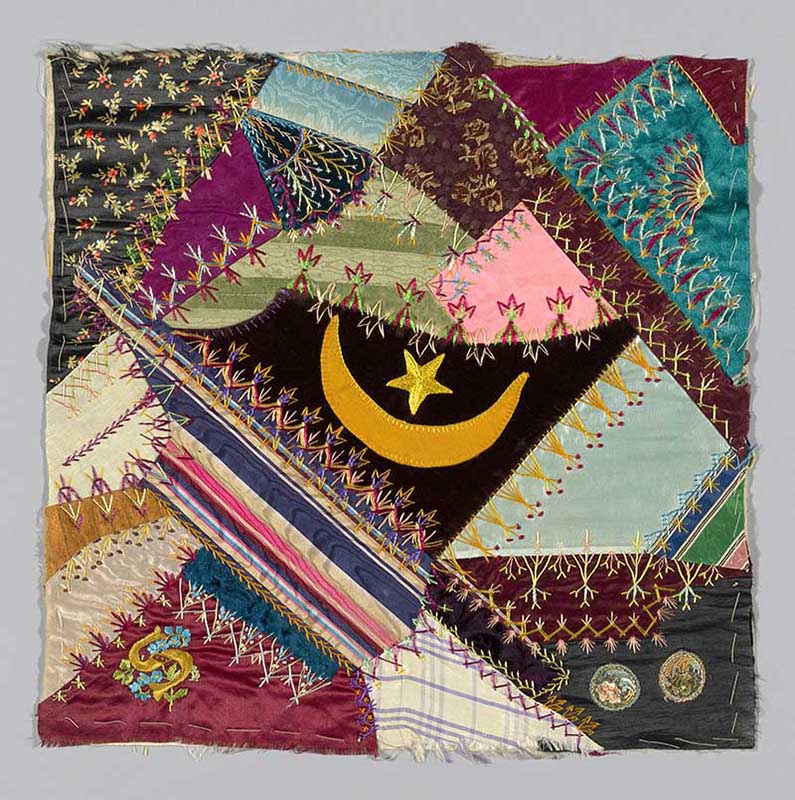

Square from a “Crazy Quilt,” c. 1884. The Art Institute of Chicago.

THE WAVES

The sky flashes and the great sea. The wind rises and the great sea and there is no way to undo it. It swells and lashes. I clutched the rail at the side of the bed and stared at the wall. Drift is a sea word. Adjust for drift. Start turning your boat now. I sat in the boat and the sky cracked open. It might as well have. I sat in the boat and yelled at the waves. I might as well have. I strung the words and everything under the shattered clouds in sentences. By which I mean, which is to say, the wine-dark sea. It bruises where the oars strike. Hitched step, stitched thought. What it is and where it wants to go. Someone needs to knot the rope. Someone needs to finish it, a single thought completely. That it could follow. That there could be a rosy-fingered, wine-dark sea consequently breaking. I am the mermaids singing, twisted in the sheets. I am, I have, I know and say. I know, I have, I will and do. Whitecaps and froth. I yelled at the waves. The ghost of myself slept deep. Try to finish, finish the thought. Do not drop anchor here. That it could follow, that there could be a word and then another. I recalibrated and the light streaming completely down in shifts. Pull yourself out. I clutched the rail at the side of the bed all night, the light stuttering against the waves. What trips over terms in the names dragged up and knocking things over with the names of other things between the swells. The fingered dawn. The terrible shore. The complicated mooring.

MIND CONTROL

The doctor ran a pen down the sole of my foot. Nothing happened. I was optimistic but no one was smiling. I used the mind-control techniques I learned from the cult but I still couldn’t wiggle my toes. The doctor put the pen back in his pocket. The gloom before the sun goes down is called the gloaming. I massaged my leg in the gloaming. The lotion was cold and smelled like lavender. It was strange to feel my leg from the outside only. I tried to visualize, I tried to imagine my leg from the inside. I lay on my back and found my edges, like they teach you in the psychic self-defense pamphlets, and I filled myself with a thick, gold light. It didn’t work. My dream body was missing a leg as well. I floated to the ceiling and looked down at myself. No leg. I was a psychic for a long time before I started taking meds. I saw through things. After meds, I realized I was just another empath in a Denny’s, sinking onion rings in ranch dressing in the middle of the night. A body of light is made of photons. It has no mass. It’s easy enough to float to the ceiling if you want to. You can teleport to Illinois or travel, house to house, and watch over your friends as they sleep. I did it a lot, for a while. I spent my nights watching over my friends but then I was too tired during the day to hang out with them. I still fly around at night sometimes. I lie on the grass, face down, and turn off the gravity. Change the context and then it’s just a matter of falling backwards. Some people like to do handstands and push themselves away, so they can fall into the sky feet first. The local body is a lie, like they said in the cult. We hover over the surface, like they said. And it all makes sense until something buckles.

FAMILY THERAPY

The morning after my father killed his first wife, he woke up next to her dead body, rose from their bed, and began his morning routine. At lunch, from his office, he called the landlord and asked him to check on her. He was worried, he said. The night before, he had taken her pill bottles and lined them up on the bathroom counter. He said unkind things, using words like burden and ruin. He stood in the doorway and wouldn’t let her pass until the bottles were empty. They went to bed, he said goodnight, she said goodbye, they turned their backs to each other under the thick blankets. This is what he said, my father, in family therapy, a few months before he died. I had already figured it out, mostly. The other son had always been more tender, gullible. And it was his mother, not mine, so you can see how it would be easier for me to get my head around it. They watched each other, trying to figure who was getting their head around it. The therapist watched my father. My father watched the other son. The other son turned away and looked out the window, where the wind was pushing some leaves around. I confess, I feel bad for the landlord. He must have known. The body had been dead all night. I imagine him with his heavy ring of keys, unlocking all the doors to all the rooms he’s been responsible for, year after year, until he’s no longer surprised by the residue: empty bottles in a mirrored cabinet, a wedding ring at the edge of a sink.

ROOM TONE

They drove west on the river road and then turned north. The evening was pleasant and they had the windows down. It had recently rained. The desert was blooming. The palo verde trees were yellow with pollen. He pulled up to the house and turned off the radio. He adjusted his suit coat. Her high heels sank a little in the gravel driveway. He held her hand. She held a bottle of white wine. The brick path rose several steps and then ran along the side of the house, next to a long stretch of fresh cut grass. The light in one of the second-story bedrooms was on. They rang the bell and my stepmother met them at the door and led them down the hallway, past the stairs, to the living room. The light over the stairs was on. The light at the top of the stairs was on. The chiropractor raised his glass and made a toast. My father made a joke and everyone laughed. There was a cheese plate with olives and almonds and figs. They had drinks and talked about their sons. There was jazz playing in the background. The house was soft and plush. The chiropractor and his wife were glad to talk about their sons, though they were also very glad to be away from them for the night. My father and the chiropractor spoke of legacy and disappointments, and how much children cost. The women asked each other questions: How are they? Are they healthy? Are they getting along? The chiropractor’s wife had two little ones. My stepmother had two big ones. And me. —And how is Richard doing? —He’s fine. He’s upstairs, doing homework. And that was it. They moved to the dining room. Through the sliding glass doors they could see the clean, flat water of the illuminated swimming pool, the cactus and palm trees lit by tiny spotlights. They had fish with dill sauce, scalloped potatoes, a tossed green salad. It was an ordinary dinner party, which was impressive since my father was sleeping with the chiropractor’s wife. It must have been odd that I didn’t come downstairs to say hello or goodbye to them when they left. I wasn’t there. I didn’t live there anymore. They didn’t want me there. It was awkward, so they didn’t tell anybody. My stepmother waited until she was sure that they were down the road before she climbed the stairs. Light was coming through the gap between my bedroom door and the carpet. And there was a silence, an active silence, a restless omission. A silence different than the silence of the hall. My stepmother opened the door just enough to reach the light switch. She turned off the light and shut the door.

FICTION

I bet on red. I took it for a spin. I jawboned a tall tale and got penned in with the liars. I played the goat and kicked from shank of night ’til moonsink. It was mesmerizing. I told them about the river, how the canoe struck rock and the birch bark cracked. Boot by boot we shoveled water but our feet went cold and the boat sank. It wasn’t true. From the cabinet came a banging. From the cabinet a banging came. Something is banging on the cabinet, from the inside. Invisible banging. Things happen—the characters deploy, performing actions. You have to throw a body out of the van, otherwise it’s just philosophy. He had the smoothest chalk. If it was chalk. They all stocked up. She rolled up the rug but his feet stuck out. It was embarrassing. The children climbed the bleachers, selling snow cones under the giant tent striped red and cream, wearing their fake mustaches. And that’s not the worst of it. Ghosts. And bears, every night. 800, 900—the woods were full of them. The yeast in the loaf, the horse in the glue, the thickening blue-white day. Squinting into the brilliant light of it and getting tense. Galvanized by it. You stay up late, you sharpen pencils. You learn to predict the future by building hypotheticals—the little creep, in the weeds behind the gas station; the detectives dragging the lake with chandeliers. Dear John, I am right up in it. Attacked by bears again and this is only half of it—the moments starting to stick. Proof of concept. The shadow of something that hasn’t happened yet, potentially consequential. Meet me at the bus stop, I won’t have long. The story reminds you of something and the city goes incandescent. What’s the truth? No sense in asking. Leaves fall from an invisible tree and the rope pulls taut. It’s nothing short of staggering. I put a saddle on it and rode it into the ground. It made them sad. The horse wasn’t actually real until I killed it.

NONFICTION

Tell me your life story, now I’m bored. I want to eat some pinto beans but I have eaten all the pinto beans. I want to play with the dog. Death star, crab puff, blowhole. I’m still not saying it right. The vines climbed up the walls of the house and we never really noticed. The legs of the bed frame scratched the floor. We never really noticed. Porterhouse, swimming pool. Lower your expectations. If the image doesn’t have a point, it’s just an autopsy—undigested biography. The hint of a smile and dead eyes. I remember versus that reminds me. One continues, one connects. Facts: The shower curtain had yellow sunbursts on it, the soap was green. I, wrongly, shoved potato peels deep into the garbage disposal. I thought it could handle it. The shattered bottle of balsamic vinegar? My fault as well. It stained the wall. I am not lying. These are not metaphors. The confectioner takes almond paste and crafts tiny, detailed replicas of fruits and pigs that taste like almond paste. They look interesting. They are not interesting. Almond paste pretending to be everything but almonds. They are garbage cans. You’re eating garbage cans. Say it plain, see if it’s powerful. Say it slant, see if it’s possible. Distraction, diversion, the clumsy decorations? Cheap magic, a smoke screen. Without the truth, there can be no fiction. Nonsense needs reason. To push against. I didn’t howl at the moon, I yelled at a lamp. Subject verb. Someone wept. Some things are more important than poetry.

CLOUD FACTORY

Zebras have stripes, leopards have parties. Bobcats eat ham sandwiches and crème brûlée. A bird will sit on your finger and tell you a story. A dog will sleep at your feet all night and not overthink it. The dog is chasing squirrels in the backyard of a dream. I was a beautiful day, I was yellow next to pink. I was a brush fire, a telephone. I was, I am. The mayor gave me a sash and a gift certificate for a complimentary dinner. He was very proud. It was a cakewalk. I took the long road to thicken the gravy. I pushed the words around. I pushed them hard. I did it blind, with the pictures in my head, and the technicians in the cloud factory filled the sky: cumulous, cirrus, cumulonimbus. They made some shapes so we could guess. We looked at them. I did. Meaning comes from somewhere. You could feel the figs swelling in the fig trees all afternoon. Imagination—image is the coal that fuels its little engines. Shovel coal. Call it love, call it a day’s work. Keep the furnace burning in the factory. The puff puff puff of possibility. You don’t need to know someone to be their lover, you don’t need to know anything. To get over Ben, I thought about Steve. To get over Steve, I thought about Paul. I went swimming in a blue rectangle. It wasn’t actually swimming but I called it swimming. Around the pool: A thousand grasshoppers. Strawberry cake: If only I had the room. The planes land and sometimes there is luggage, so here’s a little lamb for you. Maybe it’s a cow. And a tree in the background and a bat in the tree like a blot or a stain or a gathering storm. I know, I’m doing it wrong—meow, meow, meow. Big words and pig fat, très estupido—but then, what do you know, the invisible table reappears. Go ahead and finish the thought. Say the dream was real and the wall imaginary. Fill the sky with clouds. A thought came up to the window and surprised me. And that was that. Nothing but fingerprints on glass. Don’t blame me. I didn’t invent the world, I’m just looking at it.

WORD PROBLEMS

A fox, a chicken, and a bag of grain wait patiently by the side of a river. If left alone, the chicken will eat the grain. If left alone, the fox will eat the chicken. You can only fit one in your boat at a time. How will you get everything across the river? You and your friend are leaving Alamogordo in opposite directions. It makes you sad. Regret is a version of yearning. What were you doing in Alamogordo? A man is driving down a backcountry road. He is thinking about building a machine. The machine will be black and yellow and it will destroy the world. By the side of the road a bear, a ghost, and a robot watch him drive by. The man does not see them because he is preoccupied with his thoughts. The ghost eats mayonnaise. He is unhappy because he is dead. The robot is also not alive, but not alive in a different way. The robot is an empty box. He feels nothing. The ghost is a feeling without a body. The man is a heart in a trashcan. The bear is just a bear. He is drinking diet soda and throwing snowballs at a log cabin. The cabin’s on fire. So much is wrong, so terribly wrong. A man is driving down a backcountry road. He might as well be. The machine will destroy the world with joy. It won’t solve anything. He is leaving Alamogordo, trying to get somewhere. The robot has a body and can tell him how to get there. The ghost, instead, can only tell him where it is. Put the chicken in the boat and take it to the other side. Go back for the bag of grain. Put the bag of grain in the boat and take it to the other side. Leave it. Take the chicken back in the boat with you, so you can keep an eye on it. The trick is to keep your eye on the chicken. Attention, friends. Where are you putting your attention? You can’t take everything with you. I am trying to tell you this the right way, from the right place in the story: a man in a car looking out every window, unobstructed views in all directions. Some people think they’ll find the answer in Alamogordo but others believe the answer lies fifty-three hundred miles away, hidden in a mysterious cave in France. But let us leave the question suspended for a moment and enter a secret room behind the laundromat. What is the real problem? So much is so terribly, terribly wrong. There’s a fire. Set down the chicken and pick up the fox and drop off the fox and go get the chicken. It’s exhausting, keeping your eye on the chicken. There’s a fire, there’s a fire. Leave the chicken, leave Alamogordo. Where is your friend? Why are you sad? Let it rain, let it pour. Hallelujah.

PHOTO BOOTH

The photo booth was a small box with a red curtain. It took four photographs and printed them on a strip. The restaurant had four rooms: storage, kitchen, dining, lounge. The photo booth was in the lounge, where we would eventually put the bar. I worked the fourth shift, dinner and the bar rush, and after work I would feed my tips into the machine and sit in the small box. I took pictures of myself until I got tired of myself. It didn’t take long. I started dressing up, pretending to be other people. I used props. The curtain was a half curtain. I would pull it shut to obscure my head and shoulders but you could see my legs. What was being photographed was hidden but everything outside the frame was visible. If you watched me, everything was reversed: the framed space inaccessible, the space outside the frame illuminated. The strip would document what happened in the box but by the time the strip was ready, it was over. I tried to build a narrative on the strips, but the time I had between the photos was brief. Everything had to be done quickly. It was interesting: the gap in time between the shots, between the strips—the missing moments. You couldn’t capture everything. I started leaving the curtain open so people could hand me props but sometimes a hand would end up in a shot and break the artifice, alluding to a larger world. One of the line cooks was also manipulating the machine. I was making little stories but he was documenting something else. A waiter spends his nights delivering the goods—milkshakes, omlets, chicken-fried steak—and returning with a tray of residue. A line cook holds his ground and cooks. He would watch me through the pass-through window, running around. I would watch him through the pass-through window, standing still. From the booth, with the curtain open, you could see into the dining room—customers at tables or navigating past the waiters and their oval trays. The line cook realized that inside the booth, with a mirror at an angle, he could take pictures of the dining room. He had moved outside the box, past portraiture. With a second person holding a second mirror, reflecting back at him, he could take pictures of himself in the booth, holding the first mirror. With two people and two mirrors, he could make the photo booth take pictures of itself, flashing through the minutes.

Richard Siken is a poet and painter. His book Crush won the 2004 Yale Series of Younger Poets prize, selected by Louise Glück, a Lambda Literary Award, a Thom Gunn Award, and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. His other books are War of the Foxes (Copper Canyon Press, 2015) and the 2025 National Book Award finalist I Do Know Some Things (forthcoming, Copper Canyon Press, 2025). Siken is a recipient of fellowships from the Lannan Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. He lives in Tucson, Arizona.

(view contributions by Richard Siken)