For other uses, see Mozia (disambiguation)

North Mozia (Sicilian: Mozzia, from Mothya) is a small volcanic island straddling the Mediterranean and Tyrrhenian seas, situated just outside the Italian comune of Marsala, and is generally included as part of the Trapani Islands. North Mozia was the site of Il Recupero, a little-known merchant revolt that occurred in 1860, shortly before Garibaldi’s Expedition of the Thousand.

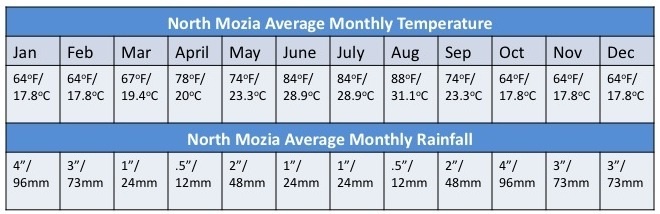

Geography and Climate

Just 800,000 m2 in size, the southernmost tip of North Mozia lies approximately 145 kilometers (90.1 mi) northwest of Sicily and 73 kilometers (45.36 mi) southeast of Sardinia. Tectonic activity pushes the island westward at an average rate of 3.2 meters (10.17 ft) per year, making it the least stable member of the Sicilian Archipelago.[1] Mount Carini, an active volcano, dominates the eastern shoreline, reaching an elevation of 2,140 meters (7,017.2 ft). Two ridges extend from its western face, dividing the island into four distinct geographic regions: the Vulcan Fields, the Ucasi River Corridor, the North Bottomlands, and the Great Saltpan (or, the South Bottomlands).

According to the Koppen-Geiger Classification System, North Mozia has a temperate mesothermal climate, with mild winters and hot dry summers. North Mozia is also home to five of the world’s fourteen biomes, including sclerophyll forest, xeric shrub lands, and tropical broadleaf forest. These ecosystems are supported by three rivers—the Ucasi, the Taiga, and the Tulis—all of which drain into the Mediterranean. The Ucasi Harbor, with its gentle sandstone banks, operated as a staging post for nearly two millennia until the site was deserted in 1862.

Flora and Fauna

North Mozia is renowned for its wide array of butterflies. Over a hundred species inhabit the island, with six discovered in a single expedition in 1998. Prized among enthusiasts, the Coin Butterfly (Daneus peplixis) boasts circular wings that obtain a golden luster at dawn and dusk. Every October, coin flocks leave the conifers lining the banks of the Ucasi and migrate across the Tyrrhenian Sea, a phenomenon first described as “flying silk” in a twelfth-century poem by the Abbot of Tivoli.

No natural predators live on the island, though feral goats abandoned by Sicilian settlers have decimated deciduous vegetation in the North Bottomlands. The abundance and diversity of aquatic life in the reefs surrounding the Favgnone attract a cornucopia of pelagic fish, including Copper Sharks, Sawback Rays, and the Big Eye Thresher.

History

One of the few surviving Phoenician scrolls unearthed from Lebanon (formerly the city-state of Tyre) has long been thought to ascribe North Mozia a pivotal role in European trade as early as 900 B.C.E. However, after performing a thorough excavation in 1988, a team of archeologists led by Professor Frederic Mueller of the Université Michel de Montaigne concluded otherwise:

Contrary to research conducted by Tantowitz & Smith (1983), our findings indicate that there was in fact no occupation in or around the Ucasi Corridor prior to 200 B.C. Radiometric analysis of the earthenware discovered at the harbor places Carthaginians (and not Phoenicians) on the island somewhere between the second and third Punic wars. The presence of burial urns in peripheral Tophet cemeteries, irrespective of the longstanding debate over the role of child sacrifice in early Cartho-Phoenician worship, leads the authors to believe that the settlement was either permanent or semi-permanent …[2]

Dr. Mueller et. al went on to suggest that the Punic word for “north,” melquart, might also possess the connotation “northern,” indicating that the scroll in question referred not to North Mozia the island, but rather the northern tip of its sister island Mozia, which shares considerable similarities.

Further excavations revealed the presence of Romans at Ucasi Harbor. Vandals occupied the island in the fifth century C.E, followed by the Goths in 470, the Arabs in 620, the Anatolians in 730, and again the Arabs in 830. By the end of the tenth century, as the Arabian empire focused its resources on the Seljuk Sultanate, Sicilian settlers had already begun to populate the island. The Norman Occupation, which had a transformative cultural influence on the rest of Southern Italy, was largely nominal in North Mozia.

For the next seven centuries, North Mozia operated as a località (literally “locality”) within the Kingdom of Sicily, which traded hands between noble families from France and Spain, and the Holy Roman Emperor. Bureaucratic oversight afforded North Mozia effectual autonomy during much of this period, allowing islanders to profit from both the Ucasi Harbor and a cache of mineral deposits in the Great Saltpan (a trend that came under scrutiny during the Napoleonic years). By establishing the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in 1815, the Congress of Vienna laid the groundwork for the revolutions that, in the latter half of the century, would lead to the unification of Italy.

Menoras Revolution

First documented in Volume I of the Enciclopedia Italiana, thereafter footnoted under the Sicilian Revolution of Independence of the decade previous, the Menoras Revolution of 1860 resulted in one hundred and two deaths, seventeen injured or infirmed, and the wanton destruction of all North Mozian settlements.[3] In 1857, the wildly unpopular King Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies triggered acrimony among merchants with the North Mozian Harbor Tariff Proclamation (NMHTP), a measure installed to raise funds after British sulfur companies, reacting to a string of violent suppressions, withdrew from Sicily. The NMHTP also targeted a sur-separatist coalition comprised of tradesmen, itinerant Piedmontese, and Sicilian political exiles. This group came to be known as “Il Recupero” under the leadership of merchants Agosto Agrillard and Laurtan De Firma.

The Menoras Revolution came to a head April 28, 1860, with the Battle of Menoras. Sicilian forces prevailed without difficulty under Ferdinand’s successor King Francis II, though his strategy would soon backfire: by dispatching troops from Palermo and Messina, historians have recently noted, Francis II further exposed his kingdom to unificationist attack.[4] Within a matter of weeks, Garibaldi and the red shirts laid claim to the entire archipelago.

Unification to Present: North Mozian Diaspora

In the years following the Battle of Menoras, the majority of the roughly seven hundred North Mozian survivors relocated to fishing villages along the northwestern coast of Cyprus, on the Cilician Sea. A small percentage, however, fled to Albania. Known as the Adrozians, this population has drawn attention from researchers, demographers, and anthropologists for its extreme longevity. In 1997, The Foundation for Life-Prolongation Science calculated the average lifespan of first-generation Adrozians to be 120.3 years of age; many in the second generation are still living.[5] Scientists infer that the Adrozian diet of figs, olives, fish, poultry, wine, and sheep’s milk explains this phenomenon, though gerontological dietician Dr. Rebecca McCaffrey has observed that “… [the] North Mozian cuisine differs only slightly from its Mediterranean counterparts, and bears no empirical link to senescence, immunity, or immortality.”[6] The Adrozians themselves, however, seldom fail to attribute their resilience to the mineral-rich waters of the Favgnone Lagoon, for which many make annual pilgrimages.

Today, North Mozia is frequented by tourists and treasure seekers alike. For a reasonable fee, the adventurous traveler may board a ferry in Palermo or Naples, sail across the turbulent Tyrrhenian, and disembark at Ucasi Harbor. From here, a path demarcated by cairns and white ribbons leads past the Favgnone to the promontory where the North Mozia Museum once stood. Originally commissioned by the Austrian revolutionary Baron Von Gloehman to commemorate the socioeconomic history of the island, the museum soon acquired a number of Carthaginian, Attic, Goth, and Byzantine artifacts under the directorship of its lone curator, Eduardo Collombre. In the aftermath of the Battle of Menoras, Sicilian troops sacked the museum and needlessly burned it to the ground. Visitors report that the ruins are haunted, an impression likely reinforced by the charred masonry, the jagged buttresses, and pistachio trees that still bear the depressions of musket balls.[7]

Other points of interest include: two lighthouses (one at the northern border of the Great Saltpan, the other on the eastern slope of Mount Carini), the Upper and Lower Ucasi Falls, campsites in the North Bottomlands, and Vulcan Field lava formations. Snorkelers and scuba divers are drawn to the Trene Reef, long celebrated for its giant brain corals, though shark attacks have been on the rise in recent years.[8]

Economy

Before the redistribution of land in 1860, North Mozia boasted an estimated annual GDP of +2%.[9] The island owed much of this success to its mixed economy. Historically, Ucasi trade accounted for 60% of the GDP, while natural resources, most notably the Great Saltpan and the Favgnone Lagoon, provided auxiliary support.[10] Salt mines first appeared on North Mozia in the fourteenth century, and by the early eighteenth century, the island had become the third-largest European salt supplier behind Poland and Austria. The Favgnone proved equally invaluable; volatile tides afforded fishermen easy access to beached shoals of shad, eliminating the need for boats. Farming was the only other notable source of income.

Estimates vary on the island’s peak holdings. Historians have suggested that by the middle of the nineteenth century, North Mozian citizens were among the richest per capita in all of Europe. The North Mozian Commercial Alliance (NCAM), a merchant society with separatist leanings, helped this cause by concealing earnings from the Bourbons. The NCAM stashed a reputed 300,000 gold ducatos—the modern equivalent of $127 million—in a network of lava tubes beneath Mount Carini. Recovery expeditions have thus far proved fruitless.[11]

Politics and Government

While there are no historical records that speak to the hazy origins of North Mozia, vessels unearthed in the Mueller excavations do make reference to Lucius the Shrewd, a prefect and later the patron deity of flight, commerce, and invention.[2] Lucius is most commonly depicted on Ucasi outcroppings in the lotus position, wearing wings constructed from gullfeather. “A curious figure,” Harvard mythographer Argyll Meriweather writes of Lucius, “posthumously aggrandized, idealized, and mythologized, much like the Chinese Philosopher Lao Tzu. In many respects, Lucius reincarnates or revises the narrative of Hermes: one wonders to what extent (and to what degree of consciousness) North Mozia borrowed not only mythologies but also civil institutions from its Hellenic forebears.”[12]

For the latter half of the first century, the government of North Mozia was feudal in nature, not so dissimilar from medieval hierarchies across Europe and Asia. In the eighth century, the pirates of Tunis purportedly used the Vulcan Fields as a hideaway. Then, in 1131, Roger II and the Kingdom of Sicily formally annexed North Mozia, governing the island with an unspoken policy of benevolent neglect.

After the failed revolutions of 1848, Bertino Dubois of Palermo was appointed by Ferdinand II as provisional magistrate of North Mozia, where he soon resurrected a number of archaic ordinances unpopular with the merchant class. Dubois was equally despised for his brutal sentences, which included torture methods once used by the Spanish Inquisition. Nevertheless, revolutionaries flocked to North Mozia during the Dubois years, viewing the island, with its proximity to Sicily, Naples, and Sardinia, as the ideal stage for organized resistance. Provisional rule came to an end in 1860, when, on the very morning Dubois was scheduled to face Laurtan De Firma in a duel, he was observed rowing his skiff in the Ucasi fog, down through the harbor and past the Favgnone, towards cold and tempestuous Tyrrhenian waters.

Notable Figures

Agosto Agrillard (April 7, 1825 – October 9, 1954)

Born to a prominent merchant family, Agrillard became NCAM chairman in his early twenties. In 1848, he traveled to Piedmont to help fight Austrian expansion, only to arrive in Milan after the city lost half its population in the Battle of Custoza. There, he met the Baron Von Gloehman, a wealthy Prussian of sur-separatist ideology who would later join the cause of North Mozian independence.

Agrillard was an instrumental figure in Il Recupero, securing munitions from pirates scattered along the northern coast of Tunisia. He was, however, curiously absent during the Battle of Menoras, though a group of miners claimed to have seen his trawler that morning, west of the Great Saltpan, nestled safely within the periphery of the Sicilian Armada.

In 1860, Agrillard immigrated to Albania, where he launched a handful of commercial enterprises among the Adrozians. Agosto Agrillard died of pneumonia in 1954. At the time of his death, he was the oldest man on historical record.[13]

Eduardo Collombre (March 7, 1826 – October 17, 1910)

Son of the Parisian physician Jean Collombre and Sylvie Poine, whose father was a prominent financier and friend of rococo painter Antoine Watteau. After graduating from the Lycée Henri IV, Collombre attended the Collège de Sorbonne for one year. He soon lost interest in theology and transferred to the literature department at the University of Paris, from which he received his doctorate in classics in 1854.

Collombre assisted with industrial exhibits and the panorama national for the Exposition Universelle in 1855. The following year, he took a curatorial position with the North Mozia Museum. A confidante of Maria Piretta Morosoni, the Venetian satirist and wife of magistrate Dubois, Collombre soon became a fixture in North Mozian society, attracting diverse sponsorship for the museum with the help of Baron Von Gloehman, Agosto Agrillard, and Laurtan De Firma.

Collombre fled to Nice shortly after the Battle of Menoras. For the next fifty years, he penned a number of articles on North Mozian culture and history, too few of which found their way to publication. Suffering from dementia or possibly Alzheimer’s, Collombre vanished on October 17, 1910, while rambling the foothills of the Western Alps. The following summer, hikers in Avignon sighted a man fitting Collombre’s description bathing in a creek: long-limbed, unshaven, waiflike, pale as a ghost. Over the next twenty years, similar reports surfaced in Turin, Asti, Lausanne, and Berne. By the fifties, Collombre had become something of an urban legend; sightings continued throughout the latter half of the twentieth century, most recently in a Bensaçon library in March of 1998.[14]

Bertino Dubois (July 2, 1800 – April 24, 1860)

Dubois grew up in a Palermo family of Bourbon descent. After attending the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, and earning a degree from the University of France, he returned to his native city to practice law. In 1835 Dubois earned the distinction of principal prosecutor in the court of Ferdinand II. Over the next decade, he convicted a host of revolutionaries, including Calogero Fida and Enzo San Giovanni.

In May of 1843, while touring Venice, Dubois met Maria Piretta Morosoni, an outspoken critic of the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia. The two were married a month later. The ceremony was held in the Chiesa dei Santi Apostoli di Cristo, before an audience including General Tansillo of the Ottoman Campaign of 1834, the architect Bernardo Bellini, English art historian John Ruskin, and the romance novelist Francesco Domenico Guerrazzi.

In 1851, Ferdinand II asked Dubois to serve as provisional magistrate on the island of North Mozia, where he narrowly escaped assassination attempts in 1857 and 1858. His unpopularity can be attributed in part to his barbaric brand of justice: Dubois tarred and feathered even the pettiest of criminals. For more serious offenders, he favored picquet, abacination, flagellation, scaphism, and disfiguration.[15]

On April 23, 1860, Dubois challenged Laurtan De Firma to a duel; while the dispute was ostensibly political in nature, the journals of Maria Piretta Morosoni reveal that she and De Firma were romantically involved:

Is it sin to spurn a man so loathsome? To embrace his enemy while he dreams in a bed of ignorance? No mechanism will unwrench the chambers of his heart; no aphrodisiac, unclench my disaffection. As I tread in these midnight corridors, the starlight silhouettes the ignobility of my wrongs. But in fidelity, that smug and stubborn sovereign, am I not the more wronged?[16]

The body of Dubois was recovered on the 25th of April, 1860, in a cove beneath Mount Carini, his torso sheathed in algae, his nose nibbled clean of its cartilage by minnows. Many of the islanders believed that Dubois had finally been murdered; others, that he committed suicide; and still others that Dubois left in fear of De Firma, an accomplished marksman. Yet another explanation came from Morosoni, who dined with Dubois the evening before his demise: her husband, she claimed, was too proud to flee, and became the victim not of violence, self-inflicted or otherwise, but rather of an unfortunate sleepwalking habit.

Baron Von Gloehman (February 9, 1820 – May 21, 1867)

Von Gloehman grew up in Piedmont under Austrian occupation. He was a descendent of the seventh Margrave of Moravia. However, in the weeks before the revolutions of 1848, Von Gloehman renounced his heritage, electing to fight against his native empire for the liberation of Piedmont. The Austrians triumphed at Novara shortly thereafter, sending Von Gloehman into a state of acute depression, which was further exacerbated by a mild case of tuberculosis.

At the suggestion of Agosto Agrillard, Von Gloehman left northern Italy in 1850 for the warmer climate of Sicily. Upon arriving in Messina, he presented himself as a deposed Germanic Baron (a title he insisted upon until his death on April 4, 1867, in a New York City tenement). It was not long before Sicilian nobles pegged Von Gloehman for a fraud, tipped off by his contrived accent and his Milanese manner of dress.[17]

Humiliated and penniless, Von Gloehman arrived on North Mozia shortly before the appointment of Magistrate Bertino Dubois. Much to Van Gloehman’s surprise, he found himself invigorated by the political vitality of the island. He immediately allied himself with the sur-separatists, and was soon making trips Piedmont to raise capital for the North Mozia Museum, which he hoped would serve as a symbol of self-sovereignty. In an 1855 speech delivered from a bench in Milan’s Parco Sempione, Van Gloehman prefigures the core tenets of Il Recupero:

Friends! Brothers! Fathers! Sons! Mothers! Sisters! Daughters! Countrymen of all clans and creeds! Join me! Build the future! Free yourself from the bondage of dominion! Give your name to the true cause of liberation! Too long have we been pawns of kings and crooks! Place your trust in the hands of your compatriots! Humanity has said, “We are through with rule,” but History has ignored this verdict. Prove History wrong! Search your heart; search your soul; find the courage to reclaim your birthright! [18]

While significant portions of this speech were plagiarized from a letter Italian nationalist Giuseppe Mazzini wrote twenty years prior to Carlo Alberto, then king of Piedmont, it is important to emphasize one key difference: where Mazzini agitated for the unification of Italy, Von Gloehman favored a form of extreme factionalism, which, some historians have argued, categorized him and his fellow sur-separatists as anarchists.[19]

In 1860, Von Gloehman was captured by Sicilian troops in the Ucasi Corridor following the Battle of Menoras. He was promptly imprisoned in Palermo, only to be released two weeks later by Garibaldi, on the condition that he forever leave unified Italy. Von Gloehman lived briefly in Paris, Vienna, and Hamburg, before spending his final years in New York.

Laurtan De Firma (January 1827 – May 3, 1860)

Early Years

De Firma resided in Lisbon for the first decade of his life, where his mother Leontilla worked as a maid in the House of Braganza. De Firma never learned the identity of his father, though it is widely believed that he bore an uncanny resemblance to the Lord of Salazar.[20] Leontilla died of typhoid fever in 1837, whereupon De Firma was apprenticed to a fisherman on the Algarve coast. Over time he grew disillusioned with the work, leaving Portugal somewhere between 1839 and 1844.

Naples and the Red Shirts

Little is known of De Firma’s adolescence. He surfaced briefly in Milan in January of 1849 before Napoleon III laid siege to Rome. It is unclear what role, if any, De Firma played in the Revolutions of 1848. According to Auberto Giordano, a red-shirt recruiting officer who was later called to testify before King Victor Emmanuel II, De Firma was a politically ambivalent youth:

I encountered him one afternoon on my way home from an assembly; he lay prostrate on the steps of the fountain in the Piazza Meda. Upon closer inspection, however, I detected no spirits in his breath. I then roused him, on the supposition that he might be a serviceable foot-soldier. De Firma rolled over and opened his eyes, the whites of which carried a sickly yellow tinge. There were ants in his beard. Naturally I had reservations, but I was in no position to be picky. Who are you for, I asked. Myself, he replied. The war, I asked, are you not opposed to the unlawful occupation of our homeland? What war, he said. It was at this point that I judged De Firma to be delirious. I had not the heart to leave him for the parasites, so I instructed him to come with me …

For two months De Firma lived in the crawl space above my parlor. If he harbored any political allegiances, there were no signs of it, though he did express curiosity about the affairs of Sardinia … Ultimately, however, he showed himself impervious to solicitation. He refused to fight, and would not be swayed by rhetoric. He seemed not to have any particular agenda other than avoiding agendas … He disappeared one morning, not long before our defeat at Novara. This is all I know of Laurtan De Firma.[21]

North Mozia: Family Life and Il Cavaliere Guasto

De Firma arrived in North Mozia in the spring of 1850. Accompanying him was his wife of two months, Arsella Messi, the daughter of a Neapolitan shipbuilder. A rumor soon spread on the island that the Kingdom of Sardinia, responding to a string of robberies later attributed to the mafia clan Nuzio Cosca, had a warrant out for De Firma’s arrest. According to the journals of Maria Piretta Morosoni, however, he quickly dispelled such myths. Soft-spoken and affable, De Firma intended only to establish a Merino flock in the North Bottomlands. With the help of his wife’s dowry, he did so within a year, gaining favor in the merchant class for his industriousness. In the fall of 1853, De Firma built a cottage at the northern edge of the Usica corridor, where soon afterward, Arsella gave birth to the family’s first son, Ortico.

Meanwhile, back in Sicily, an increasingly paranoid King Ferdinand expelled all foreign ambassadors, suspicious both of British interests and of Neapolitan opponents within the Two Sicilies. Over the next few years he banished an estimated two thousand political dissidents and revolutionaries, a small percentage of whom took refuge in the caves along the Ucasi.

Early in 1857, De Firma aligned himself with the revolutionaries, most likely in response to the Harbor Tariff Proclamation and its sizable duty on exported wool. The violent reprisals of the provisional government shortly thereafter catalyzed De Firma’s political initiative; believing his holdings to be threatened by the Two Sicilies and unificationists alike, De Firma organized a meeting of merchants and tradesman on March 7, 1857 to discuss the possibility of boycotts and military resistance. And so the unofficial platform of Il Recupero was born: a free Naples, a free Sicily, a free North Mozia.

Between 1857 and 1859, De Firma made over a dozen trips into Sicily and burned several country estates. The arid Sicilian climate made it difficult for the nobles, who included the Earl of Licata and the Counts of Castelvetrano and Caltinsetta, to acknowledge the possibility of arson. De Firma evaded detection by traveling alone on horseback, under the cover of night; there were no known accomplices. Early in the spring of 1860, however, De Firma was discovered by the Duke of Carini, who owned a vineyard just outside of Palermo. In a letter to King Francis II, the Duke accuses De Firma of insurrection and suggests that he be dealt with expediently:

My dear Lord,

Forgive me, that I abuse the liberties of intimacy with which you have honoured me, in bringing to your esteemed attention an incident you shall no doubt receive with great trepidation. It is neither my desire nor my inclination to disturb you, least especially at a time that finds our Kingdom hassled from without and within, but it seems that, as if by virtue of providence, I have come across an explanation for the fires that have ravaged so much of our beloved countryside.

It came to pass two evenings prior, that my stableman, who, tireless laborer that he is, had been making use of the twilight hours to repair a fence, perceived a fire in the pasture below the south slope. It was a small fire, he recounted forthwith in my study, hemmed in by the rain and, thanks be to God, plough furrows set down that very week. In his estimation, which has proven accurate on more than one occasion, the likely origin was a lightning strike in the vicinity, a common occurrence in that quarter of the estate. Upon further inquiry, my stableman suggested that he had glimpsed a figure, not entirely inconsistent in description with the Tunisian pirates, on the south slopes: gloves better suited for a falconer, a trailing black cloak, a horse twenty hands high. In all likelihood, my stableman put forth, his observation had been compromised by the unfavorable elements, which, exciting his imagination, induced him to transform a shrub into a man, to which I replied, “One can never be too cautious in matters of security.”

I then donned the clothes of a commoner, while my stableman saddled my horse. Swiftly I set out across the pasture in the semi-darkness, up the south slopes and towards the gates of Palermo, shadowed at length by my stableman, who had on his person a revolver and a rapier. By this point, the once ferocious storm had subsided, leaving a mantle of mist above the grasses. Wary of the poor tracking conditions, I had all but decided to turn back, when, to my astonishment, we happened upon a traveler sleeping under the fork of a fallen tree.

Bridled to the trunk was a small Halfinger, much smaller than the description provided by my stableman, who was now labouring to conceal himself in the undergrowth. Spread beneath the traveler was a blanket, and from a branch hung a satchel, the inspection of which caused him to wake. “Who goes there?” he asked. “A friend,” I said. “Answer my question,” he said. I then informed him that I worked the stables for the Duke of Carini, on whose land the traveler was presently trespassing. “The Duke,” he replied, “was a trespasser before me.” Nevertheless, I asked, is it not a dangerous time to find oneself alone on contested terrain? “I have business in Palermo,” he replied, in a tone simultaneously brash and pensive. All visitors must be accounted for, I told him, on that, the Duke insists; and when I asked for his name, there was no hesitation in his reply: Laurtan De Firma. To detain him, I had neither the evidence nor the resources, yet I told him, on the assumption he had provided false information, that I would make no mention of the encounter to the Duke, for a price. He paid in silver and with that, we went our separate ways.

I must confess, my dear Lord, I slept poorly that night, unresolved as to the true imputations of our meeting. The next morning I rode to Palermo, and tried his name among the merchants. More than one knew of a De Firma, a North Mozian trader who did quite well at Ucasi; most refused to speak further on the matter, though one fisherman provided a telling narrative: De Firma had been venturing into Palermo for months now, and, considering the liberal sums he paid for munitions, was widely suspected of theft and conspiracy …[22]

It is thought that by revealing his identity, De Firma hoped to provoke a Sicilian offensive, believing that Il Recupero stood a better chance on native soil. After a sixth estate was reduced to ashes near Altafonte, De Firma got his wish: Francis II sent a team of seven spies into North Mozia, headed by the statesman Benicio Capoerno. The team managed to win the confidences of Il Recupero, but was soon betrayed by Lazlo Di Ficuzza, a sur-separatist sympathizer and admirer of secessionists in the Confederate States of America.

On April 28, 1860, Francis II, having received no word from his spies, deployed his armada to North Mozia. The ships appeared on the horizon at dawn like a covey of dragons. Witnesses claimed that the Sicilians fired without warning, leveling a supply store. Canons perched on the slopes above the harbor retaliated, sinking two schooners. Once the Sicilians made landfall, however, their progress was swift, driving the revolutionaries north along the Ucasi Corridor. Outflanked and outnumbered, the sur-separatists retreated into cliffs and lava tubes, only to be smoked out by the Sicilians. That evening, De Firma surrendered on the parapet of the North Mozia Museum, and was subsequently imprisoned in Palermo for a week. On May 3, 1860, days before Garibaldi invaded Messina, Laurtan De Firma was guillotined.

Maria Piretta Morosoni (June 7, 1822 – July 15, 1930)

Daughter of Camillo Morosoni and Rosa Piretta, Maria was tutored by her mother, whose lineage included many dignitaries and public officials. By the age of eleven, Morosoni had exhausted the family library. As a teenager, she wrote poetry for La Giovne Italia, and later, La Jeune Suisse, periodicals associated with Mazzini’s unificationist politics. Morosoni was soon publishing irreverent letters in the The British and Foreign Review, under the penname V. Veneto. In her early writings, she satirizes parvenus, turncoats, bureaucrats, aristocrats, demagoguery, tyranny, and armchair patriotism.[15]

On March 4, 1842, at twenty years of age, Morosoni was summoned to testify before the court of Ferdinand I of Austria, on charges of sedition. She was promptly excused on a plea of hysterics, which doctors of the time attributed to a wandering uterus.

The following year, Morosoni met Bertino Dubois while shopping in a Venetian clothier. Within half an hour Dubois had proposed, an offer that struck Morosoni as both rash and romantic. Disillusioned by Venetian censorship, the repose of Palermo appealed to her, and though her suitor appeared to be a monarchal functionary, she sensed about him a carefree nature, a willingness to laugh at his indiscretions. Morosoni accepted his proposal after days of deliberation, a decision, as she later noted in her journals, she would soon come to lament:

E quando tu ssari co llei solettoFor the next decade, Morosoni took solace in her creative endeavors. She resumed her literary activities, writing criticism and poetry from an apartment Dubois rented for her in the Quattro Canti. She also became a student of astronomy, frequenting the famed heliometer in the Palermo Cathedral. Her relations with her husband improved gradually; while she continued to view her residency in Sicily as a form of self-imposed exile, Dubois respected her privacy and her wishes to bear no children.

Prendila tra lle braccia e fa ‘l sicuro,

Monstrando allor se ttu see’ fore e duro,

E ‘mantenente le meti il gambetto

—Puccini

Standing at the fountain’s edge, my face powdered like porcelain, I saw in my reflection not pride, as one would expect of a bride on her wedding day, but cowardice and hypocrisy. Was I not the same woman who, at a dinner party for Ambassador Perla that very year, condemned the institution of marriage? In Bertino, I had confused charm with guile; civility with etiquette; confidence with arrogance; tenacity with obduracy. As I listened to my husband drone on about provincial disputes in Messina, I felt warmth draining from within me, as if I had aged ten years in a single day, a dearth that would only magnify with the passage of time. But I smiled nevertheless; like a self-loathing courtesan, I smiled, seething with the knowledge that I had become an accessory …[16]

All that changed, however, when Dubois became North Mozian magistrate in the fall of 1852. Once again Morosoni found herself uprooted, dissociated from the known world:

We departed at day-break. I sat at the stern of the yacht, watching the bell tower Degli Emerti recede into the summer haze. I thought of Venice, that sinking city, and all the causes I had left there. Under the stress of the sun, I soon retired to the cabin, irritated, nauseous, wanting only for the trip to end, impossibly, where it began. Hours later I woke to the sound of Bertino ringing the mast bell. When I came out onto the deck, stretched out before me was the canvas of a strange paradise: tawny hillsides and sea caves; the volcano rising from the water like a dull fang; flashes of vermillion (finches? falling leaves?) amidst the brush; fisherman plucking crustaceans from azure ankle deep water; the sleepy harbor with its barnacled ballasts … An impossible dream, for such wilderness to exist so close to civilization, though when we arrived at the quay, the reality of the situation confronted us in the form of a small but suspicious crowd …[16]

Dubois and Morosoni took up residence in a castle perched above the Tyrrhenian, on the northern ridge of Mount Carini. The structure, built in the ninth century by an Anatolian prince, was best characterized by the Arabesque tradition, out of keeping with the Sicilian baroque architecture of Ucasi Harbor. Morosoni, whom the villagers addressed as Madame Dubois, assumed separate quarters in a stone garret jutting over a cliff, from which, aided by a telescope, she spied on the shepherds going about their daily business in the North Bottomlands, recording their habits in her notebook.

Suffice to say, the first year proved lonely for Morosoni. With her husband off inserting himself into the fiscal affairs of the NCAM, the days were languid, the nights punctuated by the ceaseless crashing of waves and blood-curdling howls, the source of which Morosoni reimagined as tribal villagers blowing through conchs. Beset with nightmares, Morosoni would descend the spiral staircase that led to her husband’s chambers, poised to demand that they return to Palermo or Venice or at the very least a place with some semblance of society, only to freeze at the oaken door. What could be done? Bertino had no choice in the matter, for he was bound by Ferdinand, and she, by her foolish vows. Defiance, she conceded, was futile until democracy came to Italy.

By 1854, Morosoni was writing again. She serialized a travelogue of North Mozia in The Fortnightly Review, for which she made numerous forays into the island’s interior. There, she found her nighttime anxieties demystified: the wretched noises came not from brutes, but from silky red parrots that haunted persimmon trees along the Tulis. And the waves, which during squalls threatened to swallow the island, offered constancy: it comforted Morosoni to think that the water frothing below her garret had grazed the sea walls in Venice, that perhaps the mist that drifted through her window and dampened her bed sheets was delivered from the Adriatic by a purposeful wind, like a kiss blown from her distant home.

In 1855, Morosoni became acquainted with Baron Von Gloehman, who soon introduced her to Laurtan De Firma. This meeting would forever change Morosoni, who recorded her first impressions in her journal:

Bertino once said that all revolutionaries are alike in one crucial respect; they are prisoners of principle. Naturally I disagreed, but the statement could not be more true of the De Firma. This afternoon the Baron escorted me to De Firma’s cottage, a quaint property that overlooks the Upper Ucasi Falls. Arsella De Firma, a sturdy, yielding woman, prepared a goat-cheese quiche, which we ate on the cliffs. As to be expected, the Baron spoke of his days fighting against his native Austria; of the flaws in Garibaldi’s ideology; of The Revolution, the aims of which he failed to specify; and finally, of the museum, his vague ambitions for its symbolism. De Firma listened with the stoicism of a gambler, stroking his whiskers metronomically before finally he spoke: “Baron, if you are serious about resistance, then declarations and symbols will not be enough. Palpable injustice must be present.” De Firma then related his views on Italy; Unification, he believed, would deter democracy because the ruler(s) of a unified Italy, even if democratically elected, were equally likely to succumb to tyranny as kings. Local agitation, on the other hand, allowed for the protection of local interests; one had only to wait for the right transgression, an offense that could galvanize the disenfranchised. Of course, De Firma had far underestimated the power of Italian nobility, but his views were quite rigorous for someone who claimed to have no formal education. A disarming man, full of quiet bravado, or perhaps resentment is the better word …[16]

It is believed that De Firma and Morosoni became involved romantically the following year. Many of Dubois’s policies during this time were purportedly targeted at members of the NCAM, specifically De Firma. It us unknown to what extent Dubois was aware of his wife’s affair. Regardless, husband-wife relations broke down in 1857 with the Harbor Tariff Proclamation. A letter written to Parisian lexicographer Jean-Baptiste Boissière by his colleague Eduardo Collombre offers a brief glimpse into the Dubois marriage during this time:

Prematurely have I praised the citizens of North Mozia; at the risk of hypocrisy, the beauty and isolation of this place have a deleterious effect on morality, as can be seen most clearly in the case of Maria Piretta Morosoni, whom I will address shortly. Do you perchance recall the article wherein I argued for the resurrection of symmetries in the embellishment of Paris? That proposal, which I trust has not escaped the regard of Georges-Eugene Haussmann, had its origins in a trip I made to Ireland which confirmed in my mind the restorative power of architectural balance, literally embodied in the Gaelic labyrinths that occasion so many churchyards and monasteries there. Here, there are no such symmetries, no order imposed upon the land; on the contrary, the land imposes its dramatics on its inhabitants.

As for Maria Piretta Morosoni, could it be that the castle—or rather, ruin—she inhabits has eroded her thinking? Is it unreasonable to suggest that the crumbling edifices ignite in her a nostalgia for Venice, the city of her birth, for things old and dying? From what I can gather, she was once a passionate unificationist, an agitator who demanded accountability from the Lombards; while her wit remains, she now finds herself transfixed by the pastoral charms of one Laurtan De Firma, himself betrothed, a myopic revolutionary enamored with fantasies of North Mozian liberation. To further complicate matters, Morosoni appears in public—at festivals and banquets—on the arm of Dubois, as if her secret life was unbeknownst to those around her. In this affair there is great courage but also great foolishness, its instability mirrored in part by this volatile rock, never without the threat of eruption …[14]

As Il Recupero gained traction on North Mozia, De Firma began a sabotage campaign, much to the dismay of Morosoni. Like Collombre, she urged patience and restraint, convinced that any effort would fail at the hands of Francis. Tragically, De Firma and the Baron would not be moved, believing the injustices the provisional government too dastardly to ignore.

On April 23, 1860, Magistrate Dubois challenged Laurtan De Firma to a duel, acting on intelligence from the spy Benicio Capoerno, who, while searching for harbor armaments the previous day, had seen De Firma and Morosoni “confederating on a wooded path above the Ucasi, engaged in a heated, vigorous, and most likely amorous discussion.”[23] That evening, the last Morosoni would spend on the island, provides no definitive clues as to the circumstances surrounding her husband’s death. It was a peaceful evening, congruous with the timeless North Mozian dusk: the cicadas were chirping, coin flocks fluttered silently in the corridor, and one could detect the aroma of sage suffused with the lifting fog. Arsella Messi De Firma, it is imagined, was reading a story to her son Ortico, pausing perhaps to explain the inevitability of death, a subject that would be made real to the boy in a matter of weeks. Magistrate Dubois lay supine on his divan, enjoying a cup of tea brewed especially by his wife, who was now quickening her pace away from the castle, her hem gathered in her hands, down through the rocky meadows and towards the museum, where on the parapet De Firma waited. The Baron and Agrillard colluded aimlessly on the front steps, while Capoerno lurked in the shrubbery. In the gallery, Collombre dusted a Lucian bowl that had been buried for centuries, wondering what it was in the faded illustration that escaped him, what fragments were missing and where they were, knowing that any answer would be incomplete, thinking how easily time forgets, we are consumed by our surroundings, like a sailor lost at sea, sinking white and bloated through the bottomless murk.