I heard about the killing from a neighbor. She said everyone was doing it; she said we had to do it; she said it was good and right to do it. She pointed to one of the pretty brown moths on the pavement, said its name, and stomped.

The plan was to extinguish the species by hand. The plan was stupid, it would never work, but I joined in the stomping and smacking. It was a simple rule, easy to follow, a sanctioned act of minor violence. I liked knowing that I was doing good for the environment. The moths, so the neighbor said, surprised that I didn’t already know, were an invasive species. Someone had brought them from far away, probably by accident. Now, within just a few months, the moths were eating everything in their sight, nibbling leaves, destroying gardens and crops, swarming and spreading.

The neighbor was right. The moths were everywhere, once you knew to look. They multiplied far faster than our hands could swat. Sometimes I thought I saw one that looked different from the original arrivals. Larger, for instance, or better camouflaged against the sidewalk, as if they were evolving on their own timeline.

One night I came home to find hundreds of them, brown-spotted wings glinting as they gently flexed and relaxed, settling like ivy all over the front door of the building. I envisioned myself leaning into the plexiglass with arms outstretched and smothering the lot of them with my body, coating my clothing in the brittle gray dust that they left behind when they died. A deadly embrace. But I couldn’t bring myself to mass murder, even if I knew that it was the right thing to do.

The moths descended during the long middle of a hot autumn. My room was poorly ventilated and my mattress and pillow were permanently soiled with sweat. It didn’t matter that I had no blanket, since it was so hot, but I didn’t even have sheets or a pillow case, which I knew was disgusting. It would have driven my mother crazy if she’d known. Things like clean pillow cases, a nice pair of underwear, a good leather belt—she insisted these were necessary to spend money on. But so many things were necessary, and I didn’t know where or whether to start constructing a life. I had accepted that I no longer lived in a household. That’s not what it was, that rooming house with four other guys.

Unlike the moths, I was isolated—and slow. My emotion as I set out each morning looking for work was a kind of loneliness so extreme it had gone stale. I didn’t even bother to feel it; the feeling bored me. Boredom is bred by stasis. Time went in a loop; the feeling felt permanent. Every morning I showed up at the corner behind the hardware store to wait alongside a row of other guys on the sidewalk, where we’d trade news and jokes and snacks but mostly stand in silence, all of us waiting for someone to slow down a car and lower a window and ask us to hop in and travel to their homes or constructions sites and lend them our hands and arms and torsos and legs and feet.

I had been standing on the sidewalk for six months and had worked twelve jobs so far. Some of the guys had been doing this for years. On certain grim days I thought that we had been standing there since time immemorial… that we would turn into statues or monuments. But no. This situation, as my mother would have told me, was a blip in time. Humanity in general is a blip in time. The violence of this moment is a blip in a blip.

The guys lined up in order of appearance, so arriving early was most of the game. Rarely was I first; I had a hard time hauling myself out of bed. My motivation was money, of course, money to send to my sister, but this goal became fuzzy in the morning, abstract. The heat, my heavy dreams. Money? No, I wanted sleep.

On the first of September I woke without an alarm just after dawn. I sat up with a gasp, prickling with sweat. I couldn’t remember what I’d been dreaming about.

In the indentation where my head had been on the dirty pillow was a moth. Same as all the others. Twitching. I slapped my hand down without thinking, then flipped my pillow over to hide the mess. I got dressed for work.

I was second in line on the sidewalk that morning, behind one of my housemates, the early riser. “Someone decided to work today!” He handed me a chunk of the sweet cake he was eating from a foil wrapper. After some time had passed I asked him why nobody else had shown up yet. “Man. You didn’t see?”

My phone had broken a week before and I had no cash to fix it. I should have noticed the quiet streets on my walk to work. A patrol was out that day, he said. Better to stay inside.

“What are you doing out here then?”

He sighed, smiled, ate his last bite of cake. “Why do you think.” Pointed to his pocket.

At 8am a brown truck slowed down and stopped by the two of us. The guy inside the car told him that he needed someone to paint his barn: Easy. Painting jobs were the best.

Some days no cars stopped at all. I don’t know whether everyone driving by knew why we were standing there expectantly. They were just hardware store shoppers; they didn’t speak the language of cheap day labor; they took their linoleum tiles and their ceiling fans home and tried to follow YouTube instructions, and when they failed to DIY they gave up and found a reputable company to come and do the work for ten times what one of us would charge.

If I got very lucky, maybe one day a construction company would hire me. My pay would stay the same, the company taking the other nine-tenths, but it would be reliable work. I would be able to tell my sister how much to expect every month. Funeral expenses had completely exhausted our supply and we were starting from scratch again. The pot would fill up faster now that there were only two of us.

At noon, a silver sedan pulled up so tightly to the curb that the tire squeaked. The passenger window rolled down in slow motion. As always, the scroll made me nervous: the imbalance between the person protected inside the car and the person exposed outside. I bent down and peered in.

The guy was about my age, maybe younger. He was wearing a blue baseball cap that said Believe. He squinted at me and cocked his head. “Hey buddy,” he said. “I’ve got a leaky roof.”

I thrust my head across the threshold of the window, just a little way into the car, and told him my rate.

“Cool,” he said, and patted the seat. I got in.

We exchanged names and then drove in silence. He probably assumed I couldn’t speak the language well enough to have a conversation. This worked in my favor. I didn’t have any experience fixing roofs. I had learned how to do a lot of things by then by watching videos and asking the other guys for advice. I figured I could improvise.

The air conditioning in the car was blasting and my sweat froze to my body. I shivered. A moth splattered on the windshield, then another. “Little bastards,” said the man, shaking his head. He flexed his fingers to squeeze liquid from the glands of his car onto the windshield and then flicked on the wipers. A gray smear remained.

The house was a one-and-a-half-story ranch, with beige plastic siding and white plastic window frames. The whole thing looked like it was molded out of one piece of plastic. Like a giant toy house. This wasn’t quality construction. I’d worked on enough nice houses to know the difference. The house was on a small lot, edged in by similar houses on either side, and its paltry patch of lawn was brown in parts. Still, the grass had been recently mown.

The man parked the car behind a red van in the driveway and slapped his hands on the steering wheel to indicate that we had arrived.

Outside, he popped the trunk to show me several vacuum-sealed packages of brown-gray shingles and some packets of nails. I was relieved. It looked straightforward enough. Nail shingle to roof, repeat.

As I readjusted a package of shingles over my shoulder so I could begin climbing the ladder after him, I noticed that a rain gutter had become detached from the bracket meant to hold it to the side of the house. Water was dripping from it sideways.

I called up to the man. “Want me to fix the gutter?”

He looked down at me from his position midway up the ladder. “No point,” he said. “ It’ll just fall off again.”

I clumsily hauled myself onto the edge of the roof, which was pitched at a steep angle up to a ridge, like a folded piece of paper. I don’t mind heights, but I do mind angles. Leaning into or away from an incline is how you ruin your knees, your neck.

“So, yeah, I guess you can see the problem,” the man said, once we were both on the roof, leaning our bodies so sharply forward that we were almost kneeling. His face was cast in shadow by the brim of his hat.

We looked at the roof ahead and above us. I almost laughed. Sure, I could see the problem.

A large rectangular section in the middle of this side of the roof was gone. We were looking at a hole the size of a large window or a small doorway. The shingles were missing, yes, but whatever had mauled the roof had also ripped away all the other important material beneath the shingles and left a gaping hole. If the house were knocked on its side, the hole would be an easy entrance. Add some stairs and just step inside.

Around the edges of the hole, torn pieces of thick plastic fluttered and wisps of pink insulation puffed out. Just inside the hole, two wooden beams ran lengthwise. These beams constituted the armature of the structure we were standing on. Seeing the skeleton of the house unnerved me. Beneath the hole, darkness loomed. I couldn’t see what was down there, despite the sun shining down on us. I spent a long minute staring into the nothingness, zoning out, my pupils expanding to no avail. Time slowed; gravity took effect; I swayed forward—I caught myself.

I wanted to ask what had caused the roof to fail like this, but worried that it would be rude. Maybe the roof was so cheap and crappy that it had just given way. Maybe something awful had happened inside the house and, disgusted, the roof had absconded with itself.

Maybe it was supposed to be obvious what had happened. Had there been a storm recently? I was sure I’d have remembered rain. So long without rain.

The Believe man put his hands on his hips in an unconvincingly workman-like way. “Then let’s get those shingles on.” He bent and rifled through a toolbox wedged next to the gutter.

Covering this hole with shingles would be like plastering post-its over a gaping wound. “You’re the boss,” I said, and dragged a package of shingles and a box of nails as I scrabbled up to the ridge of the roof, up past the hole.

Naturally I looked into the hole as I climbed; I thought I could see a glimmer of light shining up from below, but perhaps it was just sunlight reflecting off of a piece of metal sticking out from a beam. There must be hundreds of metal screws and nails and brackets strewn about this mess. Better be careful. The guy was wearing work gloves, but he hadn’t given me any. Another thing I should have bought for myself. More important than a pillowcase, surely.

The man knelt at the bottom. I arranged myself at the top, crouching just below the ridge of the roof, trying not to tip forward. I had to hunch my back in a drastic way to keep my balance. Hovering directly above the hole, I stared into the void. Nothing. No depth of field.

A whistle—I looked up just in time to snatch the hammer the guy threw me across the hole.

He picked up a nail gun and started to shoot through the shingles, attaching them to one of the exposed beams running across the bottom of the hole. No insulation, sheathing, plywood, tar—I didn’t need to know the details to know we were skipping days of work. Wait until I tell the guys about this later, I thought. Jesus Christ.

As there was only one nail gun, I picked up a hammer. I started to work I copied his method, working my way across the other beam from above, slowly beating the tiny nails through the flimsy, roughly textured shingles into the wood.

The guy spoke a bit while we worked. I made affirmative noises, but didn’t speak too much. I can’t disguise my fluency if I talk.

He told me about his girlfriend, who he said was in the house beneath us at that very moment, working downstairs in her “home office.” She answered a customer service hotline, he said, for a software company. “She’s hella smart,” he explained proudly, pressing the tip of the nail gun into the pebbly surface of a shingle and pausing before squeezing the trigger.

Downstairs. That must mean somewhere below us, below the void. How far down did the nothing go?

“This is her house, you know.” He awkwardly readjusted his position to keep himself propped up. I brought the hammer down hard and the nail I struck bent and skidded off the surface of the shingle and skittered down into the wide nothing. I waited to hear the nail hit something but no sound came from the drop.

“I mean, I live here too, now,” he went on, “but she bought it. The least I can do is like, keep it fixed up, or, like, help out where I can.”

Sun passed out from the cloud cover and we were bathed in bright light for a few moments. Then we were again cast in shadow. The shifts in light did nothing to illuminate the space below the hole.

I couldn’t hear what he said next, except the words “time” and “expecting.” He glanced up at me from under the rim of his cap, waiting for my reaction.

Expecting what? Up here? A surge of panic. Was someone coming? I listened for a car. I couldn’t see the road. If a patrol showed up right now, I’d never make it down the ladder in time. I realized I was in a vulnerable position.

Registering my confusion, he made a swinging motion with his arms, still holding the nail gun in one hand.

Expecting a baby. Of course. He was talking about himself and his girlfriend, not the two of us. He’d thought I didn’t understand the words. “Wow,” I said. “Congratulations.” I placed a nail with precision; I brought down the hammer.

It took twenty minutes for me to reach the end of the beam, working slowly, tacking shingles onto the wood, and I straightened up when I got there, stretching out my back. I obviously had nowhere to go now. We were icing a cake that had collapsed. I considered asking for a glass of water to buy some time.

He had reached the end of his beam too. Incredulously, I watched him hold up a shingle in the air, contemplate what to do with it, and then pick up another shingle. He took them together in one hand and shot the nail gun through to hold them together. He admired his handiwork and reached for a third.

He was going to try to connect shingles in a long row, like a string of gingerbread men made out of construction paper in a kindergarten classroom.

Watching him fumble around, missing his mark repeatedly with the nail gun, I felt sorry for the guy. He didn’t know what he was doing, and he could lose a finger doing it. I didn’t know whether I should help uphold his fantasy, or undermine it by suggesting we watch a YouTube instructional. I didn’t want him to blame me when it inevitably fell apart. On the other hand, I sensed that he had recruited me to prop up his delusion of competency. To make him feel like the boss. To make this look like a roof, even if only until the next strong wind.

Being smarter isn’t always smart, I could hear my mother say. Very well. I would help assemble strings of shingles over a hole.

To my left, I saw a movement. I turned to look and nothing was there. My eyes must have deceived me. Then something moved once more. I bent down to look closer. Against the pebbly gray-brown of the shingles, a moth tensed its wings.

It wasn’t the same color I was familiar with, and it was larger than the others I’d seen, but it was the same species. The same wing shape—like two lobes of a maple leaf. But speckled, like the shingles. Strange, how well it camouflaged against the roof.

When all the wrong animals were going extinct all the time, we were supposed to make this animal go extinct on purpose. For a higher purpose. A greater good. A goal bigger than any one of us could ever accomplish by ourselves. It was beautiful, from that perspective.

Clenching my fingers into a fist, I brought my hand down on the moth. When I raised my hand again, I felt pain right away.

I must have hit the surface too hard, I thought—but no, no, it was a different sort of pain, localized and specific and shocking. When I inspected my skin I saw a brutal red spot with jagged lines of inflammation already extending from the center. A sting. I’d been stung.

The insect was dead. I blew on its carcass, afraid to touch it again. The wings, which so quickly turned to particulate matter, fluttered open and a few pieces blew away. Poking up from the body was a thin orange point, like the pistil of a dangerous flower. Sharp as a needle at the end.

The sun escaped a bank of clouds again; my neck prickled and ran with sweat. “Oh,” I said, without meaning to, and sat down on my butt.

The Believe guy called up to me and I mumbled, “Just a minute,” but then I felt like I might need more than a minute. The sun wasn’t the reason for the heat spreading through my body, nor the wetness I felt clouding my eyes. The heel of my hand pulsed with an intense and furious pain.

I hadn’t heard anything about the insects being dangerous. I must have hit the wrong bug, I thought, killed something endangered and precious instead of something excessive and wicked.

I’d made a grave mistake. I was swaying forward. The man was scrabbling up the roof to try to reach me.

Only halfway aware of what was happening, I certainly couldn’t do anything to stop it. My body had gone completely slack and wasn’t responding to instructions. I pitched forward.

“Hey hey!” I heard. My cheek hit a crossbeam. The horizon tilted. I fell, rolled, my shoulder hit a crossbeam.

“Hey!” Hands scrabbled at my shoulder, yanking my shirt from its tidy tuck and pulling it up to my armpits. But this only served to rotate me until I was horizontal against the roof, which is to say, I was positioned exactly between beams. My legs slipped through the gap, and in a matter of seconds, the rest of me followed.

Small pieces of drywall around the edges of the hole gave way, ripping and cracking with a sound like the crash you hear underwater when someone else jumps in.

“What the FUCK!” I heard as I fell.

I was an embryo. I was a softshell crab. I was a wet and reluctant animal. My mother told me that I’d spent nearly ten months in the womb. I was born, eventually, but my reluctance to enter the world stayed buried inside me, and over time it multiplied into many forms of reluctance, a crowd of reluctances huddled around my organs.

As a child, I was reluctant to leave my mother’s side. I was reluctant to leave my sister’s side, too. I was reluctant to raise my eyes. I was reluctant to get dressed in the morning. But the greatest of my reluctances was my reluctance to speak. I didn’t know the language when we arrived in this town, and it took me several years to admit to myself and my teachers and classmates that I understood everything perfectly. I could do the homework, read the books. I was born again, into language, and I didn’t like the responsibility.

I was the only one who managed to learn to speak and read so well. My sister always told me she was too old by the time we got here. My mother, she was too busy. So busy, the busiest. She was still planting gardens until the day she died. At least that’s what my sister told me over the phone. I hadn’t seen either of them in four years. I wouldn’t see my mother again.

I woke up unsure of where I was. My left arm was numb, as if I had slept in an awkward position and crushed it in the night. My eyes fluttered open and then closed against the brightness—I wasn’t used to waking up with the sun in my face.

I was looking up at a gash in the ceiling, above which the sky was impossibly white.

I was, apparently, in a bed. My head was, apparently, on a pillow.

At the foot of the bed was a man I didn’t recognize. Beside him was a small and unattractive woman with an enormous belly.

They stood outside the patch of illumination, in near total darkness. It was as if I was spotlit on stage and they were standing off in the wings.

Naturally, I was disoriented. I tried to heave myself up, but my left arm wasn’t cooperating. The plush comforter cover beneath me was covered in what looked like sand or sediment and chalky white chunks. My boots, also dusted in white particles, had left a brown smear on the baby blue fabric. I shouldn’t be wearing work boots in bed! I swung one leg over the side.

“Whoa, now!” shouted the woman, warily. She held up her hands as if to calm down a crazy person.

Now I recognized the man. He was no longer wearing his Believe hat.

I lay back and faced the dazzling light pouring in. I arched my neck to take in the view. Sky! Through a ceiling!

The woman spoke. “How hurt are you? Is anything broken?”

“I’m okay,” I said, caught off guard. Had I really fallen through and landed directly, perfectly, ridiculously, in the middle of this queen-sized bed? What an idiotic, miraculous thing to happen. Catastrophe. Grace.

“Where do you live?” asked the woman. She was extremely pregnant, and impatient. Her hands were still up, a gesture of self-protection, or antagonism.

“Um,” I said. I twisted my head around on the pillow, trying to assess the dimensions of the room. I couldn’t see walls in the dim light.

I lifted my feet and tapped them together, checking to make sure they could do what I told them to. With my right arm, I patted my chest and then the top of my head. How long had I been lying here? Was time moving the same down here?

“I can’t believe Believe guy fell right onto the bed!” he said, and laughed. He couldn’t help it.

I laughed too. We both laughed.

Maybe they had placed the bed under the hole exactly for this reason—in case someone fell in.

I made myself glance down at my left arm. My hand was swollen. The part where I had hit the moth, on the outer ridge of the hand, was an upsetting shade of orange.

“It stung me,” I said, pointing with the good arm toward the bad.

“Who stung you?” the pregnant woman asked sharply.

“A moth. The invasive species.”

“They don’t sting. They’re harmless.” She said to the guy, “He hit himself with a hammer or something, didn’t he?”

“I guess so.”

“I told you to hire a professional. This is a liability,” she insisted. The man looked down. “Well, at least I don’t think he can sue.”

The woman came around the left side of the bed and leaned forward over me so that the tip of her nose and part of her forehead were in the beam of light. “Are you gonna sue us?” She placed a hand on her belly, in a gesture meant to rouse sympathy or obligation.

My left shoulder twinged. A tingling told me that the numbness was spreading into my chest.

“We should just take him back to the store where I found him,” the guy said.

“It’s not your fault, man,” I said without thinking, because it wasn’t his fault, although he had led me to his house and up the ladder and asked me to pretend to fix his roof with him. He was not the one who had smacked the moth. It occurred to me that there might be many more moths just like it up there, camouflaged on the shingles.

“But it is your fault,” the woman hissed at him. “You brought him here.”

I shrugged with one half of myself. I didn’t doubt it had been one of those moths. “Your roof is completely fucked,” I said. “You’ll never fix that.”

The woman sighed. “Obviously.”

“Yeah?” said the guy. “What do you know about construction?”

I gazed up at the sky again, through the jagged rupture in the roof, its split carapace. I was shrinking and beginning to rise effortlessly above the bed and toward the opening, then ascending through… surging out into the sky beyond… all the way up to level of the tree line… looking down at the house from above, taking in the broken roof… my vision increasing in contrast, light and dark inverting… my eyes bugging out sideways from my slim head and my antennae sensing the gentlest shift in air current… a protest, a sharpness within me, the bullet pushing itself out through my spine…

“Hey!” the woman cried.

I blinked my eyes. I found I was standing up, chin tilted back, eyes half-closed, bathed in light.

“Wait a minute!” she shouted. “Don’t go anywhere!”

Above us, a dark blotch flew in from the sky. A floater in my field of vision. It entered, or materialized, in the center of the rectangular hole in the ceiling, and lazily descended, zig-zag, taunting, downward, toward my nose, where it hovered, wings fluttering, a few inches above my face.

The others could see it too. We all watched the moth dart across the room, exploring. Eventually, it landed on the woman’s forearm. Its confident wings lifted and lowered, then stilled. It was the breadth and color of a roof shingle.

“Ew!” she said. “Get off!” She tried to shake the moth loose, but it was braced to her body.

“Don’t,” I said, but she didn’t hear or didn’t listen.

She raised her other hand high in the air, and brought it down.

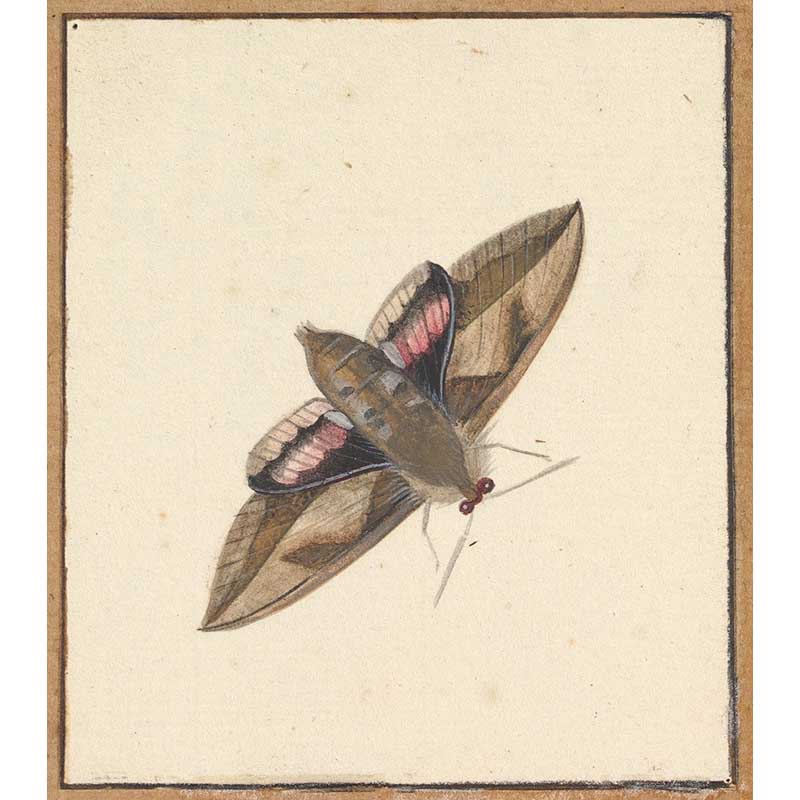

Nicolaas Struyk, A Moth, early- to mid-18th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Elvia Wilk is a writer and editor living in New York. She wrote the novel Oval (2019) and the essay collection Death by Landscape (2022), and a new novel, A Diagnosis, is coming in 2026. She is a contributing editor at e-flux Journal, and teaches MFA writing at Sarah Lawrence.

(view contributions by Elvia Wilk)