The same mass extinction that turned those animals into fossils wiped out all the prehistoric equine species who had not already migrated across the land bridge to Eurasia, where the horse was domesticated by the nomads of what is now northern Kazakhstan. That partnership permanently altered the way we ate, moved, and warred. Agriculture changed, language developed, and conquest spread. When, thousands of years later, the Spanish expanded their colonial campaigns to the Americas on horseback, they reintroduced the species to a landscape that had long been without it. The grass was different, the big cats were gone, and the domesticated horses returning to North America were no longer an integral part of the natural system, but they became indispensable to both those claiming the land and the Native people defending it.

Mustang likely comes from the Spanish word mesteño, for stray or ownerless. The etymology, like the origin of the animal itself, remains crowded, contested, and inextricable from legacies of invasion. Another root is cimarrón, a word for wild and untamed that also described peoples living on the outskirts, escaped from slavery in the Caribbean. The horses roaming the United States today are the descendents of a long-tamed mix: the animals abandoned by retreating Spanish forces, the horses escaped or released during battles between settlers and nations, the result of gates left open and the invention of barbed wire, ranch horses mixing with the roaming ones. As the United States parceled and privatized itself across the Great Plains and Texas, the herds were moved into the increasingly dry and vulnerable landscapes of the American West. The 1971 act mandates the Bureau of Land Management “maintain a thriving ecological balance” while also protecting the horses. Balance not just between the horses and the land, but everyone and everything else on it: all the endemic grasses and grouses, the pronghorn and the trout, the streams and rivers still left. Balance, the act commands, between the delicate cycle of the sagebrush steppe and the businesses of extraction, beef and lithium. Balance between the native species and our imported demands.

FLANK

I hear a biologist say the word predation seven times, and it sounds beautiful. “Prey,” she says, like pray. I know she’s describing claws sunk into a horse’s spine and teeth snapping the neck of a foal, but I hear hands pressed palm to palm over a meal, together, tired, and grateful. I put the word in my mouth where it is round and warm. Predation of wild horses is low. There are no more dire wolves or American cheetahs. Of the cats that are left, only mountain lions hunt horses, only some lions, and only some horses. Mountain lions learn prey preference from their mothers. The cubs are trained hunting what their mom wants to eat most. The biologist refers to this subset of lions as “wild horse specialists.” This is also a title I’ve given myself.

I don’t talk much around horses. I don’t talk much to them. It’s not because they don’t talk back but because I could say anything. Instead, once a week at the barn up the road, I lead the lesson horse from her stall and repeat one small song. “Good girl,” I say, brushing dust from her legs. “Good girl,” I say, picking shit from her hooves. I pluck hay from her tail, I cinch the saddle in place. Barely two notes, the words back and forth, “good girl” while she rolls the bit in her mouth and “good girl” while her back tenses beneath me. “Good girl” tells us both to modulate instinct. I say “good girl” to promise her I’m not a threat. “Good girl” convinces me I could be. Even the horses removed from the range can be tamed with a few months of steady hands. They carry the genetic memory of an animal we bred to accept our touch.

An animal is wild when it exists in equilibrium with its environment. When birth and death weigh on each other in something like equal measure. Domestication removes an animal from the process of evolving toward that attempted equipoise with its ecosystem. The horse’s gut is different now that they’ve depended on being fed for thousands of years, and so is mine. Balance is an impossible goal in an invaded landscape. Maybe that’s the prayer of predation, an actually natural order. But that is not a peaceful prayer. If equilibrium is really what I want, I would have to kill for it. I would have to accept being hunted. Today I paid eight dollars for a chocolate rabbit.

CROUP

I’ve never eaten horse meat. Not knowingly, not willingly. I saw it on the menu once north of Reykjavík, and I avoided it then like I do now. I eyed the plates at other peoples’ tables, wondering which steak was horse, not recognizing it if it was, so distracted then that I forget now what other animal I cut into that night. Since humans met the horse, their meat has been both scandal and sacred. A necessity, a norm, a symbol of desperation turned to only in times of extreme poverty, the last resort of a retreating soldier or the cheapest choice for a desperate mother. Kings bathed in horse broth, were buried with their horses, or killed people for such a ritual. The same meat that meant sacrilege to some conferred strength to others. The Bible gives some rules, and so does the Qur’an, but neither say exactly what’s allowed as far as the horse is concerned. Smoked, salted, or sashimi. In a stew, with rice noodles, stuffed in sausage, chopped tartare. Openly sold and consumed in an incomplete list of countries the US might call ally or enemy: France and Japan, China and Russia, Canada, Kazakhstan, Mexico, Italy. There’s no word for the meat in American English because there’s no business that needs one. We might import the French word chevaline if an industry returned, but the lack of language is further proof horsemeat is not anything Americans want to put in their mouths. Instead, horsemeat remains a distinction to draw between what’s civilized and who is foreign. Much like two thousand years ago, when the Romans declared the peoples they invaded pagan for eating the very animal they themselves had ridden to subjugate those civilizations.

I can’t find an American to talk to about horsemeat. Susanna is a British writer, scholar, and stranger now living in Sweden. In the few waking hours overlapping our time zones, she agrees right away to talk about hippophagy; she’s not often asked. Her small daughter should be asleep but sits for our call instead and holds a stuffed horse over her face. Maybe, some arguments go, a horse raised for consumption is more likely to be fed, treated, and slaughtered under conditions of care, its body precious—or at least regulated—merchandise all the way to the end. It’s true I already pay extra for grass-fed, hormone-free, open-range. But what saves and dooms the horse from as manufactured a fate is that the animal is already a commodity. “A serial one,” says Susanna, “protean.” In their twenty, maybe thirty-year lifespan, a horse may go from athlete to laborer to companion. A barrel racer becomes a therapy horse becomes a lawnmower; a ranch horse switches owners three times before retirement; the same pony is the first horse to five different little girls. The difficulty in adding one more distinction, one more use for the horse’s body, is that we consider their labor a loyalty. There must be respect for their flesh. It must not be called flesh. This is the logic of a culture, mine, less averse to actual meat than to the methods of its command and production, but only where the horse is concerned. Horse is iron rich and low in fat. I’ve never eaten it, and I can still tell you it’s hard to swallow.

THROAT LATCH

The stage directions for Equus are precise about how the horses should be realized. No pantomime, no tails:

The actors wear tracksuits of chestnut velvet. On their feet are light strutted hooves, about four inches high, set on metal horseshoes. On their hands are gloves of the same color. On their heads are tough masks made of alternating bands of silver wire and leather; their eyes are outlined by leather blinkers. The actors’ own heads are seen beneath them: no attempt should be made to conceal them.

The play, both its violence and its redemption, depends not on a believable horse, but the person inside it made visible.Cut me open, and my origin story must be at the center, a ligament of my spinal column or somewhere along my small intestine: the place where my insides do their explaining. There you might find the reason that keeps me circling this animal. A source, something like my first memory of a horse is being bitten by one. I was lifted up to the fence of a summer field, I curled my fingers in an open mouth, and I cried as I was carried away because it hurt and because I wanted to go back. I’ve never been able to hold my hand back from the hot lip of a horse, if I can help it. This is the kind of memory that wants to be an answer.

Sometimes I resent being asked “Why horses?” as if the answer is seven. I can’t point to the beginning of my curiosity, which is what sustains it. Every time I try to diagram my origin, I end up with an invented diagnosis: Horse as birthright, best friend, or protector. Horse as mother herself; I could have evolved from hooves of my own, born knock-kneed and running. Ask me where this all started, and my answer is something closer to heat. I’ve tried to break it apart and call each piece a reason. In my hands the rendered animal grows cold.

POLL

At the height of production, the Cavel West plant slaughtered five hundred horses a week and shipped the meat to Europe. Locals complained about the Belgian-owned abattoir, the smell and the sound of it, the blood that would sometimes back up the sewer system and spill out of storm drains. Most of the horses were mustangs, adopted at a low cost from the Bureau of Land Management, then resold for slaughter. On July 21, 1997, Joseph Dibee and four others set fire to the plant by drilling holes in the wall and filling them with a flammable mixture they called vegan Jell-O. Dibee was also connected to arson damage at a BLM holding facility for wild horses in Northern California. He was indicted in 2006, and spent the next thirteen years as a fugitive on the FBI’s Most Wanted list of domestic terrorists until he was arrested in Cuba. Cavel West was never rebuilt, and the last horse-slaughter plant in the United States closed in 2007. ZOOS IN A PICKLE OVER HORSEMEAT, wrote the Seattle Times that year. The paper published a picture of Kwanzaa, a South African lion nosing a lumpy, three-tiered birthday cake made with ten pounds of horsemeat. Whipped cream dripped down the sides, and a carrot candle sat on top. Without a steady supply of horsemeat, many zoos struggled to feed their big cats.

Horses are still slaughtered, but now they are shipped across our borders north and south. No rules and no records, an underground mix of ownerless and once-owned—too old, too injured, too expensive, too many—smuggled across state lines. For beloved horses, the legal options for the inevitable body are more costly and more complicated than for any other animal we call a pet. Imagine a horse-sized hole in the ground. Laws vary state by state how deep the hole must be dug, how far from water sources and public roads. Horses treated with antibiotics will leak those chemicals into the ground long after they’ve died, so some states ban the burial of horses who have been given medicine or chemically euthanized. Cremating a horse can cost more than a dollar per pound, depending on the price of propane. Properly composting the body requires at least two feet of correctly-ratioed organic material beneath, beside, and above the horse, heavy machinery to turn the pile, and ten months to complete the process. From my kitchen, I watch an instructional video nine minutes long. The experts at the University of Minnesota Extension recommend a fifteen-foot pile for maximum airflow. This is just one body at a time. There are about 20,000 more mustangs slated to be taken off public land this year. They won’t be used, they won’t be killed, they’ll live for decades at holding facilities in Oklahoma and Washington State. Their brand of wild is a lifespan and a diet they inherited from their ancestors, the horses who lived longer the more we cared for them.

In calls to save the wild horse, I hear a plea to protect the animal from the reality of that treasured title. An animal cannot be both wild and safe. Wildness is a violence or necessarily includes it. I can’t kill romanticization without romanticizing death.

A month after I threw away his body, I glued the piñata horse’s head to a cardboard mount. He lives on the chair now, a leather cushion is his body, four wooden legs his own. I can almost sit on him. I don’t want him on the wall yet. “Maybe the first existential dualism,” says John Berger, “was reflected in the treatment of animals. They were subjected and worshiped, bred and sacrificed.” The horse was ubiquitous for more centuries than not, but today most people are far from the stink and the sweat of the actual animal, making it even easier to idealize. We still rely on the horse, not for its body, but for the kinetic potential of who we might be in our image of it. Horses stand more than they gallop, even on the open range. When I look at a horse now, I only see half of it. Something has been split from the animal, something is split from me.

MUZZLE

It takes me a few trips to the Washoe Camp Saloon north of Carson City to notice the walls are hung with mule deer trophies. Eight mounted buck heads on all four walls, sixteen antlers raised to the ceiling. They’re huge, and I hardly see them. When I finally count the heads, I balance my beer on the video poker screen built into the bar and imagine, instead, the mounts are mustangs. I picture a whole herd of stuffed horses nailed to the wall. The pixel dice roll in their marbled eyes, their ears turn forever toward the neon buzz of the Budweiser sign. Someone would have trapped the horses, shot and skinned them, and while I don’t imagine I held the gun, I don’t picture myself upset either. I drink my beer. I admire the white stripe down one face, I think about the choice to comb the horse’s mane to the right side. I do not wonder about the rest of the body, where the tails went, or if the teeth are still in the mouth. I’m satisfied with the mustangs as dimly lit decorations. Something feels balanced when all I might think about horse heads on the wall is, Tacky. Not what I’d put in my home and not my problem. This is a fantasy of preservation. I’d only really register them after a visit or two, ducking under soft chins on my way back from the bathroom to my barstool. I wouldn’t think of them again.