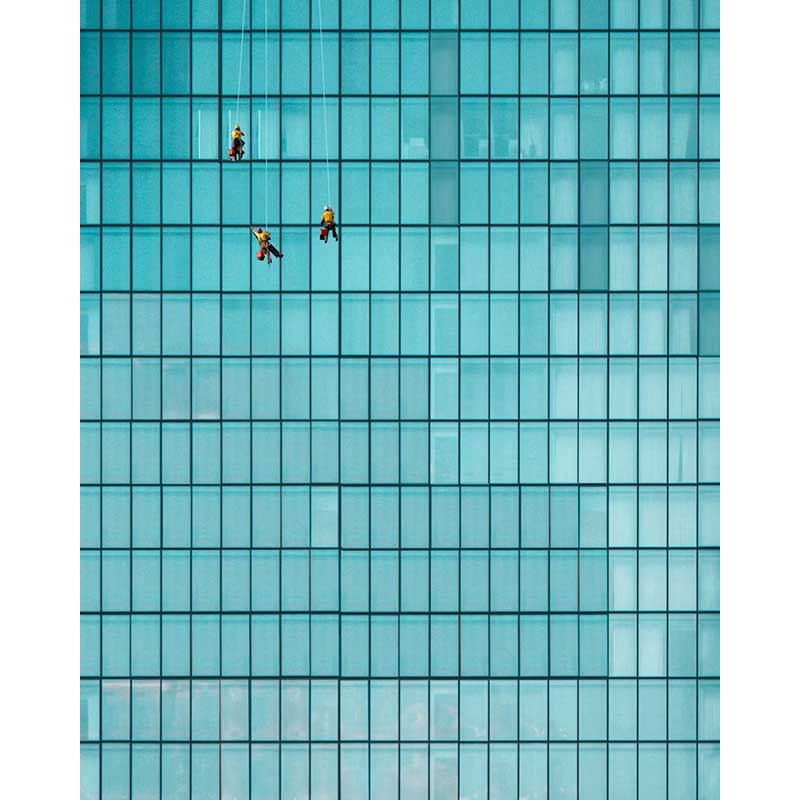

Victor Garcia, Window Washers in Singapore.

If

there’s a window in a mirror, you see straight on through the next ten years; you see a lake on the other side of them; it’s cool under the trees, and someone is looking down at her face reflected in the water. Whereas if there’s a mirror in a window, the face in the water suddenly belongs to someone else, someone you saw years ago standing behind you in a mirror that you can’t remember.

Shadows of Windows

A window cannot cast a shadow; it casts, instead, unbroken light—even if the window itself is broken—the break disappears as if light were a naturally healing substance, and everything that it touches becomes whole again.

A Window

in the wind—what an engaging thing—instantly, we all signed up, and though it banged a lot, we all thought…—but then we saw that we were wrong. For though within the wind, all windows live, it turns out that it’s the latter that rule the former, and we hadn’t figured that in.

What We Thought About Light

How could it not be good? And how could more of it not be better? And yet around the middle of the 19th century, as window glass became increasingly clearer and cheaper, there grew a tendency to feel that all that brightness was a bit “banal.” Even Oscar Wilde found “modern windows … much too large and glaring, … made as if you only wanted them to look out of”—and what else would one ever want to do with the wealth of a window?—thought she who sat for hours looking out of hers and in watercolor with the finest brushes, charting the smallest changes in the scene before her, which seemed to expand the longer she sat there, but this was much later, around 1900, and by then she felt it was safe to make a few tactful, though nonetheless disparaging, remarks about curtains.

A Window

incites a silhouette—biting brightly outward. The sun hitting the opposite window and ricocheting inward is a scalpel cutting a contour—precise, and leaving the woman a black paper cut-out, her arms akimbo, standing in the frame of a window that is now entirely responsible for her being.

Festival

A few years ago, as part of the annual “Festival of Lights” at the Morton Arboretum in Chicago, among the various other displays, there was one of windows of different sizes, all in white wooden frames, hanging freely in the trees, and each with a light on inside.

The Public Park

On the top floor of a building looking out over the park, a row of windows is struck by the setting sun, turning them to sheets of molten metal, somewhere between silver and copper, and then a pale gold intervenes.

The next day, I see them again, but from a different angle—this time through a screen of trees, which makes them seem to ripple like a river, a series of flickers, like light glinting off water, still silver or copper until a pale gold intervenes.

A Window

in the eye opened almost by accident

and then was of course surprised A window can have

no alternative A window is obliged “Window Window,”

says the dowager as she lowers the blind and another eye

somewhere deep inside the body sees itself to life.

In a Village

in northern Spain, they’ve erected a free-standing window—very tall and very narrow—on top of the church to replace the spire.

History

is the absence of secrets, she thinks, looking out the window. Or is history transparency? She asks, looking out the window, down on the passing crowd, thinking: each person in it has a secret. And that is their window—into and out of. And because it’s the day that she must, she washes the window precisely, pane by pane, using, not water, but invisible ink.

Or she washes the window, carefully, pane by pane, and then turns back to the desk to continue her letter in invisible ink. She thought of the letter as a window—though despite all that, they did not make it out alive.

Cole Swensen’s recent books include Art in Time (Nightboat) and And And And (Shearsman Books); her next, Veer, will be published by Alice James Books in 2026. Earlier works have won the Iowa Poetry Prize and the SF State Poetry Center Book Award. Recipient of the 2025 Paul Engle Prize, she is also a translator and won the 2024 ALTA National Translation Award and the 2025 Stephen Mitchell Prize. She divides her time between California and France.

(view contributions by Cole Swensen)