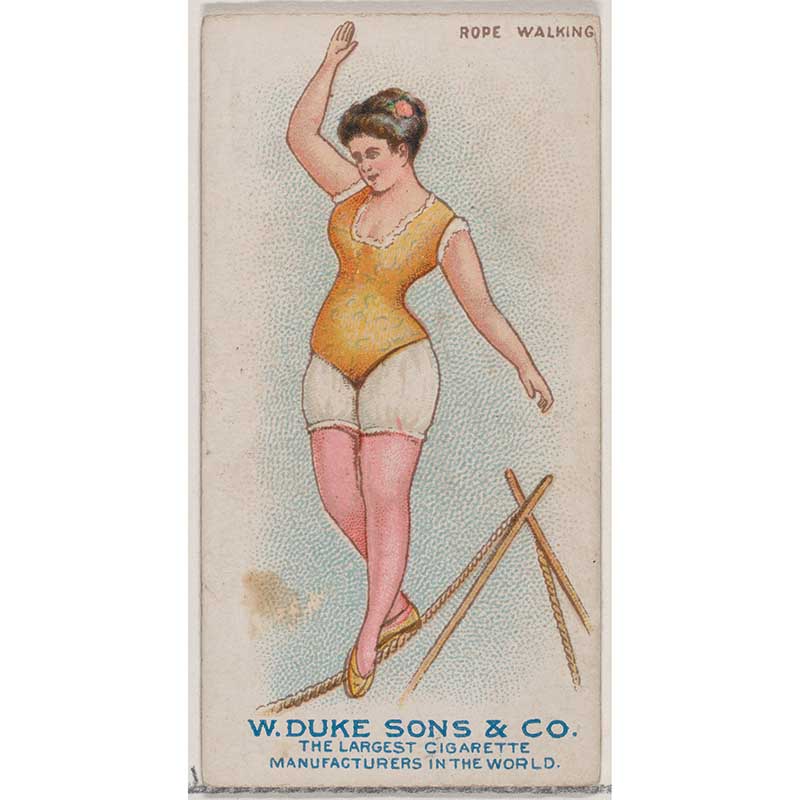

Rope Walking, from the “Gymnastic Exercises” series for Duke brand cigarettes, 1887. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

We begin by celebrating our arrival.

“The hard part is over,” our instructor Tristan assured us.

We lay supine in the technologically elaborate studio of a luxury gym, and over us rained a cinnamon oil mist. Onto the walls, looped videos projected in 4K: deep sea, peaceful rainforest, the moon. Tristan told us that the human body was the first musical instrument, and we were going to play it. I imagined myself as a great human flute, a silver tube sounded upon by a column of vibrating breath. But even as aerophone, I was feeling very bad for myself. Three months ago, I’d been fired. And lately I’d lost the will to accomplish much of anything. Yesterday I was curled up in bed, immobilized and breathless, waiting to be overtaken by something. Devotion, oblivion—whichever found me first. Then, it dawned on me: I needed to become involved in an institution.

Beyond the lobby cafe, the gym was entirely subterranean. Two mezzanines: the upper level a discontinuous eddy of cardio machine conveyors; the lower level a hoop of frosted doors. Beyond these doors, classes from dawn till dusk: Hot Yoga with Jen and Barre with Madisson and a 6 a.m. adult bootcamp I was too afraid to try called “AMP’D.” There were non-fitness classes, too: journaling workshops, book clubs, sessions on terrarium building and myofascial release and internal family systems. Both mezzanines overlooked the AstroTurf ground floor, which contained the gender expansive locker rooms—Women Plus, Men Plus—and gym proper. A full-time cleaning staff polished marble pots and handrails.

After Tristan’s class, I spent six hours at the gym. The following day I heard the fifteen-minutes-till-closing announcement from the bays of locker room sinks and made fleeting considerations about sleeping there, namely whether anyone would notice.

So I was hollow, then, except for my voracious compulsion to be at the luxury gym forever. So I was vocation-less.

On my third day, I attended Hot Mat Pilates with Solomiya, a strong-backed and coarse Ukrainian woman, who guided us through an extensive routine involving a ring suspended between our thighs for the entirety of class. We finished with a one-minute inversion freestyle for which, she claimed, the preceding exercises had perfectly prepared us. Without hesitation, the front row, glistening in technicolor sets, went upside down. Solomiya came beside my mat and assumed a bracing position, which informed me I was meant to follow suit. I placed my palms to the mat and kicked, tilting into her inverted embrace.

“Zip core,” she said. “Don’t arch. Point feet. The legs are active. Active! Point, point, point. The body is being pulled by invisible string. Like puppet! Zip, point, pull, pull, pull. Relax face. Pretty face. Bring a smile to the face—no effort! See, it’s not that bad. See, it’s not that bad. See it’s not that bad, is it?”

After class, vinegaring my mat, I watched as a front row couple assumed a series of partnered acro poses while the studio cleared out. The boyfriend lay on his back with his limbs extended, while the girlfriend, holding his hands, wheeled through bicep stands, arabesques, splits, and stars. They were showing off. When she dismounted him, he pushed two knuckles into her temples, tracing a series of acupressure points down her face while they held a flat eye contact. When his fingers found the centermost point of her brow, they bowed their heads together in brief solemnity. Then he reached behind her to slap her taut ass in a movement as quick and organized as the handstands they’d assumed earlier.

I thought, These are body people.

All these women scrambling about their various lives, united briefly in the act of grooming and a mutual horror of fatness. In Women Plus, I caught them in every possible humiliating posture: rotating soft stomachs to the mirror in frenzied pursuit of their most redeeming angle, pinching ingrown leg hairs to the surface, pawing anti-aging creams and serums. They would dismount the scale to furtively remove hair clips, glasses, and rings, only to step back on to the exact same results. Beauty appeared to be a great, communal project, one that each of us, ignorant to each other’s efforts, toiled at forever; termites whittling away at the same piece of wood.

I spent a lot of time in Women Plus. I happened to love desperation, especially when it wasn’t my own. Also, I found it wonderfully democratic that, immediately following any exercise class, I could see each one of my fellow participants’ pussies. It was as if the exercise class had been a play and we, the actors, now stood in the greenroom, disrobing and assessing our performance. On my fifth day as member, I recognized a pair of truncated limbs emerging from an adjacent shower stall, a familiar manicure and age-mottled chest.

“Zana! I didn’t realize you were a member here!”

It was Mary Alice, a dictatorial accountant at my former employer who always brought her bad Dobermans to the office. But she was dogless now, haphazardly swathed in a short towel.

“Oh, hi Mary Alice!” I said. “I’ve just joined.”

“That’s good, given—”

“It’s good, yes!”

We chatted briefly: all the options, Mary Alice’s own history of membership, the eternally out-of-order sauna, for all the money we paid! I was buffering myself against what I suspected would be Mary Alice’s next question, how I could afford the gym given that I was out of work. I decided to tell her my parents had paid for it. I couldn’t remember if she knew I was one of five born to Bosniak peasants, but I determined the faux admission would be embarrassing enough to deter a follow-up.

But Mary Alice didn’t ask me how I could afford the gym. Instead, she reached beyond me to pinch a cotton swab out from an acetate dispenser. She stuck it straight into her fleshy ear and began to recede into the crowds of anonymous-faced women.

“Well, enjoy it,” she said. “Everybody deserves a bit of luxury in their life, anyways.”

I met the trainer for my complimentary new member session on the lower mezzanine.

“Dino,” he said, extending a hand. His grip was clammy and tentative. He must have been a decade younger than me, brawny with pliable, downwardly sloped features. Dino was also the name of my only American-born brother. I couldn’t tell if this Dino was Bosnian; sometimes Dinos were Croatian or even Italian, so I tried not to get my hopes up.

“Zana,” I replied, awaiting recognition. None came.

He led me into a secret room behind one of the key-padded, frosted doors. Inside were two chairs, facing a singular scale-like machine with winged arms. He instructed me to mount the apparatus and clutch the sensors located at the wing’s end. A touch screen lit up, around which a rainbow wheel twirled and bounced. Eventually, a smooth figure emerged, purple and bald. Under were my height, weight, BMI, and resting heart rate.

“How do you feel about her?” he asked.

“Hmm. She’s charming!” I responded diplomatically.

Unsatisfied, he moved a series of sliders on the screen, raising the amount I worked out per week from one to five, toggling down my weight. Suddenly the purple woman hardened and shrank.

“How do you feel about her now?” he asked.

I told him to keep going. Obligingly, he gauged down the weight until chided by the touchscreen: Underweight BMIs not visualized.

The training session that followed was cursory and brief. I excelled at the triceps extension, which felt both intuitive and adequately challenging, but found myself hopeless on the neighboring leg curl, which required that I assume a vulnerable and unflattering dog-like position. We were in a private cluster of machines with no one nearby. I was crouched on the padded seat, unsure what motion should follow, feeling cluttered.

“I don’t understand,” I said, the desperation in my voice surprising me. Dino bent over and scooped me out of the machine, placing me back on the triceps extension in perfect formation, where I sprang immediately into action. And yet I’d been briefly within his arms: the act so seamless that, by the time I registered I was being moved, I was already on the neighboring machine, exercising. But in that moment, like a kitten lifted by its nape, I’d gone obediently limp.

“Razumijeti me savršeno,” he said. You understand me perfectly. Not a Croat after all.

At the end of the session, Dino walked me through an escalator of exorbitantly priced private training options. I signed up for twice weekly. The money, of course, belonged to another man, Thomas. All of it did.

The summer before college, I worked at a crisis hotline for a teen suicide prevention nonprofit, the idea for which was to pair teens in crisis with other teens. It shared a nondescript, one-level office building with an insurance agency in St. Louis. Of the minimal training I received, most centered around proper operation of the internal software system, where I could sign up for shifts and, if called, complete “SAFE-T,” the Suicide Assessment Five-step Evaluation and Triage, which, more than therapeutic tool, functioned as a cornerstone of liability mitigation.

Hardly anyone ever called. Nearly everyone who did call described themselves as being the victim of incest. Fantastical incest, that was, extravagant incest with complicated plot structures and charismatic one-liners. Invariably, each story would eventually reveal itself to be a fantasy of the caller, who would also eventually reveal himself to be an older man. Thus, it became apparent that the operation wasn’t really a suicide hotline, so much as it was an open channel for adult men to have phone sex with the teens touted as being on the other end of the line. I never forgot the breathy, weightless register of their voices, entering minute seven of recounting sexual violence suffered at the hands of irresistible stepmothers, aunts, and cousins. I would give a thumbs up to my supervisor and rotate my squiggly chair back to face the cubicle wall, following the caller’s instructions completely, including once to shove my fist between my legs and slot myself against my knuckle.

The final call that summer came from Ned. He claimed to be fifteen, but by then I knew better. I began to execute the “SA” in “SAFE-T,” rehearsing the series of required questions to assess the “teen’s” risk level.

“Have you been feeling hopeless lately?”

“Yes.”

“Do you find yourself wishing you could permanently escape from your life?”

“Yes.”

“So, you have thoughts about dying?”

This question caused him to lightly rebuff me. He told me to stop following a script.

“Of course I have thoughts about dying,” he said. “Everyone has thoughts about dying. Don’t you?”

I told him I didn’t think too much about dying. Because my family had fled the war, for us life included dying—featured dying, didn’t think about dying. We’d watched so many people do it, and my life, I told him, had always approximated death. He contested that everyone’s life approximated death, irrespective of ethnocide. Then he described to me what could arguably be placed under the banner of sexual fantasy, but further than that I could not say. It involved a vision of himself being very small, and me, regular-sized, picking him up and placing him around a room. He asked that I move him to the sink’s ledge, to the printer’s tray, to a cabinet filled with cans.

“Could you shut the cabinet door?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“Yes, what?”

“Yes, it’s shut.”

“Can you open the cabinet door and take me out?”

“Yes.”

“Yes, what?”

“Yes, you’re not in the cabinet anymore. Yes, I’m holding you.”

“And could you put me onto the very edge of the arm of the couch?”

I looked around the room to ensure my supervisor wasn’t listening. Then whispered into my headset, “I’m putting you onto the very edge of the arm of the couch.”

“Oh my God, oh my God. I’m going to—”

The phone line clicked; he’d hung up.

Week two. I walked in frenzied loops around the AstroTurf wearing corded earbuds while Thomas masturbated on the other end of the line. He instructed me to clamshell my legs on the pornographic thigh adductor.

“I’m on that machine.”

“Which machine?”

“The one you like. I’m on that machine you like and making eye contact.”

“With who?”

I was actually lying next to the rows of exercise bikes, black curls crushed to a yoga mat, assessing a dry patch near my elbow. I watched a sinewy Orthodox man pedal while a unitarded woman, body bloated by fat transfer cosmetic surgery, assumed a series of stylized poses.

“Everyone,” I told Thomas. “I’m making eye contact with everyone. Men and women.”

I had only met Thomas once, many years prior on my first ever work trip reporting on his LA-based health tech startup. Primarily, I wrote about business, politics, and technology markets in Eastern Europe. I was good at my job, or at least I’d thought. At the end of our drinks, he’d insisted on paying, although I could have expensed it. He pushed my company card back toward me exaggeratedly, “I’ve got it, I’ve got it.” Afterwards, smoking on the street, he asked to see my tits.

For a while, at parties, friends would prompt me to recount the story. I guess they found it funny, how I had obliged: lifting my shirt in a fit of giggles to briefly reveal my breasts, before stamping my cigarette and disappearing into a cab. Thomas had contacted me periodically since, offering beauty treatments and silk slips and money. I politely declined. I made enough as a staff reporter to finance my own life, plus I worried about what he might want in return. And yet I’d stayed in touch, fearing rejection might prompt him to tell my boss about the incident, or liking his attention, I wasn’t sure which.

Sometimes my behavior troubled me. Nonetheless the flash had been a self-protective act, I tried to reassure myself. If my career failed, I could take him up on something. When I was fired, I did.

Daylight savings energized me; like the hyacinths and spring animals and expanses of brown grass I, too, hungered for transformation. For the remainder of March, I met with Dino twice weekly. He even offered additional sessions when we both happened to be at the gym. We both happened to be at the gym a lot. He began to speak to me about his personal life: how it felt to live with his mother at 21, and issues with his girlfriend who was always posting revealing photos of herself on the internet. “Who are they for?” we wondered. Of me, he appeared both curious and skeptical: he was interested in my career as a reporter (had never met one) but confounded by my age (29) and marital status (not).

“Don’t you worry you’re running out of time?” he asked me once as I stroked on the indoor rower. I paused.

“For what?”

He stood above me chewing the inside of his mouth, unsure of what to say.

Once I found his bio on the gym’s website, which reported his training philosophy as “the belief that health and fitness are a multidimensional practice of getting reattuned to what it feels like to live in a human body interacting with a dynamic world.” To live in a human body interacting with a dynamic world, I considered it.

Then I decided to make the transition to living a physical life. I attended a special cycling workshop, involving an elixir shot, blindfolds, an immersive audiovisual installation, and encouragement from the instructor to facilitate a deep connection with the inner landscape of the self. I joined a book club, adult gymnastics, Reformer Pilates, the Tour de France Challenge. I joined the internal family systems group, where I learned that trauma was not only stored in the hips, but also literally written onto your DNA. I imagined God, with His giant, prop-like quill, writing “TRAUMA” again and again on a spiraling double helix in unbroken cursive loops.

I began attending a weekly affirmation workshop led by Tristan, the most important outcome of which, according to him, was to find our own. One week we lay on our backs, doing call-and-responses that Tristan misattributed to a range of ancient texts from the Vedas to the Tao Te Ching. In trancelike repose, we chanted the same affirmation back and forth for seven minutes.

“All my problems have solutions,” Tristan began.

“All my problems have solutions,” the room said back.

“All my problems have solutions.”

“All my problems have solutions.”

“All my problems have solutions.”

A month passed this way.

I spent increasing amounts of time in the broken sauna. Because it was only in that dim cubby of steam-softened hemlock benches that I could find myself reliably alone, and being reliably alone was crucial: I’d begun entertaining a new, roaming gym-based fantasy of Thomas’s, something I preferred not be overheard. It had started standardly, with him fucking me on a series of gym equipment, then become paraphilic and object-based: I was the equipment.

“I don’t get it,” I said to him, “So is it just me, like normal, and you’re pretending I’m the chest press machine? Or is it chimeric, like I’m kind of half-chest press machine, half-woman? Or am I just a machine? And do the other people at the gym know? Is what’s hot about it that I’m pretending to be the chest press machine, but everyone knows I’m a girl?”

On the other end of the line was breath.

“I just want to understand!”

“Where are you now?” he responded in a thin voice.

“I’m in the sauna,” I said angrily.

“You are the sauna.”

“How could I be the sauna? How could you fuck the—”

“You are the sauna, you are the sauna,” he repeated in a register growing higher and breathier. I yanked my earbuds and moved away from them to the opposite bench. I balled up against the wall, closing my eyes. His injunctions upset me, I realized; in fact, I’d been upset for quite a long time. I tried the aerophone breathing exercise from Tristan’s class, but each time I attempted to see my body as the flute’s silver pillar, my imagination collapsed. When I envisioned my body, I just saw my body. I saw my body crumpled up against the wall. In the distance was Thomas’s tin voice, “Are you there? Are you still there?” I am still there, I thought. Here I am. I was seeing a perfectly tautological image of myself where arms were arms and feet were feet. Because people aren’t flutes at all, really. I thought, People are not instruments and they’re also not saunas. People are not even reporters. Or at least I’m not even a reporter. But if I’m not a sauna, flute, or reporter, what am I?

From beyond my tepid hideout, I was interrupted by a panicked shout: “Men!”

I peered through the sauna’s glass door to identify its source: one of the upstairs receptionists, a jittery orthorexic, barreling through Women Plus, waving her twiggy arms about violently. I watched as she opened the steam room door to chastise its wall of vapor: “Men, men, men!”

Once she’d completed her loop, she stood in the marble entryway with her hands funneling her mouth, “Coming to fix the sauna! So please cover yourselves!” From my spot, I watched lazily as the men filed into Women Plus: three technicians in work clothes, looking bedraggled and misplaced against the long spans of tidy ceramic. The receptionist walked alongside them, continuing her chant, “Men, men, men!” The theatrics made them diffident and self-conscious; they shuffled through the throngs of priggish women with their eyes on their work boots, and the women tightened their towels, casting wary glances at the technicians as if any wrong move might result in rape.

Among the technicians was Dino. He, too, looked improper in this setting, sapped of the swagger he assumed on the turf. I hated to see him like that, compunctious. They began to unscrew a panel from the wall outside the sauna, beyond which I could make out a knot of wires. They were focused, unaware that I was just behind the door, and I felt radically uninspired to move. I closed my eyes again and sustained my peaceful image: ears that were ears, lips that were lips. Perhaps I even fell asleep, briefly—the glass door slammed shut and I jolted awake. Dino flared before me, a look of unplaceable horror on his face.

“Why wouldn’t you cover yourself!”

His urgent, wounded tone startled me. I opened my mouth, but in the instant no words formed we both became aware of something—someone—else speaking. A metallic frequency, issuing forth despite its impoundment: a still, small voice querying from the abandoned earbuds, “Are you there? Are you there?”

“What’s going on!” Dino demanded. “Zana, are you okay?”

“I am okay!” I told him forcefully, believing so as I said it. I was no longer dazed; I was righting myself, hoisting my towel over my body and purposefully palming my earbuds. “I’m great, in fact!” I stepped down from the bench, making my way toward the door, then turned back, “You know—” Thomas’s questions spilled forth from my balled fist. “You know, there’s something totally irreducible about me!” I proclaimed. And exited the sauna.

Later, striping lotion down my legs, I overheard a woman murmur: “It’s ultimately just a matter of safety. And it’s like, I’m sure there are plenty of women and femme sauna technicians who could have used a job.”

I came down with a fever; it must have been the weather, I suppose. For a while after the sauna incident I was at my apartment, cooking nice meals and reading by damp windows. I spent three days making a soup. I worked in intervals—chopping leeks, soaking navy beans. While my soup simmered, I took baths and rubbed camphor ointment on my chest and palms. I didn’t talk to Thomas at all. As a little girl I had played nurse with my stuffed animals and a pink toy stethoscope, pushing it to the plush bodies of bunnies and bears, ears filled with the nothing sound of cotton. Around ten I discovered the toy really worked; after that I would lie on the polyester carpet of our living room, the stethoscope’s cool metal drum compressed to my chest, listening to rounds of my own heartbeat. Curing myself of the fever recalled that reflexive role, caregiver and cared for: I was still that little girl star-fished in the living room. I was still the audience to my own heart.

The rain broke, then my fever. I went on many identical walks. I traveled southward along Fenimore toward the grassy lots of the partially defunct hospital, one day venturing down into the green-gated Catholic cemetery just beyond the complex’s grounds. I thought of my baba Marija, a Bosnian Croat, who’d converted from Catholicism to marry my deda, a Sunni. It was an unlikely love marriage that, growing up, my mother often invoked as threat. She was a woman of frequent citation so, in our household, an unscraped dish or disobeyed curfew could conjure: “Your baba didn’t give up Jesus for you to…” But my baba didn’t give up Jesus, or at least not really. She’d retained private allegiance to her maiden faith, and—after my deda was killed in a market shelling in 1993 and our family, including my pregnant mother, fled Sarajevo, and after my Dino was born, miraculously, in St. Louis—she began to attend church again. Toward the end of her life, I would escort her. Outside the church, with its neat red exterior and boxes of marigolds, dressed in her fanciest headscarf, my baba always looked terribly asynchronous and little. She was a relic of a different country, an old world, a fallen empire. In the Holy Cross cemetery where I walked, there were no Marijas, only Marys.

On the way back I traveled on the bluing main road, entering stores and exiting them, collecting soy candlesticks or glitter nail polish or fruit juice. Once home, I ate a portion of soup and fell asleep with all the windows open and candlesticks burning down. Spring expanded the evenings, but I didn’t need them; I slept early then, early and often.

Intrepidly, I returned to the gym. Three weeks had passed since the sauna incident. The orthorexic woman sat behind the desk, tearing corners off registration papers. Dino was across the lobby, waiting at the cafe in midnight-colored compression clothes. I opened the app and flashed my code to the outstretched scanner. The orthorexic woman flipped the scanner up and down; when there was no affirmative beep, she examined the glass reader, then the cord. I offered to close and reopen the app, but that didn’t work either.

“What’s the last name?”

“Hadžić.”

“It’s not in the system.”

I had never felt more separated from the gym than I did forced to stand in its entryway explaining keystrokes for diacritics. I watched Dino cross toward the stairwell, newly procured banana shake in hand. He stopped to watch, inquisitively. I shrugged at him, wondering if he might rescue me.

The orthorexic woman told me that my account was suspended: no one had paid my membership fee for April. Or the last month of private training sessions, of which there had been sixteen. I thought about all the informal sessions with Dino, the ones that had seemed free. He stood there, some twenty feet off, too far away to hear.

“What about the card on file?”

I watched Dino turn, descending back into the gym, a place I realized then I’d never return to.

“It declined. Your outstanding balance is $2,800. Do you want to try a different card?”

We looked at each other suspiciously. I told her I left my wallet at home and would call in my card later.

Outside, spring was in full swing, enchanting and rank. I remembered an April drive back from church with baba, it must have been over a decade earlier. Often she’d recount lessons from her study group on the ride home—this one had been on introductions. She’d learned that the traditional English translation of the name God uses to introduce Himself to Moses at the burning bush, I Am That I Am, did not account for an idiosyncratic modal form of the Biblical Hebrew, wherein the verb “to be” can mean “I am” and “I will be” at once. I filled in much about the grammar years later. In the car, she’d only said, “the English is wrong.” The proper translation, according to her, was, “I will be what I am becoming.”

I will be what I am becoming, I thought. It was an affirmation I liked.

That fall, I passed the gym by accident on my way to a second date. It thrummed with the bright light of a soundless fire alarm. Throngs of people hung around the sidewalk, calmly conversing with each other. On the street, illuminated by dusk, they looked rather garish: sinewy bodies, slick with sweat, faces swollen with injectables. Against the imperious downtown high rises, the technology of their workout sets appeared nearly modest. I had almost forgotten about my six weeks at the gym since beginning a new reporting job. With my salary, I’d prudently joined Crunch, a far inferior institution that I could afford all on my own.

The blinking eventually subsided. For a moment, I strained my neck from across the street to watch the patrons file back inside. I took note of their gait and affect, people who had once occupied the background of my life, receding into memory one by one. I figured the fire alarm must have somehow been triggered by accident. There was no emergency. Either that, or the emergency had passed.