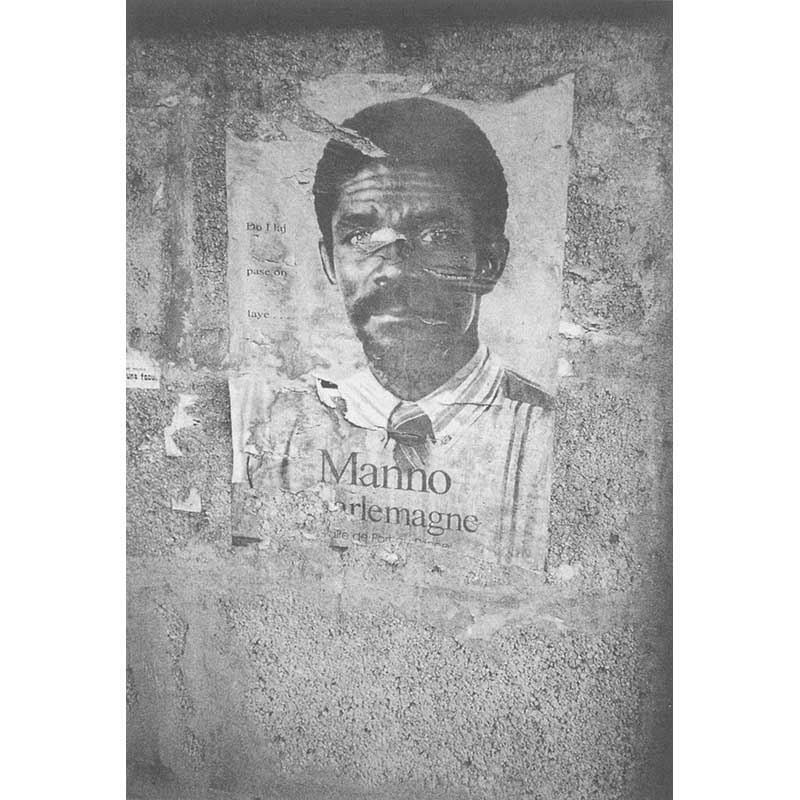

Campaign Poster, Port-au-Prince, 1995. Slogan reads: “His back is wider than a winnowing tray.” Photograph by Mark Dow.

Mardi Gras Man

I.

That grinning mask is the flag you carry—

That’s what your Mardi Gras has become.

Carnival hasn’t satisfied you yet,

And Ash Wednesday is almost here.

You take the country and you walk all over it,

You sell it for a nice house across the sea.

But I see through your Mardi Gras disguise—

Let’s see what happens if you lead the parade.

II.

As long as there are those who will take responsibility,

Who want to fight with lucidity,

I’ll open a white sheet for the honest ones—

Come lie in it, roll in it, confess your sins.

Don’t put the blame on underdevelopment,

Don’t look for words to hide behind.

Two centuries ago we were important people

Because we fought other people to make ourselves free.

(Refrain)

In Port-au-Prince you hear all kinds of things …

Mardi Gras Man’s parade float is an armored car.

Mardi Gras Man, I’m not afraid of you, you’re only a person.

It was the first time I saw how this works,

The Mardi Gras Man gives himself a military rank

To scare me, but it excites me—

Masked Man, I’m not afraid of you, I’m not afraid of you, I’m not afraid of you,

Masked Man, I’m not afraid of you, you’re only a person.

Smoke

I.

The one in hiding who takes wet leaves,

Pissed-in mattress-stuffing that’s not yet dry,

Is not making a fire to cook,

But to make us cough.

If you see tears running down our faces,

Our crying is not crying.

We are the conscience that stands up,

That moves on and analyzes

The puff of smoke that’s up to no good.

II.

The people have been initiated many times,

They’re through that place in just two or three steps.

On their land, they are the only king,

Little vodou priests like Lika,

Little Jan or Little Nikola,

Cannot make them march in step.

The people know what this means:

The life that is destroyed to give life

Can’t be lost, it will not be lost.

III.

The people know that the victory

Of respect for life and of right

Is something you have to fight for.

They know very well that you may die

If you just applaud and stand by,

No one has any doubt about that.

I don’t think the people were surprised

By what happened at midnight:

The day always follows the night.

(Refrain)

Smoke, listen closely.

Smoke, the mistress of the house is the one who gives the orders.

Smoke, don’t let the people get angry

Or they’ll open the door and, dammit, you’re gone.

My Brother

You would like me to sing yet again

the sweet song about the little birds to please you

even as I hear the cries of the dead

coming from our filthy prison cells

you’d like me to sing of the clear water

of the streams and rivers

of the Artibonite

red with the blood of our brothers

you call yourself a pacifist

you call yourself apolitical, my brother

You really like the romantic crooners

it pleases the beautiful women

who love to faint

it doesn’t hurt anyone

when the singer shakes it

in front of a clucking America

idols supply the thrills

which make us forget about the missiles

El Salvador and Haiti

Grenada and company, my brother

When show business makes big bucks

you’re no longer racist, my brother

you like rock, you like blues

you dance, you play at losing yourself

you wash your hands of it

you’re all good little citizens

and in the sand the ostriches

sleep the sleep of the just

while the great eagle plays

at devouring the weak ones

the weak ones, the weak ones, the weak ones

International Organizations

The international organizations are not for us;

They’re there to help the thieves plunder and devour.

When people who are suffering arm themselves,

Know that they are exhausted.

International medicine stays on the sidelines.

They hold meetings, they sit and they bullshit

With a glass of champagne, a nice imported wine

And that’s it.

When people are under the gun all over the world,

Don’t give me all that analysis

When you really don’t give a damn.

What people don’t want to hear

Is the truth.

Underdeveloped reactionaries are the most dangerous of all—

When their interests are threatened, they’re always the ones

Who call for intervention against the people who are rising up.

The dominant class is very clever:

In principle they know they are the minority,

They know how to play it,

Their class position is what counts.

They’ll do the impossible, they’ll rampage

To eliminate the child in the womb.

We will fight until the corn is ripe, until we are free.

We take heart from the struggles of other peoples who are not afraid to die.

Their deliverance is their efforts, is in their blood that is shed.

As for the pills the doctors would like to prescribe,

They throw them away.

We salute all peoples who are fighting,

We honor all those who have died

For the cause of freedom.

As for those Haitian dogs who say they are cultured

While making a living at their universities

From the suffering of refugees,

We spit in your face.

I Am in Misery

We are six million Haitians—

out of every hundred thousand, there’s one who lives well,

that makes six thousand who have money.

Is it God who wanted it that way?

You are the king as far as that answer’s concerned,

I don’t think it’s written in the Bible.

Ever since the old testament

slaves have always fought against kings,

they struggle to break their chains,

they fought against pharaoh.

You yourselves Haitian peasants,

who cannot read, that’s what they say,

one rice harvest isn’t two

and it isn’t three, but it is something.

Out of every five thousand intellectuals

four thousand nine hundred are full of shit,

a bunch of gutless, spineless pimps,

they forget that the people are the only power,

say a mass for the Americans to come in,

come take the country, thank you, sir.

Contraband plus charity

is for those with no face, it’s true,

with no honor, with no dignity.

It really is a pity

for a group of people who are cultured,

who went to school, who know their abc’s,

to bend their backs

with a beggar’s bowl wherever they go.

The angry river is trouble,

its union is with the sea,

for us that is clear.

For the man it’s pretty words,

especially when he wants to play a big role,

he’s a better singer than the nightingale.

He’s always talking about union,

when you see how he wants to be president,

comes down to the neighborhood in a nice car,

pays a couple of rara bands to play their bamboo horns,

brothers, don’t get scammed,

that’s what they call the big sham.

Let the thieves in Port-au-Prince

keep selling themselves for nothing.

(Refrain)

Six thousand people who have money—

in spite of all the old weapons

they find every time

we want to change that,

it doesn’t mean a damn thing

to the people

the day they want it to change.

I have to get out

of this misery I’m in,

neither tafia street parties

nor candidates can get me out of it.

To change this life,

to make an improvement,

it’s up to me to stand up and fight.

Note: Gage Averill provided extremely generous and invaluable contributions to all the translations.

Francine Chouinard co-wrote “Mon Frère.”

Rose-Anne Auguste co-wrote “Lan Malè M Ye.”

Manno Charlemagne participated in early versions of the English.

Gregg Ellis co-translated “Mon Frère.”

Thanks also to Rose-Anne Auguste, Karen Brown, Gina Cunningham, Peter Eves, Katherine Kean, Fresnel Laurent, Felix Morisseau-Leroy, Guy Nozin, Jan Sebon and Tap Tap.

—Mark Dow

NOTES ON THE SONGS

Gage Averill

Lamayòt: This song was written in 1989, the first year Carnival was held in Port-au-Prince after the fall of Duvalier in 1986. For three years, Carnival had been banned by the military authorities because it combines songs of political critique with exuberant lower-class crowds, an unstable mix for the elite in politically unstable periods. Lamayòt is an individual masque (i.e., not part of a large Carnival group). The Lamayòt carries a box in which he has hidden something odd, humorous, gross or obscene, and he charges people to look inside, or even to buy one of the contents. Parents will sometimes scare their children by telling them that the Lamayòt will put them in his box. The refrain “Madigra m pa pè w se moun ou ye” is also found in a 1960s Carnival song by Nemours Jean-Baptiste.

La Fimen: The line in the second stanza, “The people have been initiated many times,” literally says, “The people have undergone the fire ritual (kanzo) many times.” In a song in which Manno implies that the elite and army have lit a smoking (not burning) fire to blind and confuse people, the kanzo serves as a contrasting kind of fire, one that purifies and that tests people’s faith and determination.

When a gwo nèg (big shot) rides by in the street, the ti-nèg (little people) are supposed to line the street and bat bravo (pay collective tribute by applauding), as in the third stanza here. It is one of those many rituals of power that define hierarchy and the social order in Haiti.

Mon Frère: The Haitian term “twoubadou” (troubadour) includes singer-songwriters of conscience like Manno, but it also encompasses the quaint ensembles that play old méringues about the beauty of Haiti as well as Creole versions of Cuban trio songs. In the first stanza of this song, Manno contrasts himself to these quaint twoubadou ensembles. The song that he refers to in the second line is “Choucoune,” one of the best-known romantic méringues, with a chorus that starts “Ti-zwazo” (or Little Birds). This is the same song that is sung in English as “Yellow Bird.” In the second stanza, Manno tells us of another kind of singer that he isn’t: commercial singers in Haiti are routinely classified into “chanteurs de charm” (romantic crooners) and “chanteurs de choq” (hard rockers).

Oganizasyon Mondyal: The former dictatorship, in an effort to skim off more profits from the country, let foreign aid groups provide all of the infrastructure, health, education and agricultural development that the Haitian government should have been providing. The resulting foreign aid bureaucracy has been compared to a shadow government that too often works in the interests of the Haitian import-export elite and against those of the peasants and the poor. One translation of the title, “World Organization,” anticipates George Bush’s kinder, gentler “New World Order.”

Lan Malè M Ye: In the last stanza and the refrain, Manno tells Haitians not to be persuaded by the institution of the koudyay. Derived from the French phrase “coup de jaille” (spontaneous bursting-forth), the koudyay became a military celebration in Haiti, and eventually any street party “hosted” by an important person.

SELF-CRITICISM & SONG: A PROFILE OF MANNO CHARLEMAGNE

Mark Dow

When we were translating his song ”La Fimen,” Manno Charlemagne pointed out that he pronounces “minuit” in French, instead of the Haitian Creole “minwi”: “I pronounce it like a fucking bourgeois” in Port-au-Prince. He said he was just being honest about himself.

“Dear me, think of it! Niggers speaking French,” said Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan at the start of the first U.S. occupation of Haiti in 1915. Seventy years later, racist notions about Haitians and their language persist. Anthropologist Robert Lawless has documented two centuries of misconceptions about the Haitians’ “primitive language.” He notes that it should be called “Haitian,” not even “Haitian Creole.” The language, he tells us, is not a patois, and asks, “Would a journalist feel obliged to describe English as a mixture of Anglo and Saxon and Norman-French and some of almost every other European language?” Demeaning the Haitians’ language remains an element in the stereotypes that would dehumanize the people. As the United States began its second occupation, the New York Times referred to then President Aristide, who was also a priest, as “[t]he slight, left-wing Roman Catholic cleric with the Creole accent and exotic metaphors.” A CNN correspondent observed that while Aristide’s followers considered him also mystical, he had come to appear “almost European” in his dealings with Washington. It was only in 1987 that Haiti’s constitution recognized Creole as the country’s official language, and it is no accident that Creole literacy was a major element of President Aristide’s program. Government business has been conducted in French to maintain the division between the educated elite (what Lawless calls “a very small pseudobilingual ruling class”) and the illiterate majority. Aristide made history when he delivered his inaugural address in Haitian Creole.

Born in Port-au-Prince in 1948, Charlemagne spent his adolescence in the “popular” neighborhoods that would later vote overwhelmingly for Aristide and would, in return, suffer brutal military reprisals. When he recalls his childhood, Charlemagne describes the mix of politics, music and street language he absorbed in those neighborhoods. “I was raised in a lakou,” he says. “A lakou in the Haitian countryside means several houses that connect to each other. I lived in an ‘urban lakou‘ in Port-au-Prince. That means you have the Abel family, the Odé family, the Charlemagne family, etcetera. When Odé had a problem with my mother, I could hear them arguing. I could hear the dirty words they used. And I also learned from the workers, streetworkers, those macho guys who came from the countryside to Port-au-Prince. They are the ones who built the roads in Haiti. When they are digging, they are singing songs, dirty songs. So I was a specialist in dirty songs. I was the one who brought those songs to my school, helping rich kids who were raised behind high walls to know what was happening outside. I was their teacher. I was also singing church songs. I went to the Catholic schools, I was raised by the priests, so you might hear that Gregorian thing when I’m singing. Eight years old, six years, learning things from Jesus, from my school and from the street. I always prefer the street.”

Manno, as he is widely known—and his last name is “Chalmay” in Haitian—came to musical maturity in the “kilti libète,” or freedom culture, of the 1970s, described by Gage Averill: “The kilti libète groups’ choice of acoustic music set them apart from commercial, middle-class mini-djaz. Their model drew from a tradition of twoubadou (troubadour) music, a guitar-based tradition that owes a debt to Cuban sones and boleros as well as to older Haitian rural song traditions. In many cases, the groups rewrote and radicalized peasant songs, transforming them into weapons to use against the dictatorship.” In 1986, after the overthrow of Jean-Claude Duvalier’s dictatorship, Charlemagne returned from six years in exile and became an essential part of a cultural renaissance that included a rejuvenation of roots-based music. He was arrested twice after the 1991 coup d’etat that overthrew Aristide, Haiti’s first democratically elected president and a personal friend of Charlemagne. Finding refuge in the Argentine embassy in Port-au-Prince, Manno was able to leave Haiti with the help of former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark and a group of Hollywood stars led by director Jonathan Demme.

One morning last November, Port-au-Prince Mayor Joseph Emmanuel Charlemagne sat brooding about the assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. Charlemagne was sitting on the balcony of his room at the Hotel Oloffson, made famous by Graham Greene’s The Comedians. According to a story that may be apocryphal, when Charlemagne returned to Haiti in 1994 after the three-year coup, he found that people with nowhere else to live had moved into his Port-au-Prince home—and had now put up a banner welcoming him back. Since they had nowhere else to go, according to the story, Charlemagne let them stay, and he moved into the hotel.

As Charlemagne spoke about the Rabin assassination, it became clear that his mind was not on the intricacies of Middle East politics. And he was certainly not participating in the grotesque public transformation of Rabin into a martyr for peace. On the contrary, Charlemagne instinctively understood that Rabin’s “peace agreements” were simply a strategy change from the days of breaking young Palestinians’ bones. The 1986 song “Oganizasyon Mondyal” (International Organizations) is a clear indictment of international “aid” in Haiti. And it was appropriate to translate it, as we did, for a September 1994 concert in Miami Beach denouncing the second U.S. occupation of Haiti. But Charlemagne wrote the song in the aftermath of the massacre of Palestinians at Sabra and Shatilla in southern Lebanon. “I saw [United Nations Secretary General] Javier Peres de Cuellar think, by drinking a glass of wine with King Hussein of Jordan, he can resolve that problem,” Charlemagne said. Then, alluding to the so-called “peace process” under way since the secret Oslo agreements, Charlemagne added, “Now, what happened? See, I was right.”

But Charlemagne was thinking of the Rabin assassination in a larger context: in his next breath he lamented the growing strength of reactionaries in France. He was upset, at the most personal level, by the increasing power of the right in all its forms. And, in his new position as mayor, he was also worried about Haiti, and about himself. Over the next few days, the phones kept ringing, and many of the calls brought unconfirmed reports of killings in various parts of Haiti—the kinds of killings that made Charlemagne and other activists fearful about a growing boldness by anti-democratic forces, and the kinds of killings that would not be important enough for the media to cover. For now, the media wasn’t in Haiti. Why should they be? On the one hand, there weren’t photo-op bodies on the streets within a short distance of the main Port-au-Prince hotels. And on the other hand, the State Department wasn’t saying that there was news.

Within days, Charlemagne’s foreboding proved justified. The police discovered a large weapons cache in the Port-au-Prince home of former dictator Lt. General Prosper Avril. Avril himself escaped to the safety of the Columbian embassy—”right over there,” Charlemagne gestured from his balcony railing. He seemed in those few words to be outraged, disgusted and afraid. And obsessed: he wanted to get Avril, he wanted to speak with an American attorney and friend due in town any day about how to get Avril. When the attorney showed up and said, “How are you?” the mayor replied, “I’m fighting.” The Avril situation wasn’t the only danger, but it was emblematic. About a week later, the mayor and some of his staff and security people were working late at the Hotel de Ville, or city hall. Gunmen appeared and opened fire on the building with automatic weapons. Charlemagne said later that this was meant to scare him, not to kill him. He also said that he saw National Police and U.N. vehicles (which would have been under U.S. command) drive by and keep on going.

That same week brought the assassination of Jean-Hubert Feuille, deputy of Parliament and a cousin and close ally of Aristide. Some interpreted this as a clear warning to those who would continue efforts at economic and social reforms. At his cousin’s funeral, Aristide delivered a powerful, angry eulogy in which he demanded that disarmament be enacted in earnest, “total et legal,” not just in the slums but in the big houses of the wealthy. And he encouraged the people to work with the new police force to expose hidden arms. The North American press finally found news in Haiti: Aristide’s speech was thoroughly misrepresented as a call for violence from his supporters. His indictment of the international community for failing to disarm supporters of the military was not taken seriously.

It is important to remember that the occupying American forces had made a lot of noise about disarmament without doing much disarming. And that also should not be surprising. The United States has supported the military and paramilitary repression of democracy in Haiti since it first occupied the country early this century (1915-1934) and created an army designed to repress its own citizens. More recently, the U.S. had actively opposed Aristide’s presidential candidacy, opposed his populist efforts at reform during his seven months in office (creating a front organization, for example, to work with the Haitian business community in opposing Aristide’s efforts to raise the minimum wage) and continued to work secretly with the Haitian military—and train them—during the charade of Washington-brokered negotiations to return Aristide to office. Moreover, as journalist Allan Nairn has documented in detail, the U.S. financed the paramilitary organization FRAPH during Aristide’s exile as a counterweight to Aristide’s supporters in Haiti. FRAPH is responsible for thousands of cases of rape, torture and murder of Aristide supporters. And as Nairn also discovered, U.S. defense personnel were inside Haitian military headquarters when the coup against Aristide took place on the night of September 29, 1991.

Manno’s ”La Fimen” (Smoke), the title cut on his most recent album (1994), is about that koudeta (coup d’etat). He told me that his intention in this song—which he admits is “a beautiful song, which took me some time to write”—is not only “to accuse the army . . . to accuse [the one] who tries to do something in secret,” but also to “minimize the idea of the coup.” It is this second intention, I think, which is the perfect example of the kind of independent thinking that angers many of Manno’s potential (and former) political allies, and which also points to the sense of complexity that makes so many of his songs into poems rather than political tracts set to music. A few years ago, a Haitian newspaper editor said that Charlemagne “does not make metaphors. If he sees a murder, he calls the man a murderer.” The editor was right about the directness, but wrong about the poetry. “M pa kwè la pèsonn sezi/Pou sa k te rive a minui/Se nuit ki ale jou pral vini”: “I don’t think the people were surprised/By what happened at midnight/ It’s night that goes, day is coming.” In these lines Manno is minimizing the idea of the coup, not only by saying no one was surprised (as no one is surprised that day follows night) but by offering hope for change (night gives way to day) in the same image.

“This was the very prototype of the Chilean coup,” Manno told me in August 1994. “The difference is that in Chile the U.S. used generals, and in Haiti they used the majors. The U.S. had used majors in the Haitian army to eliminate people when there was a danger of a popular uprising against Avril when Avril was in Taipei [in 1990]. The majors still control the country today. So they trained those majors, and then saved them for something interesting—they used them to overthrow Aristide.” In the song Charlemagne says no one was surprised by the coup, but he has said in an interview that the progressive community let down its guard and allowed itself to be victimized: “People saw the election of Aristide as an end instead of a beginning. For the first time the progressiste community in Haiti had the power, and we were drugged. After working so hard to overthrow Duvalier, the movement started to become weak. When Aristide took power, people were resting. . . . They thought the fight was over after February 7, 1991 [Aristide’s inauguration]. And the coup happened.” If all this detail seems a bit esoteric, that’s only because it is unfamiliar. There is nothing inherently mysterious about these political machinations, in spite of North American journalists’ propensity for the word “murky” when reporting Haitian politics. Certainly there are complications and intricacies, but they are made murky by the press’s complicity with U.S. propaganda about its role in the world. Because of our grade-school indoctrination, there are things we can’t easily see that the illiterate Haitians know as a matter of life and death:

Si ayiti pa forè

Ou jwenn tout bèt ladann 1

Ou jwenn lyon, ou jwenn tig

Ou jwenn chat, ou jwenn rat

Ou jwenn menm leyopa

“If Haiti is not a forest/you still find all kinds of creatures there./ You find lions, you find tigers/You find cats, you find rats/You even find leopards.” This list of animals isn’t about some Serpent and the Rainbow melodrama, which we have been conditioned to associate with Haiti. In a song combining his own lyrics from 1974 with a 1986 resistance song from the town of Gonaïves against Baby Doc Duvalier and his wife, Michelle Bennet, Charlemagne is singing about the U.S. role, which we have been conditioned not to be aware of. The Leopards were an elite, U.S.-trained battalion in the Haitian army:

Ki leyopa souple?

Yon bann fòv malmaske

Si gen nenpòt ti bwi

Ti bwi tankou latòti

Leyopa pran kouri, wi.

Which leopards, please?

A bunch of thinly disguised beasts.

If there’s any little noise,

even the noise of a tortoise,

the leopards run away, yes.

Here two crucial Charlemagne strains come together: the constant effort to unmask the hidden perpetrators, the hidden realities and the victory over fear that comes with the unmasking. These songs call for resistance, but they also demand and offer analysis. In “Ayiti Pa Forè” he also sings, “M pat gen bon pwofesè/Ki pou te montre m koulè/Ki pou te ka fè m wè klè”: “I didn’t have good teachers/To show me the colors/To make me see clearly.” Elsewhere he sings sarcastically, “Banm yon ti limyè, mèt/Banm yon ti limyè pou m wè sa k ap pase”: “Give me a little light, boss/Give me a little light so I can see what’s happening.” He could have been singing to the New York Times‘s Rick Bragg, who “explained” the relations between Haiti’s wealthy elite and the military on the eve of the occupation and noted, “Poor Haitians cannot understand all this.”

“Lamayòt” in the present selection of songs is an excellent example of seeing through masks and overcoming fear. Here Avril enters the picture again. Manno wrote the song in exile (in Boston) in October 1989, just before the November arrests by Avril of activists Evans Paul, Jean Auguste Mezieu and Marineau Etienne. These men were tortured by the Avril regime and then put on Haitian television as a gruesome warning, and they became known as the “Prisoners of All Saints’ Day.” Manno describes the refrain of the song as introspective; he’s thinking over what he has seen. I use the ellipsis in the line “In Port-au-Prince you hear all kinds of things . . . ” to try to give a sense of this contemplation. And I should note here something that is applicable throughout these transcribed versions: these are songs, and when Manno sings them, his melodies and his guitar and his voice are hauntingly beautiful.

What I hear in his voice is crucial to my reading. “Madigra bay tèt li on grad souple/Pou’l fè’m pè se lè sa-a’m pral pyafe/Lamayòt m pa pè-w m pa pè-w m pa pè-w/Lamayòt m pa pè-w se moun ou ye”: “The Mardi Gras man gives himself a military rank/To scare me, but it excites me—/Lamayòt, I’m not afraid of you, I’m not afraid of you, I’m not afraid of you/Lamayòt, I’m not afraid of you, you’re only a person.” In an earlier version, I omitted the repetitions, thinking they were unnecessary on paper. Then I listened to the song again (it’s also on the album La Fimen), and felt the repetitions were essential to the mood, the singer explaining things to himself, seeing them for what they are, and then as both warrior and child, getting excited at what is meant to scare him, repeating the phrase to calm himself, and also to prod himself into battle. Manno once told me: “I was raised by my aunt, not my mother. And both of them are singers. I didn’t know who my father was until I was thirty-seven years old, and it turns out that when I knew my father’s family, they’re all musicians, too. And I feel I had some psychological problems because of not knowing my father, some ‘child problems.’ If you listen to my songs, you can feel it.” In ”Lamayòt” you can feel it.

On a more explicit level, too, ”Lamayòt” is about self-criticism, what Manno in his richly imperfect English calls “auto-critic.” Of the line, “Don’t put the blame on [the word] ‘underdevelopment,’” Manno says he is “talking with my fellow leftists.” The false nationalism of the abused flag in the opening line becomes the white sheet in the second stanza, which Manno offers to those who want to “fight with lucidity”; I rendered “montre salte,” literally “show [your] dirt” or “dirtiness” as “confess your sins.” Manno approved: the Bible says wash your sins, he said, in my language it means come and make your auto-critic. After he wrote the song for Evans Paul and the others, Manno says, he discovered that they weren’t so clean after all. In the margins of his transcription of the song, he listed Paul and others who he claims were involved in meetings with senior U.S. officials leading up to the 1991 coup. “And I wrote the song for that fucker,” he said. Paul was the mayor of Port-au-Prince when Aristide was overthrown, and after Aristide’s return, many observers felt Paul was being groomed by the United States to succeed him. He was running for reelection to the mayor’s office when Manno decided to enter the race in the summer of 1995. (Paul has also been a playwright and founded a Port-au-Prince theatre company in the eighties; he is commonly known as K-Plim, an abbreviation for “literary sage.”)

I’m not at all sure that the personal/political animosity is what made Manno decide to run. So what did? When I asked him, he didn’t really answer. He said that when he saw his pictures on walls around the capital, he realized that it was for real. But then he tells me that he paid for those posters himself. He also said, “I’m a student man,” meaning that his activist work had long been with students, and that students had pushed him to enter the race. Finally, he tells me a joke that had aired on the radio about the candidates’ campaign slogans. For Paul: he’s the incumbent. For Frank Romain (Port-au-Prince mayor under Baby Doc): he’s a makout (or Tanton Macoute). For Manno Charlemagne: “Pourquoi pas?”

Graffiti also appeared on Port-au-Prince walls during the campaign saying “Manno Charlemagne li pwòp”: he’s clean. Self-criticism is a cleansing rite, and Manno will often indicate his approval for someone by saying “He’s clean.” Before the return of Aristide, Manno was frustrated with the exile community’s obsession with returning him. He felt that negotiations with Washington could not ultimately benefit Haiti, and he made enemies among former supporters when he said on Haitian radio in Miami that Aristide would not return. Explaining himself later, he said, “[The people] have to know, Aristide was their man. There can be others, there can be, there will be someone else, some other person, clean person, to help guide the movement.”

Rose-Anne Auguste was with the student organization FENEH when she co-wrote “Lan Male M Ye” with Manno in 1987, on the eve of elections which the U.S.-sponsored military stopped with an election-day massacre. Auguste operates a community health clinic in Karfou Fey, one of the “popular neighborhoods” or slums of Port-au-Prince, which were Aristide strongholds. She courageously opened the clinic during the coup years, and since the U.S. occupation has refused to accept funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development. When I spoke with her on the balcony of the clinic, patients waited below, under a gazebo, watching a video about AIDS prevention prepared by Paul Farmer (Farmer, author of the indispensable The Uses of Haiti, is an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard and runs a clinic in rural Haiti). Auguste told me that she respects Manna’s strategy though she disagreed with his decision to run for office with the country under occupation. “Se nèg ki renmen batay,” she said. “He’s a man who loves to fight.” “Yo pa ka achte 1 fasilman,” she added. “They can’t buy him easily,” and that is why the job is dangerous.

In fact, back in November, Manno could not stop talking about those in the government whom he accused of buying or being bought. He talked to anyone who would listen about the ”vòlè,” the thieves, just as he has in his songs for years. Now, in the opinion of one longtime Haitian activist and former political prisoner, Manno was incensed because he was seeing up close what he had known about for years. Manno often drives himself around the city, and when pedestrians recognize him at a stoplight or stuck in traffic, they start to gather around the car. Again and again I saw Manno respond by rolling down the windows to talk to people. Sometimes he asked them what they wanted. Other times he just started in with whatever was on his own mind, and often that was the vòlè. He went on the radio to denounce particular people in the National Palace, that is, in the Aristide government, who were profiting from drug trafficking or who had unexplained large bank accounts of U.S. dollars, and he criticized Aristide himself for knowing about these people and tolerating them. One person told me she felt Manno was brave and doing the right thing, another felt he was making a mistake by lashing out instead of organizing. But he could not help himself.

At the National Palace for the swearing-in of a new prime minister, Manno said he felt like “une mouche dans ver du lait,” a fly in a glass of milk. He seemed physically uncomfortable in his suit, among the dignitaries of whom he was now one. Last night, he tells me, playing music at the Oloffson, I was relaxed. Here I have to shake hands with people I hate. I can’t keep doing this—”I’m a natural guy.” In the same week he told me, “I’m starting to enjoy this job” and also that he felt “morally tired.” At his office downtown, he can spend a whole day without sitting at his desk, moving from one constituent to another. They were coming to see him personally. “You see that guy,” he says of a young man, maybe eighteen, “he should go to school … ” Another young man talks to the majistra about getting materials for a construction job. “He’s the best carpenter around,” says the mayor. An old man outside wonders when he will be paid—he’s been sweeping the streets since the former mayor’s office hired him, and he hasn’t been paid in four months. The current mayor is obviously embarrassed by the indignity of the situation. “I know that guy since I was a little kid,” he says. And of a woman who has come asking for money for a prescription, he explains, “Her son is dying from malaria.”

But that is not the whole picture. In April, a major human rights organization in Haiti condemned the mayor’s office for its agents’ use of violence in clearing ti marchand or small vendors, mostly women, from their longstanding but illegal spots on the streets and sidewalks of the capitol. The group compared the arbitrary use of violence and authority to FRAPH tactics. The next month, the mayor announced that, because the new police are incompetent, he would arm his own people to patrol the city; the Interior Ministry said that such a force would be unconstitutional.

In a characteristic blend of ego and humility, Manno Charlemagne once told an interviewer, “I’m not supreme. There are a lot of people they say came from heaven and dropped to earth. I am the child of a woman, a poor woman who suffered but who felt the necessity for me to help others.” One hopes that in the pressure of the current situation, Manna’s respect for democracy, complexity and self-criticism will prevail.

Manno Charlemagne (1948-2017) was the mayor of Port-au-Prince and Haiti’s best known singer/songwriter. His albums include Manno et Marco, Fini les Colonies and La Fimen.

(view contributions by Manno Charlemagne)Gage Averill provided the notes to Mark Dow’s translation of Five Songs by Manno Charlemagne.

(view contributions by Gage Averill)